Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Proper Note of Passion

Concerning the Ardour and Technique of the Great Lovers in the Plays of the Month

HEYWOOD BROUN

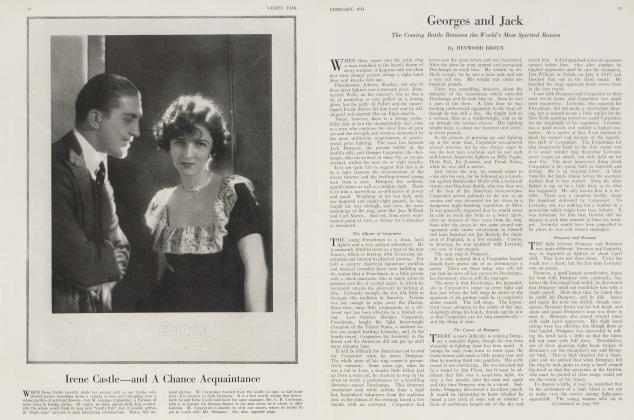

WHENEVER a critic wants to say something particularly annoying about an actor he thinks a long time and then writes, "Mr.

Wimpus gave an admirable performance in every respect save one. He lacks the proper note of passion." Such a notice makes Mr. Wimpus feel even worse than if somebody had charged him with lacking a sense of humour. There is nothing he can do about the accusation. He is not able either to affirm nor deny the rumour.

"Is that so!" seems to be the only rejoinder within his power.

From time to time we have availed ourself of the privilege of irritating Mr. Wimpus in this manner and also Miss Spriggles. It always works, but of late a certain uneasiness has crept into our mind. We are wondering just what we could say if the irate Miss Spriggles should suddenly confront us and demand, "Just what do you mean, sir, by 'the proper note of passion?'" As a matter of fact, we haven't the ghost of a notion. Probably, in so far as the assertion represents anything more than a mere desire to qualify praise, we mean that during the love scene in. which Miss Spriggles played we felt no desire to be the actor with whom she was associated. The fault for this state of affairs lies, as like as not, with us rather than with Miss Spriggles. An audience gets out of a love scene just about as much fervour as it puts in. If there is a chill about the scene it may be that it is the audience which lacks the proper note of passion.

For our part we never encounter a player roundly hailed as a great lover without wishing that he was just a little less efficient. It has been said that to play billiards well is the mark of a gentleman and to play too well the indication of a misspent youth. There is such a thing as making love too well.

For Love of Mary Stuart

ALL this may seem a digression from a review of plays of the month, but as a matter of fact most of the theatrical discussion which has come our way recently concerns the burning questions as to whether Clare Eames was sufficiently the great lover to play Mary Stuart and why the John Barrymore of Clair de Lune seemed a less thrilling wooer than the John Barrymore of The Jest.

