Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPaul Gauguin

The Father of Post-Impressionism

STEPHEN HAWEIS

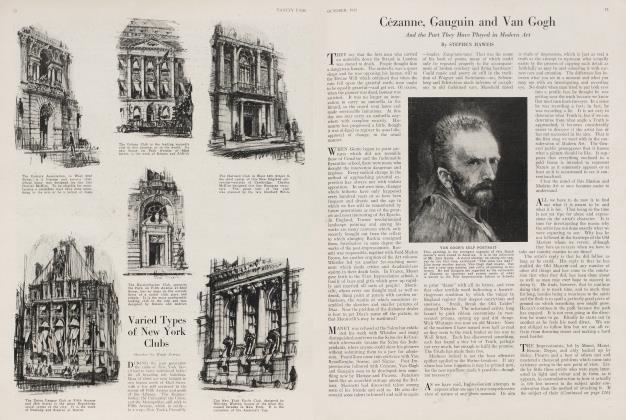

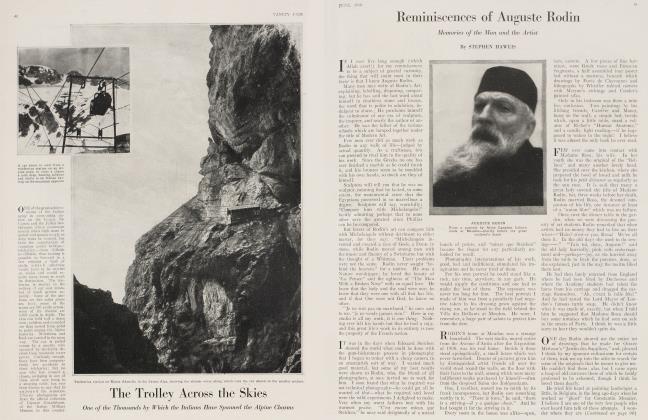

THERE is a melancholy charm about gleaning in the field of a great man's life. When the harvest of a genius has been reaped and garnered there must always be much that is forgotten, but it is our duty to gather up as many of the "fragments that remain, that nothing be lost." Any trivial detail may perchance throw light upon the character which was at once the cause and result of that great man's work and worth.

Paul Gauguin was a great man. Future generations will decide the magnitude of his star, but that it will remain alight in the firmament of Art, there are now few to deny. The gentle, insulting principle of "de mortuis nil nisi bonum" has robbed Humanity of much that History might have afforded.

Biography contrives too often to create a lifeless idol for succeeding generations to worship, in which we can hardly recognize ourselves at all. It is certain that Gauguin lived not as strict moralitarians think right. He is said, also, to have been addicted to morphine and alcohol, and it is sure that what he desired, he always found means to attain. But one day Gauguin, who left Tahiti for the Marquesas Islands in 1903, gave to the captain of an American ship his case of needles and hypodermic syringe. He succeeded in renouncing morphine, when it had already become a habit.

IT is pleasing to know that in the closing years of his life he was not in want, as he had been in earlier days. He sent his work to Vollard's in Paris regularly and was enabled thereby to draw from Maxwell & Co., Papeete, all the money he required. Poverty had not made him miserly. He gave freely to the natives whose cause he made his own. Unnumbered acts of kindness and generosity are remembered about him in his latter days, so that his memory remains green in the hearts of a people in whom by nature there is little more than the undeveloped bud of gratitude.

It has been my fortune to meet a French Protestant missionary who knew Paul Gauguin well, who spoke with him on the morning of his death and came to his bedside in the evening while the body of the master was still warm; although differing from him on many points of religion and philosophy, he was able to say that, if his practice and example were often deplorable, his influence was on the whole helpful and desirable for those among whom he lived. Gauguin was a rabid antagonist of religion, but he was able to separate the man from the priest among his friends, so that the missionary avowed that the master was a charming man, a fascinating talker with a profound knowledge of Art and Literature. Gauguin read a great deal. He admired Flaubert, De Maupassant, Mallarme, and owned many books containing dedications by their authors, which show that he had personal and even intimate relations with some of the most brilliant men of his day.

Continued on page 108

Continued, from page 106

ON his arrival at Atuana in the island of Hivaoa, where he lived in the Marquesas, he was at first on good I terms with the local Catholic Bishop, —just so long, I fear, as was necessary to obtain from him what he required, namely, a certain piece of land for which he paid about eighteen hundred francs, by no means less than its value. Upon this land he built his house, now destroyed, though the frangipanni or "temple trees" that he planted with his own hand at the corners of it, remain, together with the bathing tank which he made for swimming. Frangipanni blossoms are the funeral flowers of Tahiti.

