Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Spanish Invasion

New York Is Now Occupied by an Army of Iberian Musicians

PITTS SANBORN

TO us, in the United States—and the same thing has been true in France, England, Italy, and elsewhere—Spanish music was long summed up by the name, "Carmen" —the title of a French opera by a French composer.

In a "Carmen" performance we saw Spain—the gypsy girl, wearing her shawl, smoking wickedly, engaged in the ancient pursuit of enmeshing soldiers; the toreador of the moment armed with an all-conquering song, the outside of a bull ring, cigarette girls, ragamuffins a la Murillo, dancers, and smugglers.

In the streets and taverns of Seville, in the secret places of the mountains, we saw unfolded a gripping drama of passion, boredom, jealousy, revenge, and Fate. This, to us, was Spain. This, to us, was Spanish music.

I have no intention of disparaging the music of "Carmen," an opera which, after three and forty years, has lost not a whit the sharpness of its appeal to us. But I must point out that an opera which, decades ago, won over France, England, the United States, Germany, Italy, and Russia, has never, in Spain, been esteemed so highly. The fact is that the Spaniards knew that the music of "Carmen" was not Spanish.

Spanish dance rhythms, in three or four pieces; one authentic Spanish tune (the "Habanera" of Carmen's entrance), and an occasional turn of phrase in Carmen were, to the Spaniard, a pretty weak dilution of his heady native brew. In the same way that Puccini failed to be American in "La Fanciulla del West," Bizet failed to be Spanish in "Carmen," though, unlike Puccini, he wrote an opera in other respects so vital that it was a box office pillar before its second summer and has stood unshaken ever since, to the infinite joy of impresarios. (By the irony of fate, three months after the initial performance, which was coolly received in Paris, poor Bizet died, supposing his masterwork a failure, or at best a succes d'estime.)

Latterly the rest of the world has been finding out that Spain, in music, is not "Carmen." Curiously enough, it was by way of France,— whence came "Carmen,"—that this revelation came. It was Emmanuel Chabrier who did it, with his rhapsody "Espana," and, after him, three other Frenchmen, Debussy, Ravel, Laparra.

Rimsky-Korsakoff, the Russian, lent a distant but helping hand. The Italian, Zandonai, topped them off. Finally other Spanish composers joined in the good work. I speak less of poor Granados, who lost his life on the Sussex, than of Albeniz and the younger—and more popular—Valverde.

Pundits may object to the bracketing of those two names. But it happens that just now Valverde has held the New York stage for months with his revue (zarzuela) "The Land of Joy," and Spanish rhythms, Spanish dances, Spanish shawls, yes, Spanish slang, have been town talk. Albeniz, the greater musician, we are yet to become familiar with. Granados palely, Valverde in emerald, topaz, and vermilion, have blazed the trail here for Spanish music.

But Spain in other forms has lately been coming to the United States. We have seen Spanish plays, read Spanish novels, seen the canvases of Sorolla and Zuloaga; we have eaten garbanzos and puchero, danced the tango, and cherished Velasquez as a religion.

Now for the real Spanish music.

LET US first recall the fact that Spain has sent enough interpretative musicians into the world to have spread the gospel of Spanish music far and wide had they cared to do so. Here are some records.

Sarasate, the fiddler, a native Spaniard, counting his fame world-wide, was the author of six books of "Spanish Dances" for violin and piano and an "Andalusian Serenade" for the same instruments. Some of these are still played occasionally, but nobody thinks about them now as Spanish music. Indeed, few think about them at all.

Doubtless the foremost operatic family of history—taken by and large—is the Garcia family. The elder Manuel Garcia was a native of Seville. At the age of six he was a chorister ⅛ the cathedral of that city. It is significant that he composed no less than forty-three operas which saw performances on the stage, but though seventeen of those were ⅛ Spanish, he is now known not as a Spanish composer but as a major ornament of Italian opera in the several roles of tenor, teacher, and father. He died in 1832, only four years before his most celebrated daughter, Maria Malibran. The son Manuel, and the younger daughter, Pauline Viardot, surviving almost to our own day, kept the Garcia family tradition alive for more than a century.

New York owes to Manuel Garcia, the father, its first season of Italian opera, which he opened on November 29, 1825, with "The Barber of Seville." In his seventy-nine operatic performances he was assisted by a company that included his wife, his son Manuel, and his daughter Maria. His nearest approach to doing anything for Spanish music here was to present two of his own operas which he composed, to Italian texts, for his phenomenal daughter Maria.

Gayarre, a later Spanish tenor, entranced Europe in such widely separated operas as "Lohengrin" and "I Puritani." Del Puente, a Spanish baritone of no less fame, sang in Europe and America with Patti and Campanini forty years ago.

