Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowCommon Faults in Bidding at Auction

Where Most of the Average Player's Money Is Thrown Away

R. F. FOSTER

LEAVING out of consideration exceptional hands, strong enough to bid three or more immediately, we find this rule: Any suit which is good enough for the trump, but not good enough to assist or to oppose another declaration, should never be a free bid. The player who will consistently keep this simple precept in view will avoid one of the most common faults in the bidding at auction.

Secondary Bids Defined

ALL such suits are secondary bids. That is, they should be reserved for the second round, and declared then, if a favorable opportunity offers, after having refused to bid them on the first round.

There are three classes of secondary bids, and the player who fails to distinguish between them in his declarations must be considered as at fault. The first class are those bids made on the second round after having passed the first opportunity for a free bid. The second class are bids in a major suit after having bid a minor suit on the first round. The third class are bids of a lower ranking suit after having bid one of higher rank on the first round. It is with the first class of secondary bids that we have now to deal.

Suppose the dealer passes, one of the opponents bids a heart and the dealer then bids a spade. This indicates that while the spade suit is good enough for the trump, it is not good enough to be of any assistance for a different declaration by the dealer's partner, nor strong enough to win any sure tricks against the opponents' heart contract. Length is probably its only qualification, five cards or more.

Such bids are seldom at fault, although they may be a trifle optimistic at times. As they are seldom doubled, they may score honors against a loss of 50, and they at least have the virtue of leaving the partner under no misapprehension as to the assisting or defensive value of the suit named, provided he understands the characteristic of secondary bids.

This brings us to another common fault in bidding, which is the failure of the partner to make due allowance for the fact that the bid is secondary, and that the suit cannot be depended on for the high cards that would be indicated by a free bid. To assist such bids without the extra strength to make up for their weakness is one of the most prolific sources of penalties at auction.

The situation is entirely different from the forced bid, which overcalls an opponent's free bid, as when the dealer bids a heart and the second hand a spade. The forced bid may be quite strong enough to have been a free bid, had the dealer passed. This is never true of secondary bids.

The chief value of shifting a bid into the secondary class is that it warns the partner to be cautious about pushing matters or doubling. It is also useful in warning him that he will not find much assistance for a bid of his own, in case he is inclined to shift to another declaration that looks promising. It is strictly a defensive bid, not to be carried too far by the partner. Here is a good example of its value as a warning to be cautious, and of the result when that warning is not given:

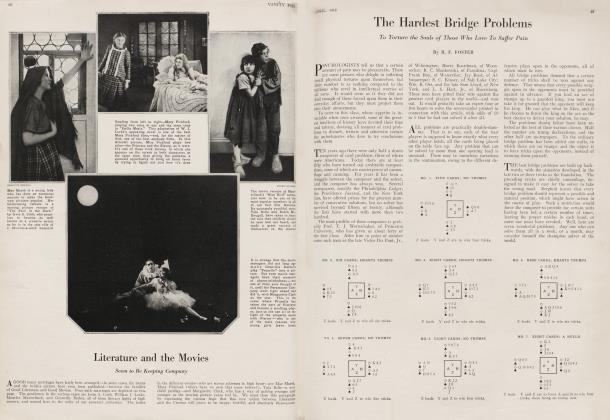

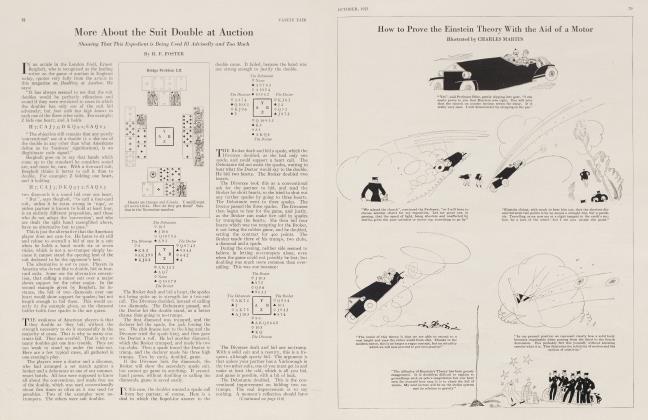

When Z dealt and passed, A bid a club, and

Y passed, being satisfied to save the game against a minor suit, even with Z's indicated weakness. When B passed, Z trotted out his secondary heart bid, which A passed. This informs Y that Z's hand is good for little or nothing unless hearts are trumps, but that if is good enough to put up some kind of a fight against the adversaries' clubs. Observe that if Z is left to play the hand, he will make his contract.

