Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOur Auction Bridge Refuge

R. F. FOSTER

A Sanctuary and Retreat for Persistent—Not to Say Incurable—Bridge Addicts

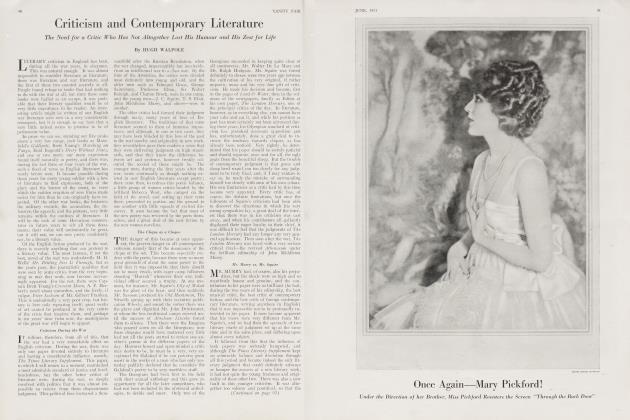

THEY were sitting on the hotel porch after dinner: a widow, who played bridge at every opportunity, and used to boast she never took a lesson in her life; a pretty girl, whom she was chaperoning for a southern tour; a tennis player, and a golfer—both devoted to the girl. They were discussing the subject of the rotten luck that came to each of them in their favorite sports.

The tennis player had had a bad day, most of his returns going into the net through being just an inch too low. The golfer had been in every bunker on the course, through driving a longer ball than usual. The girl had been king-fishing, and her hook was just a little too small, or something, so that she lost all the big ones. The widow had lost rubber after rubber that afternoon, because every finesse she made went wrong.

It was a hard luck story all round, but the only one who received any sympathy was the girl, each of the others being convinced that the bad luck of his friends was chiefly due to bad play. There being only one game in which it was possible for the luck to change before the morrow, Mr. Barton, the golfer, proposed to make up a rubber, and give the widow a chance to change her luck at bridge, a game in which he was rated as rather clever. The cut brought the Widow and the tennis player together.

"I'm sorry for you, partner," she apologized. "I'm so unlucky at this game. Every time I finesse I'm sure to lose, and Mr. Barton is such a shark at the game. No one can beat him."

The golf player smiled his acknowledgment of the compliment, remarking, "If every finesse you make goes wrong, it will not be our skill, but the cards, that beat you. I am very curious to see how many finesses you miss. Suppose we have a little side bet on them, just to make it interesting; say a dollar each?"

"I don't quite understand you."

"Every finesse you lose, I owe you a dollar. Every finesse that wins, you owe me a dollar."

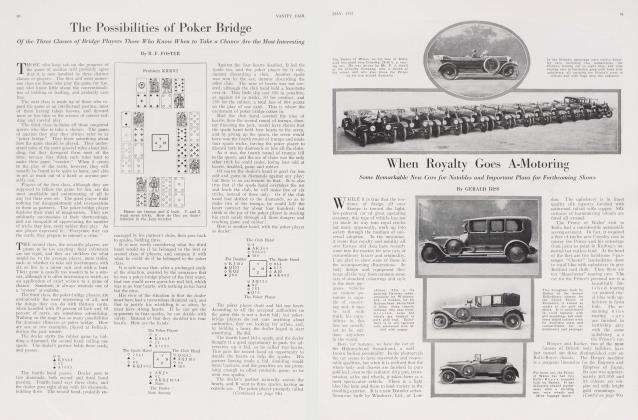

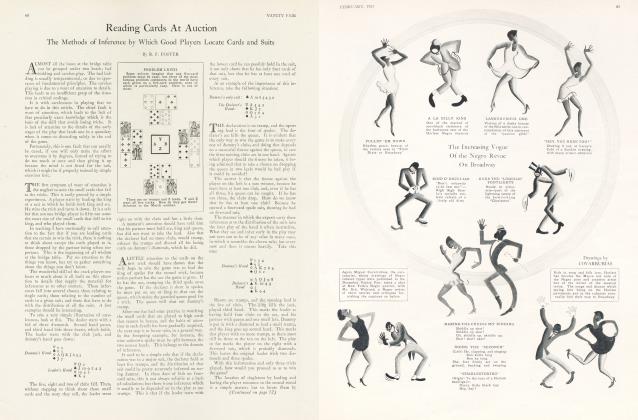

This being agreed to, the game began. During the first game, the Widow was dummy twice and against the declarer the other time, so that there was no action on the bet. On the second game of the rubber, having won the first, she dealt and bid no trump, her partner going to two no-trumps when the second had passed. This was the distribution:

The Tennis Player

The Golfer led a small heart, dummy played small, and the jack drove the ace. After studying the situation for a moment, the Widow led the jack of clubs, letting it ride, and the Girl won it with the queen.

