Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOur Auction Bridge Refuge

A Sanctuary and Retreat for Persistent, Not to Say Incurable, Bridge Addicts

R. F. FOSTER

AMONG the modem conventions which are in common use by good players there are three which are called "echoes", because they are intended to give an answer to a tentative play made by the partner in his leads.

Like all conventions, the echo consists in playing certain cards in what might be called an unnatural order. In following suit with small cards to the partner's lead of winning cards, for instance, the natural thing for the partner to do is to play the smallest card he has in the suit. But suppose he has only two small, and wishes to tmmp the third round? If he plays the higher card first, as soon as the smaller falls his partner will know that he is "down and out", and can ruff.

Good players restrict this echo to the king leads, because they know that the leader holds either ace or queen, or both, and will win the second round of the suit in either case, so as to be in a position to give the ruff. Many players use this echo on the declarer's suits, but it is not always advisable to show him just where the dregs of his suit lie.

Some players use the same echo to show they can win the third round of the suit with the queen. This is called the "come-on" echo. When there is a tmmp, the objection to its use is that it then has a double meaning, as the leader never knows whether his partner can trump, or has the queen. All double-meaning plays should be avoided. At no-tmmp it is all right.

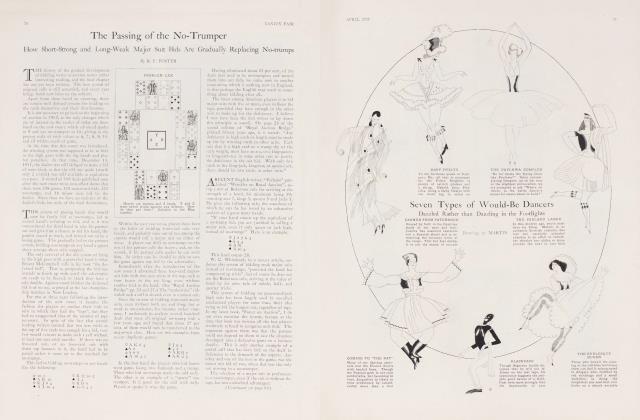

There is a little detail about this echo which many good players overlook. It frequently happens that dummy also can tmmp the third round of a suit. In that case an echo by the third hand should never be made unless he can over-trump dummy, otherwise the echo is misleading. Here is a deal in which the third hand failed to take this into consideration:

Z dealt and bid a heart, A two clubs and Y two hearts, which all passed. A led the king and ace of clubs, upon which B thoughtlessly played down and out with the seven and four. A took it for granted that B could over-trump dummy, and must then lead a spade up to weakness, which saves the game.

But dummy trumped with the queen and led a small trump, on which the declarer finessed the nine. After picking up both of B's trumps he led the queen of diamonds, overtook it with the king and got two spade discards, winning four odd and game.

If B suppresses the echo, on account of his inability to over-trump dummy, A will shift to the spades, and whether he begins with the ace or a small one does not matter, three spade tricks save the game, as A and B already have two club tricks at home.

Problem VIII

Here is one of Harry Boardman's best, with a whole month in which to solve it.

There are no trumps and Z lca^s. Y and Z want five tricks against any defence. How do they get them?

Those who send in answers to these problems frequently ask how full an explanation is demanded in order to secure credit for a correct solution.

It is not necessary to give every card played, unless the size of the card, or the nature of the discard, is vital to the solution. The important points are the original lead, and the order of the leads that follow, with any important variations in the defence that might require to be met,

The Answer to the October Problem will be found on page 106.

AS the open season for charity games, and large gatherings of more or less promiscuous players is upon us, a few hints on the proper management of these affairs may not be out of place.

When there is a prize for every table, and all the prizes are identical, at least in value, the players who make up a table and remain there, without any progression to other tables, may safely be left to their own devices, to play anything they please, from pitch-and-toss to manslaughter. But when it comes to progressive games, or to the more popular giving of valuable prizes for the highest score made at any table in the room, there are several complications that require attention.

The bane of charity bridge games at which there are valuable prizes for the top scores has always been the privilege of doubling. As soon as one of the four at a table gets behind, there is nothing to be lost by doubling everything and being redoubled. If the doubles are sound or lucky, the one that is behind comes out ahead; if they are reckless doubles, some one at the table gets a tremendous score and wins the prize. It is always nice to have a friend win it, if you cannot.

The laws of auction require the lower score at the end of a rubber to be deducted from the higher. Under this rule, the average rubber is worth about 400 points, and an exceptional one would be 1,000. This is never done in charity games, as the players keep all they make, and do not care how much they lose, as it is never deducted.