B went to two clubs, and Y assisted the hearts once only. He is willing to be set 50 to score honors and prevent an adverse score in clubs, but when they went to three clubs,

Y passed, having in mind the secondary nature of Z's bid. A made his contract, three by cards in clubs.

At some tables Z bid hearts originally, and this induced Y to assist the hearts over A's bid of two clubs. The result was that when B went to three clubs. Y went to three hearts and was set. From the free bid he counted on finding both king and queen of hearts in Z's hand, with some outside sure tricks. At one table Y doubled the three clubs, which allowed A to win the game. In both cases the loss is due to Z's initial error in making a free bid on a suit that is good enough only for a secondary bid.

Continued on page 64

Continued from page 44

Bidding Hands Twice Over

ANOTHER very common fault is bidding upon tricks that have already been included in the partner's bid. The minimum strength for a free bid is four tricks out of the thirteen to be played for. But any declaration must undertake to win at least seven. Where does the player who bids on four expect to find "the remaining three? In his partner's hand, of course. Then three tricks in his partner's hand are included in the original bid, and if the partner has only those three tricks and yet assists, he is manifestly bidding his cards twice over.

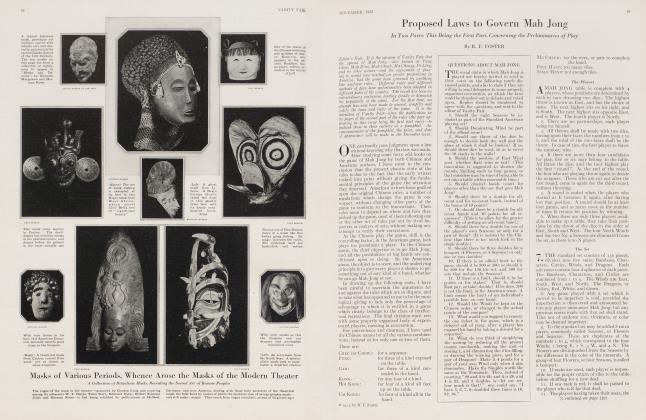

All bids are made on averages, and the dealer who bids on four tricks expects his partner to hold his share of the remaining nine, as there is no apparent reason why he should have more or less than either of the opponents until further bidding shows that the distribution is unequal. The normal distribution may be illustrated in this way:

The partner's three, combined with Z's four, will make up the seven which Z undertakes to win when he declares.

But the moment an opponent overcalls, the probability of this equal distribution disappears, and it becomes Y's turn to assume that Z's hand is nothing extraordinary. If it is, he will rebid when it comes to his turn. The fault which probably loses as much as anything at auction lies in Y's assisting the dealer when the cards he holds have already been included in the dealer's original declaration. Take this as the situation:

Z bids a heart and A a spade. Y has no bid, unless he is willing to take a sting, and deceive his partner at the same time. Unless Z can win more than four, or Y more than three, they cannot make eight tricks. On the other hand, it is doubtful if A can make seven, and almost certain that he cannot go game.

This fault, forgetting that the partner has not seven tricks in his own hand when he bids to win seven, leads to most of the big losses that we see at the card table. Almost all the overbidding is started, and usually finished, by the original bidder's partner. "With ninety-nine players out of a hundred, the assist is 'largely a mixture of guesswork and hope," as one writer puts it. Here is an illustration, a deal that went the rounds of a duplicate match last winter:

In duplicate matches, it should be explained, the same cards are held under precisely the same conditions by various persons at different tables. It is by an examination of the results obtained that we are enabled to verify or to correct certain theories or principles of bidding and play.

Z dealt and bid a heart, A a spade and Y two hearts. B assisted the spades, and Z passed, showing that he had nothing more than his original bid of one heart, or four tricks. This did not stop Y, who went to three hearts and finally to four, over the spades, which B continued to assist. The result was that Z was doubled and set for 300, as his opponents got home three spades, two diamonds and a club before they let go of the lead.

