Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHints for Art Lovers

Ways of Recognizing the Work of a Truly Great Man

STEPHEN HAWEIS

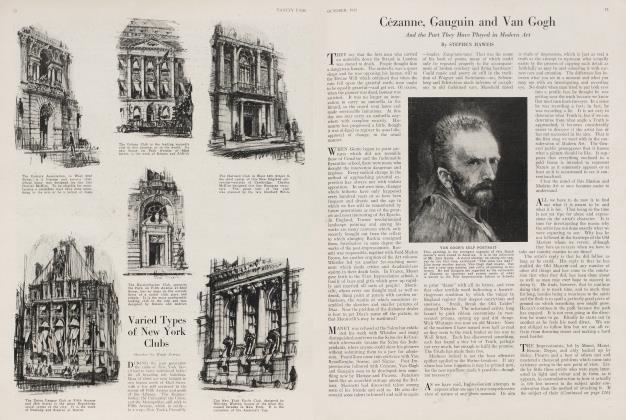

IF you ever see a picture which is entirely unlike any picture you ever saw before you may safely conclude that it is worthy of your consideration. Of your charity presuppose that the author is sane and has no special interest in affronting you, then try and find out what the artist was trying to do. It may be he has failed, but the end cannot be despised with any semblance of justice until you know what his aim has been, and it may possibly happen that the work you condemn may be the forerunner of something which is to be the standard in taste of future generations. A glimpse of the "expert criticism" which was offered in the best periodicals upon Whistler and Manet should at least make us very careful, for while the upholder of the existing order of things is usually applauded owing to our instinctive hatred of change, the man who opposes when he meets the irresistible force is smashed beyond recognition by the impact and his opinions are but feathers on the wind forever afterwards.

BUT if you see a picture which reminds you very forcibly of other pictures you have seen, think again before you pronounce the judgment that is forever struggling to get out and try to recall just what man's work it resembles and why. If you can unhesitatingly say: it is like a Bouguereau or a Sargent, consider whether the picture is an unintelligent plagiarism of a good thing or an intelligent appreciation of Nature faithfully studied within * the limits chosen by certain distinguished artists of the past, whether recent or ancient. Inasmuch as the master has dominated the painter, who has in no wise succeeded in surpassing him, it is not a first rate work of Art, for the greatest value in a work of Art must ever be what the artist has brought new to Art, in a word what he has created. Observe in conjunction with a superficial resemblance to other pictorial expression if the artist has expressed some one thing more vividly than you ever saw it expressed before. If he has, it is likely that the world will not be slow to discover and appreciate it also. It may even be of sufficient importance by itself to place that man in a class by himself, sufficient to rank him with the great men of his generation. As an instance of this one might quote Fritz Thaulow and his pictures of mill pools and rivers in flood. Many people have painted fine landscapes, but it is questionable if any artist before Thaulow succeeded with the forms of water under certain conditions as did he.

SO many pictures in the popular picture galleries are no more than naive statements more or less skilfully made, that their authors admire, not Nature, but this or that great man's appreciation of her. This being so, if a picture attracts you from any angle, enquire the age of the painter. Many a work is to be respected at twenty which would be a haunting shame at sixty. A young man may be finding himself by seeking among tha older Masters. Every young painter shows some influence and often many separate influences before he arrives at his own style, before he knows how to say what he has got to say, but if a painter has not produced his own interpretation of life, recognizably and conspicuously his own, long before threescore years, he must await his next reincarnation for the happy awakening.

Vast numbers of pictures may have very little real artistic value and still be worth any individual's while to have and to hold. Certain subjects, certain colors, certain associations may create a value in his mind, may create joy for him which an impassive art critic may know nothing about. Remember that he would not care if he did, as he judges the picture by its virtue, not as a mother judges the prowess of her child, "very good for his age." Far be it from me to object to a painting which fulfills any such mission. A fine Muirhead Bone etching or drawing is wasted upon a man who honestly prefers a chromolithograph of a cottage scene, or a ship in surprising difficulties upon a curly sea. Nor should the chromo owner do otherwise. There is no ought about it. He need not be "educated up" to anything—until lie chooses. He is at the chromo stage from which he will in time emerge quite naturally. If he does not desire anything better in the domain of Art, who knows but he may be applying his intelligence and appreciative faculty in other perfectly honorable directions?