This is one of three rules that are constantly violated in these large semi-public games. The others are counting easy aces at 20 for each side, and playing three games to a rubber, whether the first two are won by the same partners or not.

As it has been found impossible to stop this sort of thing, however unfair it is to other tables in the room, the only remedy seems to be to render abortive these various unsportsmanlike devices for running up a big score.

Long experience has proved that if the game is legitimately bid and played, there is something wrong about any individual score that exceeds 1,250 points, yet dozens of scores are turned in at these charity games that run between 2,500 and 4,000.

Two or three years ago, at the request of the late C. A. Henriques, secretary of The Whist Club in New York, and committee on laws, a scheme to counteract this evil was devised, and was tried out by Mr. Henriques in the games he managed that summer, and by myself at the Ritz-Carlton that winter.

The object being to give a prize to the highest score when any number from 40 to 100 tables were engaged, we first ascertained what the highest legitimate score would probably be in such a game, keeping everything, without deducting. This we discovered to be 1,600 points, while the average of the ten best scores in 500 examined was about 1,000. The scheme was this:

Slips bearing every fifth number from 1,000 to 1,250 were placed in one envelope; from 1,251 to 1,500 in another; from 1,501 to 1,750 in another, and sealed up, unmarked. As fast as scores were gathered up by the ushers and taken to the prize table, they were sorted out into hundreds, keeping all between 1,100 and 1,200 together, etc.

(Continued on page 104)

(Continued from page 65)

As soon as the last score was turned in, one of the three envelopes was selected blindfold, opened, and a slip drawn from it blindfold. The scores most closely approaching the drawn number, above or below, are the winners.

Suppose the number drawn to be 1,240, and the scores nearest to it, readily found in the 1,200 to 1,300 pile, are 1,236, 1,280, and 1,196. They would win 1st, 2nd, and 3rd prizes in that order. Of course, this is all luck, but so is everything connected with a charity game. The scheme is at least absolutely free from fraud, and makes it useless for unscrupulous players to pile up a score that is open to the suspicion of being arrived at by collusion.

Hard Luck Hands

A CORRESPONDENT has been good enough to call our attention to the fact that there are two kinds of hard luck hands; those in which the cards do not lie right for any play we make, and those in which the adversaries do not play right for the cards we hold.

It is undoubtedly true that there is a great deal of luck in the way the adversaries play a hand; a slight difference in the selection of a suit to lead, a peculiar discard, a too hasty winning of a trick, may change things in a way that no skill could have done.

Here is a hand that was played in a duplicate game last winter which might be framed as an example of hard luck. The declarer at six tables out of seven went game, and at two tables he made an extra trick. At one table, one of the best players held the declarer's hand and reversed the score. Here is the distribution:

Z dealt a bid no-trump, which every one passed. At six tables out of the seven, A opened with ace queen of diamonds. Z then led the king of clubs, and on finding four to the J 10 with B, while A was discarding the encouraging 7 of hearts, he led a spade, and finessed the jack.

Having no diamonds to return, B led the heart and Z put on the ace. Another spade allowed Y to lead the club 9 through B, covered by the 10. A third spade put dummy in again to make the fourth spade trick and lead another club. This enabled the good players to get four odd out of it.

When this deal got round to one table the score turned in was just the reverse of this, the declarer being the one that got only three tricks. This is how it happened.

The contract was one no-trump, as usual, but the lady who had the lead had been taking lessons from another lady, and had just been told never to lead away from suits headed by ace and queen, especially against no-trumpers. Not having heard that the addition of the jack makes quite*a difference in this rule, she opened with the deuce of hearts, and the eight forced the ace.

One lead of clubs disclosed the situation, and Z saw that his only chance was to get dummy in with a spade finesse, which would give him at least three spade tricks and the double finesse in clubs, if the spade king was with A. But the finesse in spades lost to the king.

Not knowing anything about the diamond suit, B naturally returned the heart and found himself still in the lead on the fourth round. The diamond lead was practically forced at this point, and, of course, A made all six of that suit, losing nothing but a spade trick at the end.

Here is another dose that a very good player had to swallow, the principal ingredient in this measure of hard luck being that the original leader was thinking about something else, and forgot that spades were not trumps. This was the distribution:

Z dealt and bid a heart. A passed and Y denied the hearts with a spade, which B passed. Z could not stand the spades and bid no-trump, which held.

