Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowCriticism and Contemporary Literature

The Need for a Critic Who Has Not Altogether Lost His Humour and His Zest for Life

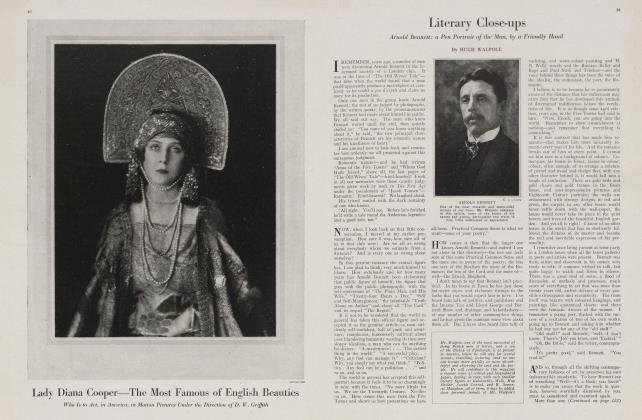

HUGH WALPOLE

LITERARY criticism in England has been, during all the war years, in abeyance. This was natural enough. It was almost impossible to consider literature as literature; there was literature and war literature, and the first of these two counted scarcely at all. People found refuge in books that had nothing to do with the war at all, but since these same books were hailed as an escape, it was probable that their literary qualities would be of very little importance to the reader. An interesting article might be written of our English war literature seen now in a very considerable retrospect, but it is enough to say here that a very little indeed seems to promise to be of permanent value.

In prose we can see, standing out like peaks above a very low range, such books as Masefield's Gallipoli, Brett Young's Marching on Tanga, Enid Bagnold's Diary Without Dates, and one or two more; our main expression found itself naturally in poetry, and there was, during the last three or four years of the war, such a flood of verse as English literature has rarely before seen. It became possible during those years for every young soldier with a love of literature to find expression, both of the glory and the horror of the event, in verse which the sudden eruption of vers libres made easier for him than he can originally have expected. Of the other war books, the histories, the military records, the accusation, the defensive, the appeals, and the protests, very little remains within the confines of literature. It will be the task of some Herculean commentator in future years to sift all these documents; their value will undoubtedly be great, but it will not, we can now pretty confidently say, be a literary value.

Of the English fiction produced by the war, there is scarcely anything that can pretend to a literary value. The most famous, if not the best, novel of the war was undoubtedly H. G. Wells' Mr. Britling Sees It Through, but as the years pass, the journalistic qualities that were seen by acute critics from the very beginning to mar that work, now become increasingly apparent. For the rest, there were Captain Brett Young's Crescent Moon, A. P. Herbert's novel about cowardice, and the lively, if vulgar, Peter Jackson of Mr. Gilbert Frankau. This is undoubtedly a very poor crop, but history is here only repeating itself; great works of art cannot be produced in the very centre of the crisis that inspires them, and perhaps in ten years' time from now, the masterpieces of the great war will begin to appear.

Criticism During the War

IT follows, therefore, from all of this, that the war had a very remarkable effect on English criticism. During the war, there was only one paper devoted entirely to literature and having a considerable influence, namely, The Times Literary Supplement. This paper, to which I will return in a moment, maintained a most admirable standard of justice and levelheadedness, but the other better critics of literature were, during the war, so deeply involved with politics that it was almost impossible to receive from them dispassionate judgment. This political bias increased a thousandfold after the Russian Revolution, when the war .changed, imperceptibly but inevitably, from an intellectual war to a class war. By the time of the Armistice, the critics were divided most definitely into young and old, and the older men such as Edmund Gosse, George Saintsbury, Professor Elton, Sir Walter Raleigh, and Clutton Brock, were in one camp, and the young men—J. C. Squire, T. S. Eliot, John Middleton Murry, and others—were in another.

The older critics had formed their judgment through many, many years of love of English literature. The traditions of that same literature seemed to them of immense importance, and although, in one or two cases, they may have been blinded by this love of the past to the real novelty and originality in new work, they nevertheless gave their readers a sense that they were delivering judgment on high standards, and that they knew the difference between art and pretence, however freshly coloured the second of those might be. The younger men, during the first years after the war, wrote continually as though nothing existed in new English literature except poetry; there came then, to redress this poetic balance, a little group of women critics headed by the brilliant Rebecca West, who camped on the field of the novel, and setting up their tents there, proceeded to portion out the ground to one another with little squeals of excited discovery'. It soon became the fact that most of the new poetry was reviewed by the poets themselves, and a great deal of the new fiction by the new women novelists.

The Clique as a Claque

THE danger of this became at once apparent, the gravest danger in all contemporary criticism, namely that of the dominance of the clique or the set. This became especially evident with the poets, because there were so many great generals of about the same power in the field that it was impossible that there should not be many rivals, with eager camp followers shouting "Hurrah" whenever their own individual officer secured a trophy. At one moment, for instance, Mr. Squire's Lily of Malud was the glory of the hour, and then suddenly Mr. Sassoon produced his Old Huntsman, The Sitwells sprang up with their eccentric publication Wheels, and round the corner there was the grave and dignified Mr. John Drinkwater, at whom the less traditional camps sneered until the success of Abraham Lincoln forced them to silence. Then there were the Imagists who poured scorn on all the Georgians; now these disputes would have mattered very little had not all the poets started to review one another's poems in the different papers of the day. However honest and open-minded a critic may desire to be, he must be a very, very exceptional Sir Galahad if he can perceive great merit in the works of a man who has only yesterday publicly declared that he considers Sir Galahad's poetry to be very worthless stuff.