S. C. Kinsey, the composer, calls this problem The Royal Slam, or The Downfall of Monarchy. The problem is to put four kings out of business.

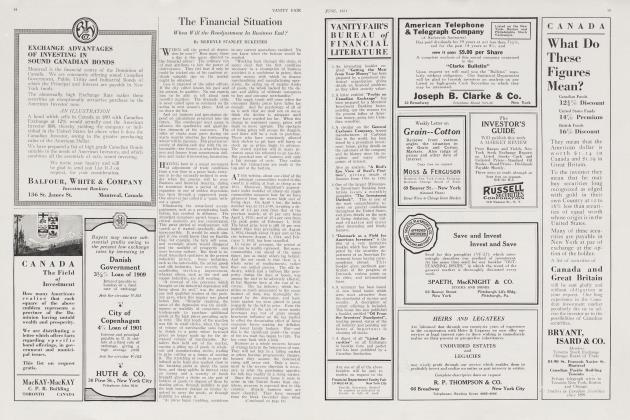

PROBLEM XXV

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want all eight tricks. How do they get them ? Solution in the July number.

"There! Didn't I tell you I could never win a finesse?" The remark brought no comment from the golf player, who was studying the dummy's cards with his usual care. Three winning hearts followed, dummy discarding two spades, the Widow a diamond.

A small spade was won by the Girl with the ace, and the ten was returned, which the Widow covered with the jack, losing the trick to the queen.

"There it goes again! I never saw anything like it. Why is it I can never win a trick by finessing?"

Still no comment from the Golfer, who went right back with the eight of spades, hoping to postpone the time when dummy should be in the lead with that ace of diamonds, and would have nothing but clubs left to lead. Dummy discarded a small diamond on the third spade.

The next lead from the Widow's hand was the queen of diamonds, the Golfer craftily dropping the ten. Dummy passed up the queen, and the Girl was in again with the king, while the Widow gave another gasp, and the Girl thought it was only generous to remark that her guardian did seem to have rather bad luck finessing.

"Oh, it's nothing unusual," rejoined the Widow; "but this is the first time I have ever made any money by being unlucky. Mr. Barton will owe me about a hundred dollars if we play long enough."

Even this did not bring more than a smile from the Golfer, which may have been because he at last saw his hopes realized, when dummy had to win the return of the diamond and lose the last trick of all to the ten of clubs. As he put down the score he remarked:

"Your partner went two no-trumps, and we won eight tricks, so you are set a hundred and fifty, less thirty aces."

"And put down three dollars for three finesses that went wrong in that hand," directed the Widow, tapping the score-pad with her fan.

"Pardon me, but I did not see you finesse anything," he corrected, smiling blandly. "You should have finessed the queen of hearts on the first trick, but you did not do so. You threw away the jack of clubs, the jack of spades and the queen of diamonds; but none of those plays were finesses."

"Why, I never heard of such a thing," looking at her partner, as if for moral support. Feeling called upon to say something, the tennis player could only shrug his shoulders.

"I don't like to appear impolite, but I am afraid, as there is a bet on it, that I shall have to agree with Mr. Barton. I thought it was a game hand, with the assistance I gave you."

"I shall be glad to leave it to any authority you select. We can easily recall the hands," suggested the Golfer, who started to put down the cards. "If you like, I'll make it fifty more that you did not make a conventional finesse even once."

That both these gentlemen were correct was the decision of the referee. No conventional finesse was made, and it was a game hand if properly played.

Perhaps some readers of VANITY FAIR would like to try it. There is no possibility of preventing the Widow and her partner from going game and rubber if the hand is properly managed. Any correct analyses of the play sent in will be gladly acknowledged.

