Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now"Deburau" And The Others

HEYWOOD BROUN

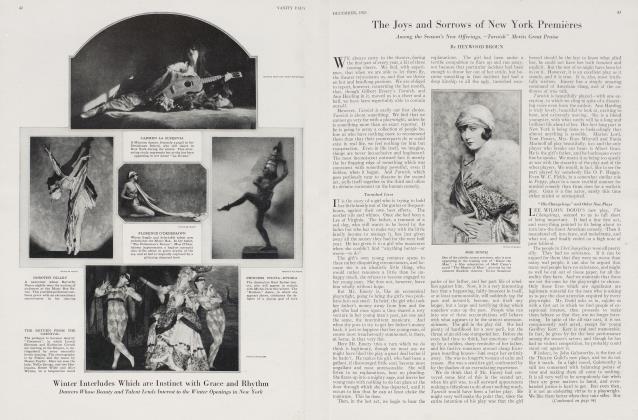

Drama Comes Out of the Kitchen and Wins a Place for the Play of Full Gestures and Emotions

THE theatre, it seems to me, has much in common with the game called tag. I haven't played it lately and it may be that in recent years there has been a meeting of the rules committee to revolutionize the sport, but, some years ago, it was conducted with two domains of safety, called hunks, on either side of the street, while all the territory between was dangerous ground, in which a player was exposed to capture and misfortune.

Just so there should be two hunks in the theatre. The dramatist may choose the side of the street in which all things crowd as close to reality as the stage will permit, or he may cross over into the land of lace and gesture, and verse, and round heroic phrases. Only he must make up his mind as to which is his hunk. He may not linger in the dangerous domain which belongs to neither.

From this point of view the two best plays recently seen in the theatre are Sacha Guitry's Deburau and St. John Ervine's Mixed Marriage. Each keeps pretty fairly to its own side of the street. The folk in Mixed Marriage talk as people do;'the characters in Deburau, as we should like to have them. Deburau, the great clown, is speaking to a press man about his early career in a travelling circus, and he says:

"The world was our tight rope. I sometimes see

In my dreams the whole world tented beneath the fold

Of the skies. And that old rope slung so high in air

That it stretches over sea and land. And, one by one,

Their figures black against a shining sun, My father, my brothers, my sisters, all silently, solemnly passing there."

In other words Deburau is a play in which no more than a reporter's question is sufficient to send an actor off into rhymed and metred eloquence. Now, as a matter of fact, I know perfectly well that interviews are not like that at all. If it were realistic drama, the actor would say: "Well, I certainly had 'em going tonight. What is it you want to know? Oh, yes, my early career. Well, I come from

one of the oldest families in St. Louis-."

Ervine, indeed, is such a steadfast realist that even murder and sudden death cannot move his characters to round talk. In John Ferguson the young lad went out to give himself up to the police for conviction and execution, remarking, "It looks like rain", while Mrs. Rainey in Mixed Marriage expresses her feeling that everything has gone to wrack and ruin by sitting down to darn socks.

Mr. Barker's Rhymes

THE virtue of the method employed by Sacha Guitry, and by Granville Barker, who has made the adaptation of Deburau into English, lies in its frankness. The audience knows from the beginning just which side of the street has been chosen for the play. No attempt is made to hide artificialities. They are invited to enter and take seats well up in front. If the long arm of coincidence, by any chance, thrusts itself into the action of the piece, nobody says "Shush! and attempts to overlook its presence. Instead, the author greets it boldly with a cheery "How-do-youdo" and rushes over to shake the thin hand of the long arm. In a prefatory note to the published edition of Deburau, Granville Barker admits, gleefully enough, that he has maintained Guitry's method of peppering the play with rhymes in order "that a certain amusing artificiality, even impertinence, of method might be added".

I must confess that there are moments in the rhyming of Granville Barker when I could do with a little less pepper and rather more oil.

"Pleasure seekers of Paris, you never need be at a

Loss for amusement while you have our theatre."