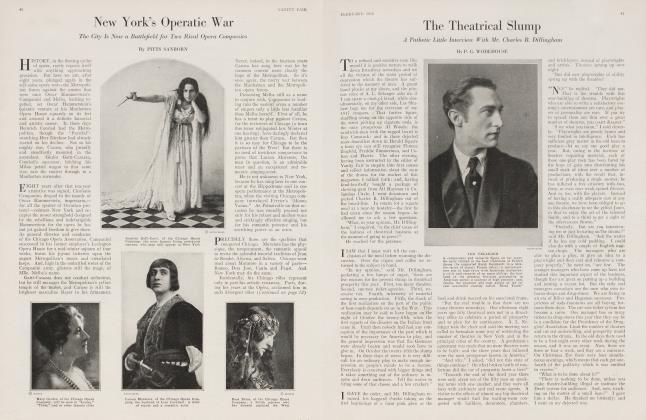

WE have many Spanish singers among us, There is the eminent concert baritone, Emilio de Gogorza, who now and then lets a Spanish folk-song creep into one of his programmes. Maria Gay of Barcelona crossed the seas from European triumphs bent on showing us the real Carmen. An obstinate public found this Carmen less real than several it already knew—Calve's and Bressler-Gianoli's.

Later, Lucrezia Bori of Valencia (now, alas, no longer here) beguiled us by her fresh and fragrant art. Then Maria Barrientos of Barcelona gave us her gossamer arabesques in highest coloratura. A Spanish tenor, Nadal, is now with the Chicago Opera association. The Spanish tenor, Lazaro, is on the Metropolitan roster. In the Valverde zarzuela, Maria Marco has revealed a soprano voice, and an ability to use it, which is superior to much of the singing heard in "grand opera." The basso Segurola, an excellent comedian, surveying life unruffled through his monocle, is always with us and lilts us an occasional Spanish folk-song. The rich voice of the Basque bass, Mardones, has also been heard with delight at the Metropolitan Opera House during the past season.

But none of these artists, save Maria Marco, can be said to have done much to acquaint the American public with Spanish music. Indeed, Luisa Tetrazzini probably did more to accomplish it by singing here a highly characteristic song from Ruperto Chapi's zarzuela "Las Hijas de Zebedeo."

(Continued on page 94)

(Continued from page 52)

THE first Frenchman to give us the real Spain in music was Emmanuel Chabrier. In 1882 he visited Spain to study, the Spanish dances, writing thence some singularly vivid letters. His rhapsody "Espana," the great musical fruit of the visit, was produced by Lamoureux at one of his concerts in Paris on November 4, 1884. So unusual and daring did it seem that the players themselves looked for a failure. But the reception by the public was such that Lamoureux repeated it at three consecutive concerts. Theodore Thomas led it in America in 1885.

" 'Espana,' " to quote the annotative Philip Hale, "is based on two Spanish dances, the Jota, vigorous and fiery, and the Malaguena, languorous and sensual. It is said that only the rude theme given to the trombones is of Chabrier's invention; the other themes he brought from Spain, and the two first themes were heard at Saragossa. The brilliance of the orchestration is indescribable, and the whole thing instead of cloying the hearer makes him greedy for repetition."

THIS, then was the magic of Spain done into tone. Debussy, Ravel, Laparra, all French, though the last two border on Spain, followed the lead. Debussy in his "Soiree dans Grenade," for piano, and in his orchestral "Iberia" evokes the atmosphere, the color, the very smell of Spain.

Ravel also evokes Spain, but with larger emphasis on the dance, in his "Rhapsodie Espagnole." Then there is his one-act opera, "L'Heure Espagnole," which has not yet been given in America.

The break from the "Carmen" tradition in opera came not only through this little work but through the "Habanera'-' of Raoul Laparra, produced at the Paris Opera Comique in February, 1908, and through the "Conchita" of the Italian Zandonai, which New York heard once in 1911. Laparra, who is his own librettist, has brought out another Spanish opera, "La Jota," and is now at work on a third, to be called "Le Tango et la Malaguena."

"La Habanera," a grewsome story of insistent passion, sudden crime and long remorse, has unluckily not been given in New York—not even so much as its thrilling orchestral prelude,—but there were several performances in Boston.

Laparra has also vividly mirrored Spain in many songs and piano pieces, and has latterly devoted some time to musical studies of the Spanish and Indian settlements in our great southwest.