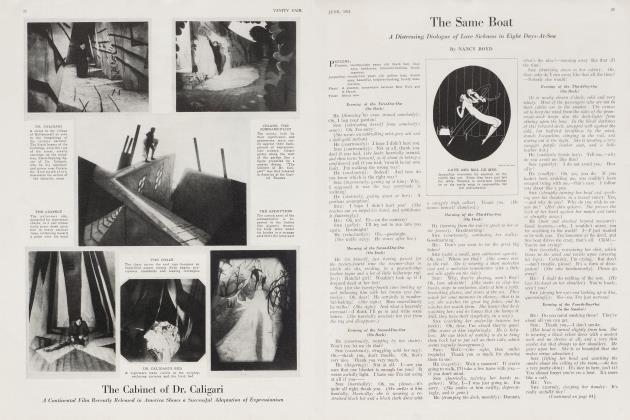

SIDNEY S. LENZ, whose portrait appeared in VANITY FAIR for April, 1919, is nothing if not original. He has just borrowed from the game of baseball a term which is peculiarly suited to a certain situation at the bridge table. This is forcing a player to unguard one or other of two suits by what Mr. Lenz calls "the squeeze". No text-book gives the play.

The opportunity for this play is more common than would be imagined; but it takes a very good player to see the chance to try it. Two things are essential. In the first place, one must be able to place cards with unusual accuracy. In the second place, one must be a good enough player to bring about the desired situation, with the lead in the right hand.

In some hands the squeeze play is forced upon the opponents in spite of their best defence; in others the opportunity for it is given through their own fault in slipping up on some detail of tactics. Here are examples of both cases, the hands being from actual play:

Continued on page 80

Continued from page 63

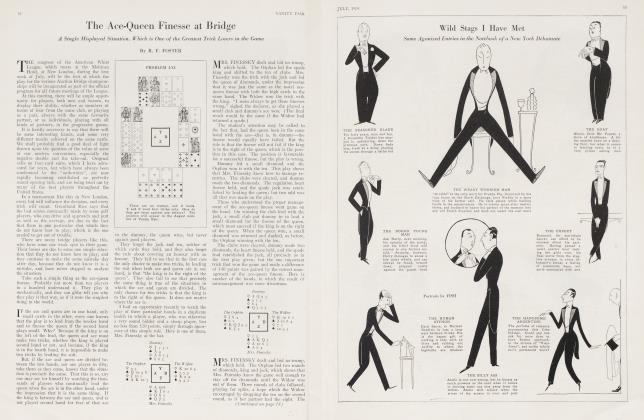

Z dealt and bid no-trump, A leading a small spade, and the king killing the jack, to conceal the queen. Z hoped to drop the hearts, so as to make four tricks in that suit, and led out ace and king. On the second round, A discarded a club. This marks B with the jack ten of hearts, so Z shifts to the spade, leading a small one to dummy's ten.

A put on the ace, and got an encouraging discard of the club eight from B. Dummy passed up the club seven and B put on the nine. This marks him with both queen and ten, and two suits stopped. Whether he has more clubs, or is all diamonds outside, Z proceeds to find out by applying the squeeze.

The spade queen holds the lead, and B discards a diamond. Another winning spade and dummy lets go the small heart, while B sheds another diamond. Now he is marked with two diamonds, or a diamond and a club besides his four known cards. As he will not discard a heart or a club, and dummy has discarded the small heart on the last spade trick, Z leads a heart and makes the queen.

Now the ace of diamonds, followed by the ten, so as to be sure that Z shall be in the lead, completes the squeeze play; because when Z leads the third diamond, B must either give us the heart jack, and let Z make a trick with the five, or he must unguard the clubs, and let dummy make both ace and jack.

The squeeze play in this case gives the declarer a little slam; yet the average player would probably be well satisfied with three or four odd. At one table at which this hand was played he did not even go game, stopping at two by cards. He made his three hearts, and then led a small club, finessing the jack on the return, so that B made the queen and the heart, and then established a club trick, getting in on the diamond to make it, and A making the ace of spades at the end.

Here is an example of the squeeze play built upon the opportunity given by the adversaries' mistakes. Only one player went game on Z's cards.

Z dealt and bid a spade, B two hearts and Y two spades. A led ace and another heart, B winning the second round, Z dropping the queen to conceal the jack. B led a small trump, and Z took out two rounds at once. Then he led the eight of diamonds and successfully finessed the jack, returning the ten of trumps, which B won with the queen, A discarding a diamond. Another heart put Z in the lead, A discarding the eight of clubs—too late to be of any use. Dummy discards a club.

