Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

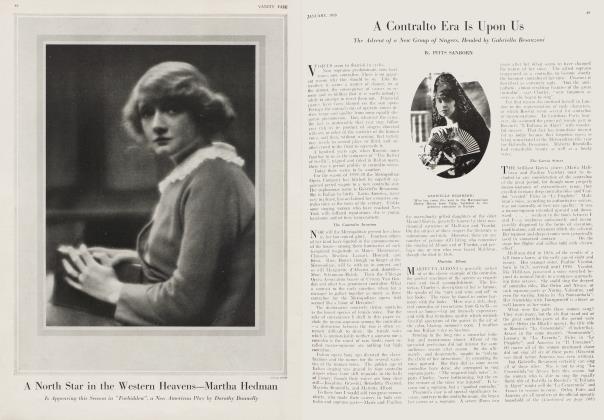

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Great Living Violinists

A Long and Noble Musical Category—From Eugène Ysaye to Toscha Seidel

PITTS SANBORN

HERE are fiddlers—in our very midst! Count the great ones now in America. Try to count the crowds, patient under wind and weather, lined up of an afternoon before Carnegie Hall to hear one of them, or trailing compactly around the massive square of the Metropolitan Opera House in the same interest of a Sunday night.

Our country, quickened to the mighty music of a world war, seems to be fiddle mad. The fiddler is a great magician—the bow his wand, the fiddle his incantation book. Great fiddlers are in our midst.

Jascha Heifetz, known to a few here by distant report in August, 1917, was a household word before the New Year. Nor is Jascha Heifetz the last—of whom the first is still Eugene Ysaye.

YSAYE, the giant of the violin; Ysaye, master of the "grand style" we none of us may define, but all may recognize; Ysaye, the Olympian; a mortal who can throw Jove's thunderbolt. Ysaye is the mighty bridge that links the violinists of to-day to the violinists of the great past. A pupil of Vieuxtemps, who was in turn a pupil of de Beriot, who was the disciple, if not strictly the pupil, of Viotti, the "father of modern violin playing," Ysaye thus stems directly from the great Italian violin school of the eighteenth century, the seed-pod of all subsequent fiddling.

Rich is the legend that has grown around the name of Ysaye from the day when the old Vieuxtemps, dying at Mustapha in Algiers, murmured a last wish that his living ears might hear once more the E string of his favorite pupil.

Perhaps the most characteristic anecdote is from our own country. Twenty years ago the two great Belgian fiddlers, Eugene Ysaye and Cesar Thomson, happened to be touring this country, not together, but at one and the same time. And it further happened that the exigencies of the tours brought the two virtuosi at one and the same time to the same small western city and to the same small western hotel. A reporter from the local newspaper was sent to interview Ysaye. Now, much had been written the country over about the two great men, and many and erudite had been the dissertations on the esoteric subject of violin technique. To close the interview with the proper flourish, the reporter ventured on the quicksands of that fascinating and dangerous topic.

"Oh, don't come to me about technique," said the master urbanely, as he dismissed his young interlocutor. "Why don't you talk to Cesar Thomson about that? He's stopping in this hotel and he is the greatest living master of violin technique."

As, ruminating this advice, the young man was descending the stairs, he suddenly heard the voice of the master booming from the landing above: "But, my young man, I give you leave to say this: that the greatest violinist that ever played without technique is Eugene Ysaye."

THE master must have chuckled to himself as he launched this ultimatum, for the fact is he has always possessed a very great technique, even if it has not invariably been apparent. Let us not forget that the young Ysaye was expert in the tight-rope antics of Paganini, in whose dizzy intricacies we marvel at Kubelik and Heifetz. Indeed, he gave Paganini programmes. And the Ysaye we know has solved the technical problems of the concertos of Tschaikowsky and of Brahms, the latter written "against the violin," whose musical contents were for his great technique and towering musicianship a very easy matter.

Ysaye is the last man who can make a Vieuxtemps concerto sound as if Beethoven wrote it, and, in the Beethoven concerto, his nobility, his poetry, his profundity of feeling are incomparable. Kreisler is sometimes cyclonic in the final rondo; with Ysaye it is the procession of the universe marching on its starry course.

A Belgian, father of five sons and daughters, Ysaye knows well the meaning of Prussian warfare. Here in America he plays less than of old, but a former admirer hearing him after the lapse of years found that he still carves out the whole block of the classic sonatas and concertos, as he still stands monumental himself like a block of his own carving.

NEXT to the old master in length of fame, among the violinists of our day, are Kreisler and Thibaud. Once an officer of the Austrian army, Fritz Kreisler has bowed to American opinion and closed his fiddle case for the duration of the war. A genuinely romantic figure, Kreisler, as he faces an audience with something of the defiant pride of a jungle beast and a tone that combines a throb and a thrill. He has not the grand style of Ysaye or his majestic and elegant sweep of bow, but he has, besides accomplished musicianship, an intensity and a verve that stir every audience. He is the best player of the Brahms concerto America has perhaps ever heard. He will probably be remembered here, by the greatest number of his auditors, for his incomparable playing of Dvorak's "Humoresque."