The house he made was long and narrow, set upon piles two metres high. Beneath the house was the kitchen, where he also kept the carriage that he brought from Tahiti. It was quite useless here as there were no roads upon which to drive, nevertheless he was" not content to have it seized for non-payment of taxes. In a letter to M. Brault, his lawyer, he says: "I had written to the Governor that not having any legal means of protesting, I will not pay my taxes, 24 francs and costs, until our customs duties are included in our budget. I have just been distrained upon for this sum and here is a list of the things they have taken as an equivalent; a horse, a new carriage, a sporting gun and . . . four statues of sculptured rosewood!"

He explains further that he had plenty of other movables which might have been taken, but the fact' is that Gauguin had made himself distinctly unpopular with the Powers by at once plunging into politics and taking the natives' part against the police.

The house was entered by a flight of stairs at one end and at the foot of them were two carved posts representing, respectively, Le Pere Paillard, a frank caricature of the bishop, and Sainte Thérèse. Upon the walls, also, there were two carved panels. The one on the left bore the legend, "La Maison de Jouir," and on the right, "Soyez mysterieuses et vous serez heureusesl"

UPON a pedestal before the door stood a sculpture of wood made after the manner of the old native idols, upon the front of which he wrote:

"Les Dieux sont morts

Atuana se meurt de leur mort."

That is the key of his feeling with regard to the native life of the islands. He soon came to blows with the Catholic Bishop and openly ridiculed both him and his tenets. He constituted himself a buffer between the natives and the unscrupulous police who were, at that time, an omnipotent nuisance in the islands.

He frequently came forward to save unfortunates from their clutches, and there is little doubt that his last conflict with the authorities was the direct cause of his death.

"Some natives have just been convicted for having accepted soap upon which duty had not been paid," he wrote, "instead of money for their work on certain whale boats. It would seem that it was the seller (the whaler) who is the one at fault, especially the captains, as some sailors who deserted have affirmed that they went away very pleased, and that the policeman had had his palm greased a little. Naturally, the policeman has his accounts in perfect order, having all the bills of lading and declarations for the customs.

Nevertheless, these poor natives do not understand that the policeman himself bought a number of goods on his own self-authorization alone. A fine baby carriage which was lent to him has been left behind, by mistake, which explains there being no bill of lading for it."

Gauguin accused this policeman with whom he was continually at war of corruption, and of introducing the baby carriage into the island without paying duty on it.

AUGUIN was convicted of libel and defamation of character. He was condemned not only to a fine, but also to a term of imprisonment by the local magistrate, and the shock of this judgment contributed much, no doubt, to create the clot in the heart which killed him.

The Church forgives and forgets all. Hardly was the breath out of his body than the Bishop, "Le Pere Paillard," made his appearance in the House of Joy to bless and perform those ceremonies which Gauguin so heartily despised. The funeral was fixed for the following morning at eight o'clock, but lest the Protestant missionary or other personal friends of the master should raise objections, the body was quickly removed and buried an hour earlier in Holy Catholic ground,—and so it remains.

THE policeman; too, whom Gauguin hated so bitterly was not absolutely idle. He hurried round to the artist's house and there discovered a walkingstick, carved by Gauguin, which did not meet with his approval; it was in his opinion detrimental to public morals in Atuana, so he seized and destroyed it. "Nevertheless, it was a work of Art," said the missionary, "and should have been respected as such. Gauguin's house was not one to which one could take a 'jeune fille.' He did many things as an artist, no doubt, that were not for the general public, but he was never morbid or unhealthy minded. He was 'un charmant homme!"

Besides his only published book, "Noa Noa," (Perfume), Gauguin certainly possessed two other bulky manuscripts to which he added from time to time. One of these was called "Conseils a Ma Fille", full of wit and satire, together with other matter most parents would consider very undesirable for daughters. The other was a "sort of philosophy of religion," expressed in a criticism of the four Gospels upon which he spent a good deal of time. This manuscript was bought at his sale by his old friend, Dr. Chassagnol, and given by him recently to Madame Géraud among a number of other relics and sketch books. "Conseils a Ma Fille" may be among those also, but I believe them to have been lost.

ANOTHER incident pleasant to remember is recorded in the form of a deed of gift said to be filed somewhere in Papeete. Adjoining Gauguin's land was another property owned by a Marquesan native named Tioka. About half of this property was engulfed and swept away one day by a tidal wave. Gauguin at once gave Tioka half of the best part of his own land, and made a formal deed of gift, so that no one should afterwards be able to dispute it. If he was not a good Christian, there were times when he behaved like one, even in missionary eyes.

At his death all his effects, "his house and all it contained," were transported to Papeete and sold by auction, where some of his pictures sold for small sums, and the remainder were raffled for with two-franc tickets 1

There are many sore heads among the local business men who saw that sale and realize too late that a great fortune was well within their grasp.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now