At every table but one A either led through the denied spade suit or opened with the club queen. If the spade was led, dummy put on the ace and led the diamonds. Now, in spite of anything A and B can do, Z can establish the diamonds before losing both his reentries in hearts. This wins the game, with three by cards.

As the play actually went at one table, A won the first diamond trick and led another spade, dummy allowing both ten and king to win. The next lead was a heart, and the rest was easy.

But at one table the lady who held A's cards seemed rather astonished at being told it was her lead; but without asking any further questions, and under the impression, as she explained afterwards, that spades were trumps, she led the singleton heart.

It is now impossible by any play to make the diamond suit, as one of the reentries is taken out too soon. No matter what Z leads, naturally a diamond, B gets in and clears the hearts. In the actual play, B won the first lead of diamonds. A won the second, and led the spades, B winning the trick with the ten and making the rest of the hearts, upon which A got rid of all his spades.

When B led the club ten it became evident that dummy had lost a trick by discarding down to the ace queen of spades. Otherwise he might have won the club and put B in again by leading ace and queen of spades, so as to make the long spade at the end, instead of which he lost a trick to the queen of clubs. The result was that Z was set for two tricks, instead of winning the game, and all because a lady forgot that spades were not trumps!

Ladies' Day at the Club

THE usual formula for a "bridge afternoon" at a country club seems to be to appoint two or three ladies to act as hostesses, and incidentally to supply the refreshments, and for the members of each little clique to make up their own tables. As a rule, there is no stake, and the style of play is strictly in keeping with the general run of auction when played "for fun".

(Continued on page 106)

(Continued from page 104)

A card turned up in dealing does not seem to make any difference. If it is an ace, Mrs. Dresser simply smiles, and says, "Do you mind, dear?" and, of course, the charming Mrs. Smith says no, so the deal proceeds. This was the distribution of the cards in the first hand Mrs. Dresser dealt. I did not wait to see any others!

Mrs. Dresser bid one no-trump, Mrs. Smith said two hearts, Mrs. Jones two no-trumps, Mrs. Brown three hearts and Mrs. Dresser three no-trumps, which went round to Mrs. Brown, who doubled, Mrs. Dresser redoubling. Why not? Her partner must have the hearts.

Mrs. Smith led the heart jack and dummy's cards were laid down with the remark: "I helped you because I could stop the hearts, my dear. You know it was Mrs. Smith that bid the hearts, and I supposed she had both ace and king."

No penalty being demanded for this reference to the bidding, after the final declaration has been made, it is presumed that neither Mrs. Smith nor Mrs. Brown were aware of the existence of Law No. 51.

After five heart tricks had been piled up against her, upon which Mrs. Dresser discarded three diamonds, one club and a spade, Mrs. Brown led the jack of clubs, upon which Mrs. Dresser put the queen. The king won, the deuce was returned and the ten forced the ace.

Mrs. Dresser then led the ace of spades and caught the lone king, Mrs. Brown playing a small club, which impelled Mrs. Jones to exclaim: "Why, where on earth are all the spades? Why on earth didn't you bid spades, my dear?" to which Mrs. Dresser rejoined: "Why I had three aces, my dear."

Mrs. Dresser and her partner were evidently oblivious to the fact that under Law 86 a player who corrects a revoke in time to save the usual penalty can be called on to play her highest or lowest of the suit led. By calling the high spade, Mrs. Dresser could have made the whole suit. As it was the queen killed dummy's jack, Mrs. Smith discarding diamondsr The return of the club held the declarer down to three tricks.

The subdued shriek of delight with which Mrs. Brown, who was keeping the score, announced that they got 500 for that was promptly squelched by her partner, who reminded her that Mrs. Dresser had redoubled, and that it was 1,000, which was stoutly denied by Mrs. Jones, who insisted that she did not hear her partner redouble, or she would certainly have bid spades or something, and in the discussion the fact that the contract was actually set for 1,200, instead of 1,000, was entirely lost sight of.

Answer to the October Problem

This was the distribution of the cards in VII, by Prof. T. J. Wertenbaker, of Princeton University, U. S. A.

Hearts are trumps and Z leads, Y and Z want only three tricks, but against any defence. This is how they get them.

Z leads the spade, which Y trumps and leads a diamond, B winning the trick with the nine or seven. If B return the diamond, Z discards a spade. Now B must lead a trump, which Z wins with the king, returning the eight, which A wins with the jack. Now nothing can prevent Z from making the ten.

If B leads a trump, instead of returning the diamond at the third trick, Z will play the king and lead a spade. B can either trump or discard a diamond. Whichever he docs, Z must make one of his trumps.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now