When Trumps Are Worthless

If we examine Y's cards carefully we shall see that he is evidently carried away by his big trump holding, five to two honors. But in spite of this his cards are good for no more than the three tricks his partner counted upon, and with the aid of which Z would have made his bid, one heart. It is true that Y has five trumps, but they are worthless, for the simple reason that he cannot trump anything, and they all fall uselessly on his partner's trumps at the end. The king was the only one he took a trick with, as Z won the third round of diamonds himself with the ten.

The players who did not assist the heart with Y's cards, or who did so once only, stopped A from going game at spades by leading the hearts, which Z won, and led the clubs, eventually making, two clubs and a diamond, as well as the first heart trick. One table, leading the trump from Y's hand, lost the game, as A was able to establish the diamonds before losing his re-entry.

The fault with assisting bids almost invariably lies in attaching too much value to trumps, and failing to consider what can be done with them. Few players make any mistakes in their estimates of aces and kings, but they continually overlook the fact that trumps, in the dummy, are of little value unless there is some very short or missing suit that can be ruffed early in the play. The curious part of it is that when this is the case the value of the ruff is so frequently underestimated or entirely overlooked. The ability to ruff the first round of a suit is as good as two tricks. A sure ruff on the second round is equal to a trick, and the two combined, if there are at least four trumps, no matter how small, is equal to three sure tricks.

Another fault, which might be touched on in passing, is attaching too great a value to high cards in the opponent's suit, and assisting the partner's bid, when the trumps are very weak. Suppose the dealer bids a heart, second hand a spade. The A J 10 of spades is no excuse for assisting the hearts if the third hand has only one or two small hearts in his hand. The first principle of the assist is to show the trump holding. On the second round of the bids, it may be opportune to show the control of spades by doubling.

Why the same person should overestimate a hand that cannot ruff anything, and underestimate one that can ruff an entire suit, it is difficult to understand, but a little observation of the average player's assists will convince anyone that such is frequently the case. Here is an example:

Continued from page 64

Continued on page 66

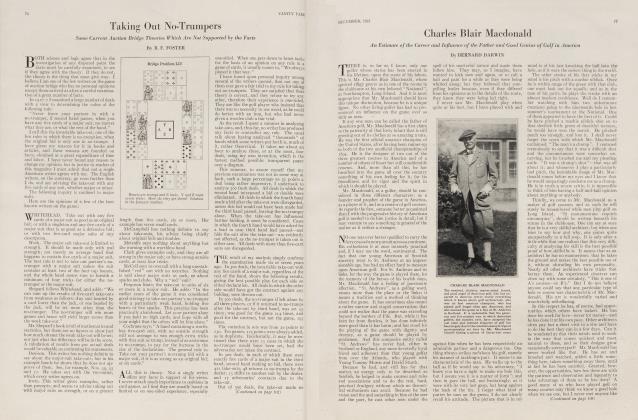

Z dealt and bid a spade, A two hearts, Y two spades. B and Z passed, but A went to three hearts, which Y passed, with the idea that he could probably set the heart contract, or at least save the game, as he ought to make two trumps and the ace of clubs, even if he does not get a chance to ruff a diamond.

It is evident that Y entirely overlooks the importance of the fact that he has no diamonds, and of the addition which that makes to the value of his hand as an assistance to his partner's spades. It is true that no one has mentioned the diamonds, and Z may have that suit, so that it will not be necessary to trump it. But that is no excuse for Y's failure to estimate four trumps and a missing suit at the normal value, which is three tricks, and to bid accordingly. Y's hand is actually stronger, in its trick taking possibilities, than the dealer's, with spades for trumps.

As the three-heart bid was allowed to stand, without doubling, A played it, and was set only two tricks, less simple honors. The opening lead was a spade, A returning a small club. Z led the diamonds, and Y trumped the king, leading another spade. Another club forced the ace and A trumped another spade, leading the top diamond, which Y trumped. When Y led the fourth round of spades, A trumped with the queen and led the seven of clubs, B shutting out Z's trump with the nine and leading the deuce.

Imagine Y's astonishment when he found that almost every other player that held his cards had gone on bidding spades and that Z had made a little slam. A opened with the king of diamonds, to show his re-entry, as his hearts were not solid. Y trumped and led a small club. The queen of diamonds forced the ace, which Y trumped. Then Z trumped the third round of clubs and led the winning diamond. Y trumped the next diamond and led another club, which Z trumped and led the hearts. As roon as Y made the king he led the trumps through B to Z's major tenace.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now