The Georgians had been first in the field with their annual anthology and this gave an opportunity for all the later competitors, who had not been included in the aforesaid anthologies, to deride and sneer. Only two of the Georgians succeeded in keeping quite clear of all controversy, Mr. Walter De La Mare and Mr. Ralph Hodgson. Mr. Squire was forced definitely to choose some two years ago between the cultivation of his very original, if, rather unpoetic, muse and his very fine gift of criticism. He made his decision and became, first in the pages of Land & Water, then in the columns of the newspapers, finally as Editor of his own paper, The London Mercury, one of the principal critics of the day. In literature, however, as in everything else, you cannot have your cake and eat it, and while his position as poet has most certainly not been advanced during these years, his Olympian standard of criticism has provoked incessant opposition and has, unfortunately, done a great deal to increase the tendency towards cliques, as has already been noticed. Very rightly, he determined that his paper should be sternly judicial and should separate, once and for all, the ugly goats from the beautiful sheep. But the trouble of contemporary judgment is that goats and sheep herd round you too closely for any judgment to be truly final, and, if I may venture to say so, he made the mistake of surrounding himself too closely with men of his own colour. His own limitations as a critic had by this time become very apparent. Every critic has, of course, his definite limitations, but once the followers of Squire's criticism had been able to discover the directions in which his very strong sympathies lay, a great deal of the interest that there was in his criticism was cast away, and when his contributors all gallantly displayed their eager loyalty to their chief, it was difficult to feel that the judgments of The London Mercury had any longer any very general application. Then soon after the war, The London Mercury was faced with a very serious critical rival—the revived Athenaeum under the brilliant editorship of John Middleton Murry.

Mr. Murry vs. Mr. Squire

MR. MURRY had, of course, also his prejudices, but his ideals were so high and so manifestly honest and genuine, and the contributors to his paper were so brilliant (he had, during the two years of his editorship, the best musical critic, the best critic of contemporary fiction, and the best critic of foreign contemporary literature, writing anywhere in English) that it was impossible not to be profoundly interested in his paper. It soon became apparent that his views were very different from Mr. Squire's, and we had then the spectacle of two literary courts of judgment set up at the same time and in the same place, and differing upon almost every subject.

It followed from this that the influence of both papers was seriously hampered, and although The Times Literary Supplement kept an admirable balance and discretion through all this period and became indeed the only literary judgment that could definitely advance or hamper the success of a new literary work, it had not quite the young freshness and originality of these other two. There was also a new fault in this younger criticism. It was altogether too solemn and pontifical, so that the ordinary man who cared for literature and wished to know something about it gradually received the impression that the Best Literature was something altogether divorced from real life and something that could only be comprehended by very clever persons with a tweak in their system. Neither The London Mercury, until it made the happy discovery of Dr. Ethel Smyth, nor the Athenaeum, ever permitted themselves a smile, and for anyone to show a sign of good spirits or optimism ruled them out as men worthy of serious consideration.

Continued on page 92

Continued from page 40

A great gulf became fixed between the good and serious literature that hardly sold a copy, and the casual, careless literature that everyone was reading. At the same time the papers that the man in the street was accustomed to read gave up, almost entirely, any notice of literature at all. Paper was scarce, politics were all-engrossing, publishers had less money to pay for newspaper advertisements, and editors less money to pay for good criticism. Just before the war, there had been a movement to make contemporary literature something as entertaining for the ordinary man as football or horse-racing. Had the war not come, we might have returned under our own contemporary conditions to something like those days when men waited breathlessly for a new number of David Copper field or discussed eagerly the merits of a new Trollope. How possible this might have been has been already shown by the universal popularity of Masefield's Everlasting Mercy, of the interest shown by almost everybody in the novels of Arnold Bennett and Wells, and even in the large sale of so definitely literary a work of art as Conrad's Chance.

We have now to try and fight back something of that old position. It is of no use for Mr. Middleton Murry to write clever abuse of Arnold Bennett without any allusion to his magnificent giftSj it serves no purpose for Mr. Squire's reviewer of fiction to condemn month after month all the more interesting novels of the day without giving us at the same time some constructive criticism as well. High standards of criticism are one thing, and superior and very unhumourous patronage quite another; this does not mean that anyone wants the literature of the day to be received with indiscriminate praise. The trouble is that while almost all the more intelligent criticism is showing an increased remove from real life the other more commonplace criticism is casual, careless, and haphazard. There is, I believe, a public to-day who can discern quite clearly the worthlessness of careless praise, who needs at the same time some guide that it can respect, without at the same time feeling that it is being patronized and carried out of its natural element.

Where is the critic who, with real knowledge and love of books and a good, trenchant style at his back, will yet give signs of a sense of humour, of a love of proportion, and a good-hearted avoidance of small sets of current opinion? He must exist. There is magnificent room for a paper run on broad and human lines that will yet not be superior and over-pleased with its own intelligence. If such a paper and such a critic do not arrive, the divorce between criticism and real life will grow wider and wider. There is just now a pause; the poetical frenzy produced by the war is definitely over. There are few, if any, new novelists of any interest, but the time is coming when the real effect of the war on English literature will begin to be apparent. Where are the critics who will meet this new movement in an attitude of wisdom and true erudition, and at the same time in the spirit of human tolerance and sympathy ? Here is a chance for somebody to seize.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now