(Continued on page 96)

(Continued from page 94)

The Zandonai opera was given by the Chicago company in several American cities, including New York. Objection has been made to the libretto, based on Pierre Louys's curious story "La Femme et le Pantin." Zandonai did not share the objection, for this score is immeasurably more vital than "Francesca da Rimini," which bears all the stigmata of having been written to order. In "Conchita," his evocation of Spanish atmosphere, Zandonai shows himself the peer, as well as the disciple, of Debussy in his "Iberia."

PIANISTS, hereabouts, who had been playing an occasional piece by one Albeniz, suddenly began to play pieces by one Granados. These were "Goyescas"—piano pictures in the mood of the great Spanish painter Goya, whom Granados admired exceedingly. He procured a librettist, shaped from the piano pieces a short opera in three tableaux, called it "Goyescas, and then the Metropolitan Opera Frouse duly gave it, two years ago, with three Italian singers and one American.

All that concerns that opera and the tragic death of its composer, a victim to German ruthlessness, on his way back to Spain, is matter of too recent knowledge for more than passing mention. Transformed into opera the pretty piano music of "Goyescas" proved feeble, a failure.

THERE was no more talk in New York of Spanish opera until the present season, when Valverde's "Land of Joy" blazed on the town with its dancing, its finery, its rhythms, its folkish melodies, all quite splendid and bewitching, and certainly, for us, quite novel.

And yet we are told this revue—or zarzuela—is no exceptional work; that it is one of dozens—or is it hundreds?

Valverde can string out melodies as his father—the greater Valverde, the Valverde of "La Gran Vian"—strung them out before him. "The Land of Joy" proved a charming operetta—I except the American intrusions,—and the dancing of La Argentina of Bilboa, and of Doloretes will not soon be forgotten by New Yorkers, nor the singing of Maria Marco.

So we find ourselves asking, why not more Spanish dancers from Spain, from South America; why not Pastora Imperio, the dancing Yvette Guilbert of Spain; why not authentic Spanish operas?

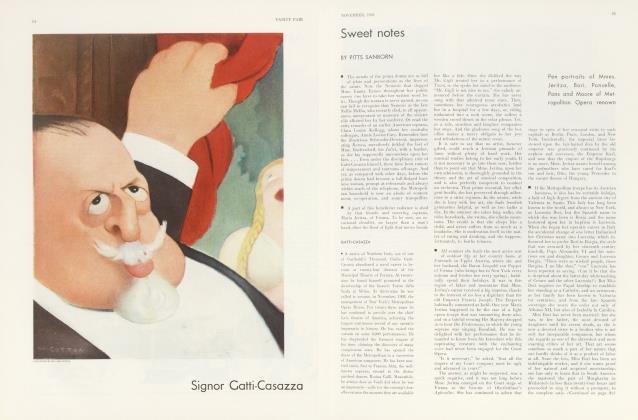

ONE recalls "Dolores," by Breton, which Oscar Hammerstein talked of giving at his Manhattan Opera House. Produced originally at Madrid in 1895, it has had success in various countries. Mr. Gatti-Casazza tells me the orchestration is bad. That fault could be remedied. There is an opera by Morera.

THE best of the Spanish composers seems to be Albeniz, who died in 1899. His last piano pieces cannot but excite the admiration of any musically sensitive person. In them one hears the Spain evoked by Chabrier, Debussy, Laparra, Zandonai. A curious phenomenon, Albeniz. Until he knew he must die he wrote little music of value. His several operas are, I am told, worthless. There is a symphonic poem, "Catalonia," which Josef Stransky announced for performance this season by the New York Philharmonic, but, up to the present writing, he has left it in the promissory stage. When the doctors read Albeniz his death sentence, he set out, in the time left to him, to write all that was in him. These last piano pieces of his are not easy to play—they demand a special crispness of touch that is rare in pianists, particularly the German-made. Perhaps somebody will one day specialize in Albeniz

THE burden of all this is that our appetite for Spanish music has been stirred. Despite "Goyescas" and the Frenchmen, the subject was still rather on the bookshelves when "The Land of Joy" took us all captive and made it all something to listen to, see, and talk about. Kurt Schindler's Carnegie Hall concert of Spanish music (prefaced briefly by Welsh) was indicative as well as delightful.

Through the Orfeo Catala of Barcelona Schindler secured rare choral music, sacred and secular, of the Spanish people.

WILL those contrasting forces, the pianists and the opera houses, conspire in their several ways to aid the progress, in America, of the scarlet and gold ofSpain? Will they make us all familiar with the Spanish rhythms, brutal or subtle, the susurrous merry-making, the wailing anguish, the sudden languour, the indomitable pride—all measured and attuned to one inevitable ground swell, the urgent, imperative, irresistible movement of the dance?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now