Jacques Thibaud, a soldier of France, has the supreme elegance of the French school, with warmth, too, and vivacity, and he alone among the younger men has something of the grand style of Ysaye. Of all the admirable fiddling heard here in the past season from many masters young and old, nothing surpassed Thibaud in two of the movements of Lalo's "Symphonic Espagnole."

Continued on page 98

Continued from page 54

LAST to come here, but older than these men and older than Ysaye, is Leopold Auer, literally the "master of masters" as he has so often been called. Professor Auer, arriving here in February, gave a recital in March, despite his three-score and more than ten years. For a long time we have known of him from remote Petrograd as a remarkable teacher. One pupil of his after another has come hither, and one after another they have shown us that they could play —Mischa Elman, Efrem Zimbalist, Kathleen Parlow, Eddy Brown, Jascha Heifetz, Max Rosen, Toscha Seidel. If Max Rosen disappointed the highest expectations, it is perhaps because his time with Auer had been so short. Auer himself explains his success as a teacher by saying simply: "I hear and correct their faults."

Court violinist to three czars, the old professor does not hesitate to say that he preferred America to the Bolsheviki. So, to America he came with a new fiddle fledgling under his wing,—Toscha Seidel, a still younger Russian than the Heifetz boy.

THE common characteristic of the real Auer pupil is a highly perfected mechanical facility. Technical feats that have puzzled the giants, these boys toss off easily. They all play the concerto of Tschaikowsky—most of them choose it for their debuts before a new public. And in some respects the Tschaikowsky concerto is the most difficult feat that can confront a violinist. And thereto hangs a little irony of musical life.

Tschaikowsky wrote this concerto for Auer himself, then at the height of his career as a virtuoso. He expected, of course, that Auer would play it, and so he dedicated it to him. But Auer found the work outside of the legitimate territory of the violin and did not try to play it in public. Bristling with difficult leaps, long stretches, and awkward passages for the bow, the work sought a performer in vain until Brodsky took it up and played it. To him Tschaikowsky then rededicated the score. Here Maud Powell introduced the concerto, doing only the opening movement at first, but later all three.

Auer as a pedagogue seemed to be seized with a vicarious passion for the concerto that he had once resigned, as it were, to Brodsky, and every finished pupil that emerged from the Auer studio thenceforth had that concerto with all its bristling difficulties at his finger tips. One brand of time's revenges!

OF the Auer output previous to this year Elman, Zimbalist and Eddy Brown have been prominently with us. The witchery of Elman's elfin bow, the honeyed richness of his singing tone, a manner whose warmth docs not shun easy sentiment have made him known the country over. Zimbalist, with his fine tone and great technical accomplishment, has steadily applied himself to the serious problems of his art and to composing. He heeds the voice of an exacting musicianship and tends the dignity of his art like a priest.

He is master of the Tschaikowsky concerto and he can dazzle with the fireworks of Paganini and of Ernst, but he prefers to play the concertos of Beethoven and of Brahms. Also, be it noted, he is an enthusiast for the younger contemporary composers, men like Cyril Scott and John Powell, and he does not balk at playing a composition because it is unknown. In fact, Zimbalist is one of the admirable propagandists, to use an overworked word, of all that is worthy in the new music.

ONG with the foregoing apostles of the gospel of Auer, one must mention such gifted American boys as Albert Spalding and David Hochstein, both in the army now, and Sascha Jacobinoff, Sascha Jacobsen, Elias Breeksin, and Samuel Gardner. The array is almost bewildering; the vintages commendable in their excellent succession. They all play well, exceedingly well, and they are not the last—not by any manner of means.

This season came Heifetz, and after that extremely significant fact, came Rosen, and thereupon came Auer himself and his brood of wing chickens.

Jascha Heifetz is the greatest technician of them all. Even Kubelik, that wizard of violin technique, in his greatest day did not turn the trick with the utter ease of the Heifetz boy, nor has anyone preserved from top to bottom of the scale and in the tiniest cranny of passage work, the flawless purity of the boy's tone. His musicianship is beyond a doubt, his sense of design as well as his sense of detail. Elderly and unemotional critics have discoursed on the Grecian purity, repose, and sense of form in his playing.

Once in a while a hearer complains that he lacks temperament, to which one wearied concert-goer was moved to respond "Thank God!" Perhaps Heifetz does lack temperament; then so does the angel of the lord that breathes upon his fiddle strings.

AND now Toscha Seidel. This fledgling, heralded as "another Heifetz," was to have been held over as a sensation for next October, but instead his managers decided that there is no time like the present, so he burst on an attentive universe on the fourteenth of April in Carnegie Hall. His success was tremendous. He was the last of the great fiddlers, perhaps, for this season.

When, in the fulness of time, Ysaye shall be no more, something, one fears, will have perished with him—the "grand style," the incomparably ! majestic and varied rhythm. But, withjnew players, new virtues arise. Forty years hence, Heifetz may set the standard. Reviewers will then lament that his grand style and 'his majestic rhythm can have no successor.

And so the little scribes run on, and so the great figures of the violin arise, make their bows, and pass on.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now