Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe True Swordfish and Its Capture

The Story of the World's Most Gamy Game-fish

W. C. BOSCHEN

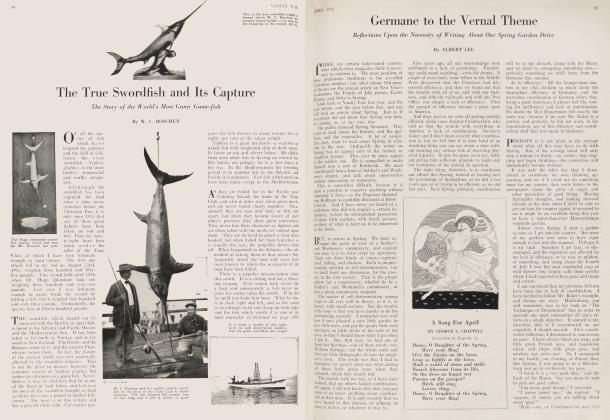

OF all the species of fish which have tempted the patience and the skill of fishermen, the true swordfish— Xiphias gladius—is the most tireless, resourceful and worthy antagonist. Although the swordfish has been captured for food since a time many centuries before the Christian Era, it is only since 1913 that any of these giant fighters have been taken on rod and reel. Thus far, twenty-eight have been taken under the rules of the Tuna Club, of which I have been fortunate enough to land eleven. The first one which fell to my rod on August 22nd, 1913, weighed three hundred and fiftyfive pounds. This record held until 1916 when Mr. Hugo Johnstone took one weighing three hundred and sixty-two pounds. Last year I was fortunate enough to again break the record by killing a fish which weighed four hundred and sixty-three pounds. Undoubtedly, the species runs to fifteen hundred pounds.

THE swordfish, which should not be confused with the Marlin, or spear fish, is found in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and the Mediterranean Sea. It has been taken as far north as Norway and as far south as New Zealand. The Greeks and the Romans wrote of it, and the ancient Phoenicians before them. In fact, the history of the ancient world was very materially affected by the swordfish fisheries. This is not the place to discuss, however, the economic aspects of A iphias gladius, but rather his attributes as a game fish. Nevertheless, it may be said here that he is one of the finest of food fishes, and last year the meat of the swordfish brought as high as thirty-five cents a pound to market fishermen. The meat is of fine texture and has a grayish white color. For market purposes the fish dresses to about seventy-five or eighty per cent of the taken weight.

Xiphias is a giant mackerel—a scaleless or naked fish with roughened skin of dark metallic lustre on top and silvery below. He differs from most other fish in having no ventral fin. His habits are pelagic; he is a free-lance of the sea. In the Alediterranean the breeding period is in summer but in the Atlantic and Pacific it is unknown. Few fish with known roe have been taken except in the Alediterranean.

AS they are fished for in the Pacific near Catalina Island, the home of the Tuna Club, and also in other seas, these great mackerel are never found closely together. Occasionally they are seen only forty or fifty feet apart, but when they become aware of each other's presence they show great uneasiness. They never lose their character as fighters and are often taken with the marks of combat upon them. They are inclined to attack a boat when hooked, but when fished for from launches, as is usually the case, the propeller drives them off. When harpooned in the Atlantic—the sole method of taking them in that ocean—they frequently attack the boat and cases have been known in which the occupants of the boat have been killed.

There is a popular misconception about this sword. It is a cutting and not a thrusting weapon. Fish cannot back water like a boat and consequently a fish never impales his enemy upon the sword. If he did he could not shake him loose. What he does is to slash right and left, and as the sword is exceedingly hard and sharp on both edges and the fish which wields it is one of the most muscular creatures known to natural history, it is not difficult to realize how dangerous a weapon it can be.

(Continued on page 106)

(Continued from page 54)

TT is the most muscular fish known and it is practically tireless. I have fought a swordfish for from ten to eleven hours and then found him as fresh at the finish as at the beginning of the battle. The fish jumps from the water very frequently without any apparent cause. I have known one to jump fifteen times in rapid succession. They can jump as far as thirty feet and as much as fifteen feet from the water. The splash can be seen five miles away. Indeed, it is this splashing which often reveals the presence of his prey to the fisherman. Sometimes, when hooked, a series of wild jumps are the first move which the fish makes in his battle for freedom. One has been known to jump twelve times when hooked.

The swordfish is a cool and scientific fighter, however. He seems almost to exercise human thought. He saves his strength and uses all kinds of methods of combat. He will fight on the surface for several hours and then suddenly submerge and fight for hours at varying depths up to a thousand feet, endeavoring frequently to work under the boat. After seven or eight hours of constant struggle you may think that he is whipped, but in a flash he will resume the fight and more often than not, get away, taking most of your tackle with him. It frequently occurs that this new lease of life or second wind seems to come to him at the blow of the gaff. He has been known to tear the gaff through eighteen inches of solid meat. His vitality is enormous and I have seen fish apparently dead and lying on the deck, react convulsively to a touch, four hours after taking.