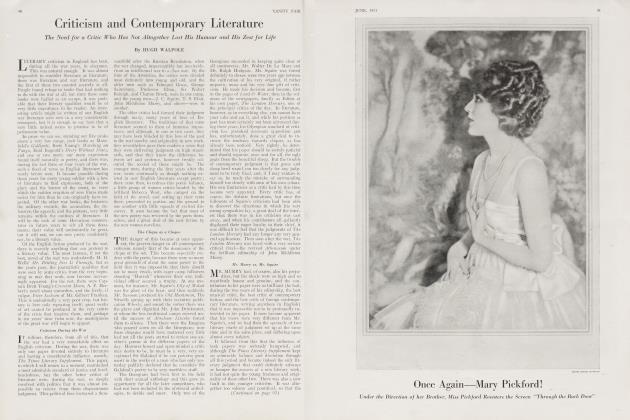

The handicap under which Miss Eames laboured was that a number of persons came to the theatre with a preconceived notion and picture of Mary Queen of Scots. The picture, we think, was influenced not a little by the two actresses who have succeeded in establishing and standardizing passion in the mind of the public. There was undoubtedly a demand that Mary Queen of Scots should be presented as a person something like the Carmen of Geraldine Farrar and the Cleopatra of Theda Bara. Clare Eames, who played the role, neglected either to hold a rose between her lips or to gaze at a man and blink her eyes very rapidly. Accordingly, she was set down in some quarters as a cold and bloodless miss who "lacked the proper note of passion." It is our contention that Miss Eames gave the most glamourous performance of the entire season. To be sure, she suffered no lack of praise. The one qualifying criticism was raised against her lovemaking. In this we are by no means ready to join. Far from thinking her ineffective in her love scenes it seemed to us that these were among the most persuasive moments in her performance. She seemed intense from the very fact that she played her scene with Bothwell without fluttering or panting but straightforwardly with her eyes open. She even kept a little humour about her which is no bad savour for lovemaking. In indicating tumult of the heart she did not find it necessary to make faces or turn somersaults. In spite of the prevailing modes and taste there is no reason on earth why a love scene should be confused with a bout at catch-as-catch-can wrestling.

As for the play itself, it seemed to us a gallant and stirring effort, once the clumsy prologue was out of the way. Undoubtedly Mr. Drinkwater touched upon a notion in this prologue, but he did not develop it far enough to catch the interest and it seemed to have precious little to do with the play which followed. It was particularly distracting from the fact that the prologue, though laid in Edinburgh, was set in modem times. When the curtain rose at the first performance of Mary Stuart upon a darkened room in which there sat a young man in a dinner coat your reviewer was flabbergasted and dismayed. "I know little enough about Mary Stuart," thought he, "but my ignorance is worse than I expected. I must have her mixed up with somebody else. For just a second I was thinking that she lived back in the days before dinner coats."

Bye and bye it was shown that she did and so a second process of readjustment was necessary. In the prologue, Drinkwater dealt with the problem of whether a woman's love might not be great enough to include two men. The older man in the scene, who was seeking to make the young husband come to his way of thinking, kept citing the case of Mary Stuart and presently the modern scene was gone and we were in Holy rood. Unfortunately, the old man seemed to have taken Mary's name in vain. Far from proving that a woman may love two men, the incidents in her life appeared to show that this particular great lover could not even find one worthy of her affection.

Only a brief moment in the life of Mary was shown in the play, but this seems to us the soundest method for biographical drama.

Since it is manifestly impossible in the theatre to present all the facts in the life of a man or woman, much the best method lies in making a virtue of this scantiness and focussing all the attention on one particular situation. After all, if you know enough about the thoughts and moods of a person in one given set of circumstances you know the person. The rest is a mere matter of cataloguing.

Mr. Drinkwater's Climax

THE incident chosen by Drinkwater seemed to us an interesting one, built, as it was, around a gorgeously contrived murder. Throughout the play one could sense this doom marching on, tiptoeing softly. There was no sense of the playwright's urging on his characters like a coxswain in an eight-oared race. It seemed almost as if he did not more than put them on their feet and turn them to the light with the command, "Now off with you." The figures, to be sure, were aided mightily in their chance to live by the players. One of the best casts of the season was assembled for Mary Stuart, for in addition to the brilliant work of Clare Eames there were excellent performances by Charles Waldron, and Frank Reicher. The fact that the play was comparatively unsuccessful does not detract from the fact that it was among the most notable productions of the season.