(Continued from page 100)

WE have no business to object or " criticise him adversely. Freedom of choice is his absolute right in Art matters, but let him realize that what is true in his case is equally true in that of the professional artist. Art indeed is the first thing in the world to become free. For centuries it was held in the domination of the Church, for years public opinion tried to coerce and control it, but with the Post Impressionist movement Art attained its majority and is forever above the guardianship of well meaning relations. This is no small debt that humanity owes to such progressives and independents as Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso.

EACH generation produces its men of the first rank who come into their own automatically when a sufficiently long interval has elapsed for them to be seen in proper relation to their compeers. Each in turn is imitated by satellites with greater or less ability, these again are echoed and re-echoed until the sound of their little truth is attenuated and finally lost altogether in the strife of the market place. The chromo is the last gasp of something which as a rule was really fine and good in the beginning. The parallel in sculpture to the chromo is the plaster cast which small Italian boys sell to the undiscerning. Some of these very things were perhaps not so bad in the beginning, but they are reproduced in such quantities that the mould becomes choked and worthless —the cast has lost everything but its bare shape and all the delicacy of whatever modelling there was has been completely lost.

IT every Art epoch there are those who succeed and make money and others who fail and die of it. It occasionally happens that the successful man is also a great artist, but success is not an indication of worth by itself. David was one of the most successful painters in his day; his influence extended throughout Society and influenced Politics, yet he is not very highly rated now, nor ever will be again. Rembrandt and Velasquez are examples of artists upon whom Fortune smiled in their day, and of whom Fame will never tire. The list of those who were crippled from penury and who died in abject poverty, however, is long enough to be a lasting disgrace to the memory of those in whose age they lived. Nor are these dark ages over. Earnest Dowson and Richard Middleton are cases in point, though they painted with words instead of pigment while some of the contemptible patrons who drove Ralph Blakelock to the asylum are probably living yet in respected prosperity, though in the light of recent disclosure, they are probably not any longer boasting of their association with him.

HOW then shall the amateur know the Master when he appears? From the basest of motives there are many who would like to be able to recognize him in the hour of his need. It is not possible to give an exact formula by which genius may be recognized, nevertheless it seems strange that a flower of value may bloom unseen among so many seekers, for there are methods by which it may be discovered.

THE problem is easily understood as soon as we translate it into terms of horse, machinery, or stocks and shares. If a man wishes to buy a horse without any special knowledge of horse flesh, the last thing he does is to "go it blind" in a stable and make his purchase in the same way that he buys a picture from a gallery. He goes to a critic or reputable dealer, a man whose living and reputation depend to a great extent upon the advice he offers his clients. A man goes to an engineer about engines, he might do worse than to go to an artist about pictures. Now the honest critic of Art like the critic of anything else usually imagines that his taste is infallible and may sometimes give hasty advice through over enthusiasm for particular cases.

ON the whole he may b'e trusted as much as a layman can trust a stock broker or a clergyman. Neither, if he be a scrupulous man, will give his opinion as the last word that can be said upon the subject. The stock broker will put questions. What interest do you expect for your money? What risk will you entertain? Here is a good gamble in my opinion. There are some safe industrial investments. On the question of safety, though, he hedges. Advice on the gamble is his personal opinion and preference, but with the industrials you must choose for yourself among many by the light of nature. The stock broker guarantees a certain calibre and the critic can do likewise in matters of Art.

HERE are six young artists who show great promise. Here is my favorite for a gamble. This man may go up in value in ten years. Thesq others may or may not do so well. Success depends on so many things which are not always within a man's control. Health, perseverance in the face of adversity, marriage, sudden access of fortune are all things which may alter the natural course of things. They correspond to the advent of War, change of government, new inventions and the rest of the things which influence existing trade conditions, but it is safe to say that a man of ordinary intelligence with a little logical thinking might invest in pictures for profit alone with great success in exactly the same way that he invests in stocks or bonds or railroad shares.

BUT this has got nothing to do with Art. How may the great man be recognized? He is recognized first because he is different from others and not like. He is recognized because his work is individual and shows no strong influence of any one previous master. He is recognized moreover by the influence he exerts on his neighbors. Without an extensive acquaintance with works of Art of all ages it is impossible for the average man to find him at once through his work, but the more one knows of Art the more easily may he be found. The genius is perhaps easier to recognize in the flesh. We can usually feel a man's distinction if it is at all considerable. We can be sure of nothing, but a man of Art is Hot so very unlike a man of business or a man of leisure. If we know what he is and what he does, other than quite superficially, we shall not be likely long to waver on the subject of his calibre and value.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now