Such a rhyme burns the tongue, nor do I like Consianza and "tight-rope dancer". Then, too, there is the difficulty that verse is a medium to which the average actor in the modern theatre is quite unaccustomed. It renders him self-conscious. A rhymed couplet weighs on him like a mission in life. All the major players in Deburau were admirably free of this fault, but some of the minor figures were too intent on making the audience realize that they were in the presence of poetry and more particularly of rhyme. One would hear that something or other was "pretty thrifty" and then with all the strained attention of a man waiting for the other boot to fall, he would sit tense until the truth came out that it cost no more than "two francs fifty".

Verse was no such burden to Lionel Atwill. When Barker provided him with beautiful material such as the picture of Europe lying under the gigantic tightrope, he brought out its beauties. But he was never at a loss even when Mr. Barker's muse was in third speed. There were times when the adaptor seemed bent on tossing a succession of short rhymed couplets about the head of the actor as if he had been a much prized cane in a country fair booth. Atwill never wavered. Through good verse and poor he held a steady course, creating a character. It may be that all the great actors are dead, but in their absence I beg leave to make at least a temporary use of "great" for Atwill in Deburau. It is a performance of grace, humour, exceeding charm and fire. One or two critics have balked at this quality in Atwill and have expressed themselves in favour of a higher blaze. Personally, I prefer a limit to all conflagrations of the spirit. Where there's so much fire there's usually an equal amount of smoke. The meaning and the intent of it all becomes lost in the volume of vapour.

The passion of a player should be no greater than the compass of the theatre. In his moments of passion and of ardour Lionel Atwill did not shake the walls, but he conveyed an emotion completely and acutely. That is enough fire for anybody.

Belasco's Part in "Deburau"

DAVID BELASCO never for an instant loses sight of the mood of Deburau. In the past, Mr. Belasco has been concerned with productions on both sides of the street. He has done Heaven, and he has put upon his stage a Child's restaurant, complete to the ultimate and inevitable butter cake. Indeed, the charge was made at one time that Mr. Belasco's idea of fine staging was exactitude. In Deburau there is none of that. Everything is done with an eye to broad sweeping effects. There is the same flourish to the scenery that there is to the play and to the acting of Atwill. When it is helpful to single out one character from all the rest, Mr. Belasco promptly fades out the others behind a red gauze curtain and puts a spotlight on his hero. Some difficult stage problems requiring quick changes of sets Belasco solves shrewdly and expertly. And then he goes on beyond all expert things and shrewd ones to provide one or two pictures of definite and authentic beauty. I have seen by no means all the plays in the Belasco list, but Deburau is by all odds the finest production he has made in the last ten years.

As for the play itself, it certainly falls short of greatness. It has only a little of the sweep of Cyrano, with which it is comparable in form and mood. In Deburau there is a distinct period of slackness in mid-channel, but it recovers finely. The story of the great pantomimist, who lives long enough to fail in the theatre and long enough to watch his son step into his shoes, has moments of exalted eloquence. It needs no more for complete justification than the final scene in which Deburau watches with poignant joy the success of his son—and with aching heart, too,—as from the clamour of the applauding crowd there rises for the new man an old cry of "Deburau! Deburau 1"

(Continued on page 74)

(Continued from page 27)

"Mixed Marriage"

IN contrast, Ervine's Mixed. Marriage is laid in a worker's cottage in Belfast among folk who are humble though Irish. For three acts Ervine tells his story very simply and very truly, with a keen regard for a pointed and vivid dialogue which at the same time is true and human. His story is of an Irish Protestant who loves a Catholic lass against the wishes of his father, or "da", if you insist on accuracy. By the time the fourth act begins the problem of mixed marriage has become so complicated that Ervine can see no way out, so he summons an off stage mob and provides a chance bullet with which to kill his heroine. This is not playing fair. It dodges the problem and constitutes a confession of weakness on the part of the author. But, at any rate, Mixed Marriage is a seventy-five percent fine play, and Margaret Wycherly gives a one hundred percent performance as Mrs. Rainey.