Continued on page 100

Continued, from page 29

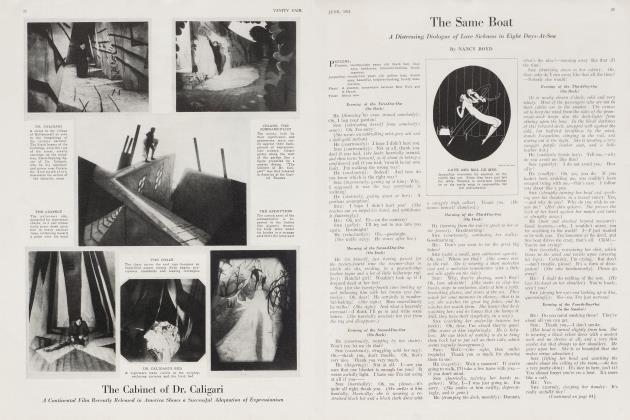

Of course good casts can't make indifferent plays anything else but indifferent plays. There was not the slightest difficulty in looking straight through two Barrymores in Clair de Lune and in detecting that nothing of much moment was going on behind them. To the credit of Michael Strange it should be said that she must have thought of her play first and her players later. Nothing in the role of the Queen suggested that it was written with Ethel Barrymore in view and in fact there was no urgent reason why John Barrymore should have been assigned to Gwymplane. He helped to make the first entrance exciting and also the scene in which he danced masked. It was interesting to wait in expectation of seeing the young star in hideous guise particularly if one remembered the fearful things he had managed to do to himself in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. But when he unmasked he didn't look half bad. His mouth was slit a little to be sure, but plenty of young juveniles in our theatre look just as terrifying without any makeup. After his introductory scene there did not seem very much for John Barrymore to do. In the big love scene he was cast merely as a loutish foil for the decadent duchess. As the late hero of The Jest, it seemed as if he might have been permitted to step forward when the scene was half done to exclaim, "Is that what you call decadent? Just give me room to pass and I'll show you."

Decadence with a Moral

THIS was not within the intent of the playwright. Indeed it is difficult to tell just what was. Seizing upon Hugo's L'Homme Qui Rit for an outline, Michael Strange has used it to point out that kind hearts are more than coronets. It is a decadent tale with a moral and the young playwright has not been willing to throw in her lot wholly with either element. During the scene which she has devised for the mountebank and the duchess she seems to have stirred up a working interest in decadence for its own sake, but once that scene is done, there is a relapse, or a revival as you will, to a scene quite literally in the mood of the death of Little Eva. John Barrymore did his best to bring a true tenderness to this portion of the play and succeeded, but it seemed decidedly a lesser note in his range.

For Ethel Barrymore there was even smaller opportunity. Her great gift for comedy, particularly that comedy which lies at the edge of things not so gay, was not even tapped. Little was required of her except that she should be queenly and beautiful, and this was obviously so easy for her that she can hardly expect to earn praise. As a matter of fact, the most arresting performance was that of Violet Kemble Cooper as the wicked duchess. At first she seemed to have no relish for the task which she was to perform. Few players have been so palpably pained as was Miss Cooper at the necessity of having her stockings removed in full view of the audience, but once that had been accomplished she warmed up to wickedness nicely. As far as the lovemaking went, she held John Barrymore in his place and allowed him to seem never any more than a collaborator and not always that.' It was a great privilege to see Miss Violet Kemble Cooper in a performance so striking that hereafter we shall have not the slightest difficulty in remembering her by it, for there are more Kemble Coopers than any other family in our theatre. No opening is complete without one and all are excellent. We have seen at least twenty Miss Kemble Coopers this year, although we are by no means certain that we may not have seen some of the same ones twice. For a time there was a movement among dramatic critics to have all Miss Kemble Coopers numbered so that they might be easily identified. That is no longer necessary. For the present the young actress in Clair de Lune is the Miss Kemble Cooper.

The Education of Mr. Thomas

FOR months and months one goes through a theatrical season feeling that he is frivolling away his time and then along comes Augustus Thomas with a new play. Education is the passion of Mr. Thomas, and the drama is merely a means for the distribution of his ideas. Thus, he wrote a melodrama a few seasons ago to acquaint the general public with the fundamental facts of hypnotism, and this time it is a finger-print tragedy designed to introduce psycho-analysis. Next season, we suppose, it will be a bedroom farce to popularize the theory of relativity. However, Nemesis is the play of the moment. For two acts it is almost wholly educational and then the plot begins and takes up so much of the playwright's time that he is unable to go on with his lessons. At such moments as Mr. Thomas is not intent on spreading a gospel he can write excellent and gripping dramatic dialogue. The court room act of Nemesis is one of the best things of the sort which our theatre has known. It is crisp, real and direct. Nothing else in the play is of much moment. Taking such familiar melodramatic figures as the young frivolous wife, the husband in the wholesale silk business and the attractive foreign sculptor, Mr. Thomas, has insisted that he is dealing with tragedy and has held the pace of his play to a deadmarch. The one vital piece of acting produced by Nemesis is the capital performance of John Craig as the prosecuting attorney.

Margaret Anglin's production of The Trial of Joan of Arc is beautiful and probably her performance is an admirable piece of acting. Our only complaint about the play is that, good or bad, there isn't much fun in it. Neither is there in the Macbeth of Walter Hampden, but in this case we are prepared to take a bolder stand and maintain that no good performance could possibly be so tiresome. The conventional production of Macbeth is apt to make a few of us captious critics sorry that we were not a little kinder to the Hopkins show while it was still alive.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now