THE best resources of a fisherman are taxed to overcome an antagonist of this calibre, especially under the strict rules of the Tuna Club. By these rules, a fisherman is limited to the use of a twenty-four thread line which may not have a breaking strain of more than two pounds to the thread. The rod must be of wood and the tip, when seated, not less than five feet long and weighing not more than sixteen ounces. The total length of the rod may not be less than six feet six inches, and the wire leader to which the hook is attached may not exceed fifteen feet in length. The angler is allowed to double back his line where it is connected to the leader, for only fifteen feet. Usually about fifteen hundred feet of line is used on a number 9/0 reel.

The swordfish is taken in the Mediterranean sea by means of harpoon and also of nets. A peculiar form of the latter which is the favorite one, is called the "Palamitara." Necessarily, in some instances, the fishing by net is done at night and in this case the net, which may be as much as 2,500 feet in length and made of very heavy twine, is set with a buoy at each end. This buoy has a bell attached and the fishermen lie off in their skiffs, waiting for the signal. When the bell rings they know that the old gladiator is there and in trouble. They hasten to the net forthwith, kill the fish, remove him from the net, and prepare it for the next victim, with many invocations to their patron saint, and cabalistic passes for good luck.

The "Palamitara" is a very baggy net and when the fish encounters it, he is soon entangled in its loose folds. The fiercer his struggles the more firmly he is held. For this reason this form of net is particularly well adapted to ensnare so belligerent a fish as the swordfish.

The habits of this warlike game fish are odd. He is very fond of surfacing in warm, calm weather. He is always moving. As the breeze freshens, The fish increases his speed and begins to hunt. One of the fascinations of this sport is that you can see the fish from three to five miles away. His dorsal fin and the upper lobe of his tail— sickle shaped—rising from the water, are frequently mistaken, especially if the fish is a large one, for a schooner. Of course these fins are not really as large as the sails of a vessel, but because of mirage conditions they seem so when seen from a small boat.

HEN the fish see the bait, and they can see it from a distance of from five to seven hundred feet, they sink and—it seems in a fraction of a second —grab it. They are the speediest that swim and can make from ninety to one hundred miles an hour for short distances. Sometimes the fish do not seem at all hungry and will then play with the bait or pay no attention to it. Again they will take the bait with a ferocity which is astounding. Various fish are used as bait and the whim of the swordfish must be suited exactly. At times they will accept nothing but a large bait, weighing twenty to twenty, five pounds, such as an Albacore. Again, they are tempted by a flying fish weighing only a pound and a half or so, and I have known times when they will take nothing but a small smelt weighing perhaps one-third of a pound.

MUCH of the success of the battle depends upon the way in which the fish is hooked. When simply hooked in the gristle of the mouth, no loss of blood ensues and, consequently, the fish does not weaken. In such cases the chances of taking him are rather slim. Should the hook be lodged in the gills, however, which correspond, of course, to the lungs of a warm-blooded animal, or, as is frequently the case, should the hook be deeply swallowed, there is then much bleeding and the fish, weakens very much more rapidly. It is in such cases that the angler stands a reasonable chance of success. But one never can tell. Constant surprises are in store for the disciple of Isaac Walton who chooses the swordfish for his quarry.

A friend of mine hooked one, as he thought, in a very favorable way. He fought him for four hours and thought he was tiring rapidly. At the end of five hours he was certain that he was tired, but at the expiration of five hours and fifty-five minutes, Mr. Swordfish spied a school of bait and decided that it was time for him to eat, which he promptly proceeded to do, breaking my friend's line and disgusting him at the same time. Fish have been taken, however, in half an hour chiefly owing to the fact that the hook was fast in a vital part.

TN taking my record fish of last summer I only had to fight about two and a half hours. My boatman and I didn't realize how large a one we had hooked at first and indeed it was not until we got him alongside and safely gaffed that we found what a giant he was. We could not get him on board the launch, although we had always been able to do this with other fish, and we were forced to tow him nine miles into the dock of the Tuna Club.

If anyone wants to have excitement of the highest order, lasting from the moment that the fish is seen until he either escapes or is killed—which may be a period of anything from an hour to eleven or twelve hours—let him try his hand in the waters of the blue Pacific near Catalina Island. He will readily acknowledge after a little actual experience, that Xiphias gladius is the most worthy antagonist among the game fishes of the world.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now