Barrie's Mary Rose was a disappointment. He brought a clear-headed and hard-headed idea to the theatre, but, like his heroine, it strayed to some mysterious island and disappeared. Seemingly Barrie had it in mind to write a play to discourage the passion of his country for communication with the dead. In Mary Rose he seems to say that all affection is finite. Time is merciless. If the dead came back, they would find the living changed beyond all recognition. There is no use in blinking at the fact that death is a termination. It cannot be overlooked. To preach this lesson he hit upon the ingenious device of providing a strange island in the Hebrides upon which Mary Rose, his young heroine, disappears only to return twenty-five years later. She comes back exactly the person she was at the time of her disappearance.

She is not even conscious of the passing of time and she returns to a home in which age has been before her. She returns to a home which has forgotten her and has ceased to grieve. Here is the tragedy of the play. Here it should end, but Barrie has tacked on an incoherent last act in which Mary Rose has become a ghost and wanders about acting quaintly and allows herself to be called a "ghostie" and does other incomprehensible things. This particular act seemed to me to show Barrie in his most self-conscious fantastic mood. It is a most determined and persevering whimsy and it spoiled the evening. Nor was the earlier portion of the entertainment without its drawbacks. The idea of the play is excellent but it has been expanded beyond its substance. And likewise Miss Ruth Chatterton has been promoted to a realm beyond her scope.

Zona Gale turned her admirable novel Miss Lulu Bett into a play and something was lost in the process. It remained, however, an interesting but not altogether skilful use of material which was, in itself, fresh and well observed. Miss Gale by all means qualified as one of the most promising of native playwrights. Her play contains some of the most amusing dialogue of the season. The production served to prove that Caroll McComas could lift herself out of the ingenue class by the simple process of putting her mind to it and pulling her hair back. Louise Closser Hale was a gorgeous Grandma Bett.

Arthur Byron went to France for de Flers and Caillavet's Transplanting Jean, in which he cast himself as a gay boulevardier in his forties. It is rather the thing to say, whenever an American actor appears in a French play that he hasn't got the touch. It may be that Mr. Byron isn't very much like a boulevardier, but my own notions of the type are a little hazy. The discrepancy did not bother me in the least. At any rate, Byron is exceedingly amusing and Margaret Lawrence, his co-star, gives a dazzling performance. Transplanting Jean has a second act which is as funny as anything in town. The rest is not quite up to this standard, but it is good entertainment. Moreover, the play fills a distinct demand in any well-rounded season. It is the only play in town to suit the taste of those who like a little sophistication in their drama; a sophistication, we may add, a little deeper and more subtle than may be obtained by thrusting all the characters into a Turkish bath on ladies night.

"The Champion"

THE CHAMPION is a combination of The Man From Home and David and Goliath. Unfortunately the hero is English born, but Thomas Louden and A. E. Thomas have naturalized him and provided him with an extensive though rather shopworn equipment of American slang. The play is written largely for its second act, in which there is an amusing shift, whereby the despised and outcast hero comes suddenly into huge popularity. He had done no wrong. There was nothing against him, except the fact that under the name of Gunboat Williams he had won the lightweight championship of the world and defended it against all comers until his retirement. For this his straitlaced father ordered him out of the house, but at that moment in came an Earl, a Baron and a Marquis to shake him by the hand and capture him for weekend parties. Of course, after that everything was all right and he married the beautiful Lady Elizabeth. Grant Mitchell is easy and pleasing in the chief role and Miss Desiree Stempel sings Madelon just a little better than I have ever heard it sung before. It should be added that The Champion is not a musical comedy, but it is preposterous and pleasant enough to qualify as excellent material.

Cinderella is the theme which Guy Bolton has chosen for Stilly, and Florenz Ziegfeld has been wise enough to choose Marilynn Miller as the wearer of the glass slipper. Miss Miller adorns a slipper of any sort. Hers is the most joyous dancing New York has seen in years. Leon Errol seems to take equal pleasure in falling. Jerome Kern has done a tuneful book and Urban has been both brave and discreet in his use of colors. On all counts Sally deserves an enthusiastic recommendation. In spite of the fact that it is the best sort of fun, it really is an achievement in all the arts which concern the eye.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now