It is now clear that A is keeping the queen of diamonds twice guarded, and has three clubs. To force him to discard one or other of those suits, Z plays the squeeze, by leading out both his remaining trumps. On the first A discards the small club, and dummy a club. Another trump and A lets go the king of clubs, hoping his partner has the jack. This makes it easy for Z to discard the small diamond from dummy and make two club tricks and two diamonds, winning the game with four odd.

The opportunity for the squeeze play in this case was given by several mistakes made by the adversaries, as they could have saved the game in several ways. In the first place, B's heart bid is very bad. If he does not call the hearts, A leads his club king and sets up the queen. Two hearts and a trump later save the game.

In the next place, after the initial error, B should have led the third round of hearts, trusting A to shut out dummy's ten of trumps; because if he cannot do so, the declarer has ace king jack, and will catch B's queen on a finesse. The false card of the heart queen should not have deceived B, as A would have followed the ace with the jack if he held it.

The third mistake was in discarding a diamond when B won the third round of trumps. That was the time to discard the encouraging eight of clubs, which would have saved the game by setting up a club trick immediately.

It is rather curious that none of the text-books give us this play, perhaps because it is rather too deep for the average person to see it. It is a very common experience for a player to sit and squirm around in what Henriques used to call "the agony of the discard"; but it is quite another thing for the declarer deliberately to put him in that position, knowing that he has to unguard something. In most cases the discard is forced unconsciously.

Answer to the May Problem

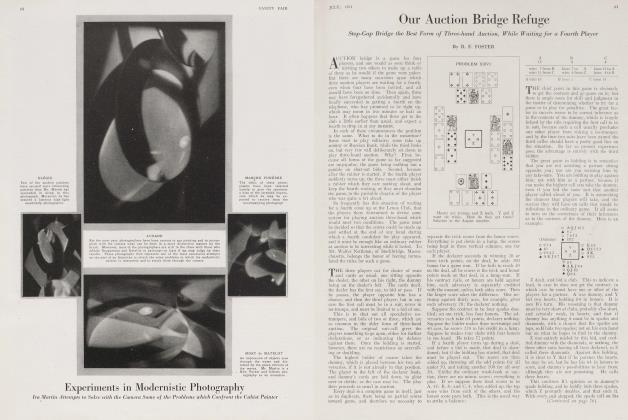

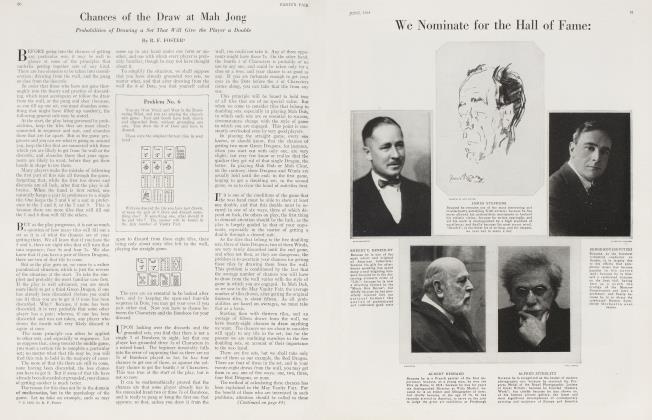

THIS was the distribution in Problem XXIV, one of Harry Boardman's best, and, needless to say, not an easy proposition to solve. Those who thought it could not be done had plenty of company.

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want five tricks. This is how they get them:

Z leads the spade king and follows with the queen of trumps. In the trump play, A wins the trump lead with the ace, and leads the king of diamonds, upon which Z discards the jack of spades, no matter what B does. If A leads another diamond, Y trumps it, and leads the club nine, still regardless of B's discards. Z wins whatever club B plays and pulls A's trump.

If A wins the queen of trumps and leads his remaining trump, Y wins it, and leads the nine of clubs. Z wins whatever B plays and leads the spade jack, which B wins with the queen. Now B must lose two club tricks.

If A refuses to win the queen of trumps, Z follows with the spade jack, and it does not matter what A and B do next, as the problem solves itself against this weak defense.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now