Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSome Newcomers—Literature and the Drama

In Which It Is Shown that England Has No Great Reason To Be Pessimistic Over the Future of the Arts

HUGH WALPOLE

I AM continually asked by my American friends as to who are the new personalities in books and the theatre and music, and by these questions they do not generally mean the accepted reputations. To such inquiries it would, for instance, be foolish to give the names of Sheila Kaye Smith, Francis Brett Young, Fay Compton and John Middleton Murray, all of whom have arrived in the last six or seven years, and whose names must be well known to anyone in America who follows such matters with curiosity.

The names of the very last year or two are more difficult to determine, because there is nothing so fallacious as the sudden first successes of a writer or an actress.

Some young lady, for instance, with a pretty face and a dimple in her cheek has a flapper part in a modern comedy which she plays successfully because she has only to be her sweet, most naturally unnatural self. The next day the illustrated papers are full of her; she is invited to the houses of Prime Ministers. A year later she makes a sentimental marriage, and a year after that there are twins. The real test comes when after the twins she is given some really difficult part to play. Then, if she can play it, it is time to consider her seriously.

And in Poetry, how many bubble reputations were made by the war? Some young man went to France, discovered that war was horrible, that people were blown to pieces, that the trenches were full of mud, that the Commanders in Chief were elderly men, and that a lot of people were still staying at home; and he described all these things in lines that would have been jouxpalism had they not been cut into irregular lengths. His day is over and gone, and nobody very deeply regrets it.

Promise—Twenty Years Later

WITH the Novelist, too, it is extremely easy to make a splash at your first attempt. Your personality is fresh to the world, a little different from other personalities, and everyone is delighted to greet it. Whether you will really ever do anything with that personality is a question to be answered twenty years later.

And so in this estimation of quite new personalities, one must reckon promise even more strongly than faults, and the few names that I have here selected will, it seems to me, granted life, luck, perseverance and not too much early success, undoubtedly matter in the intellectual life of England ten years from today.

In the theatre I must admit that in spite of a rather wailing article that I wrote for this paper a month or two ago there are a number of most interesting new personalities.

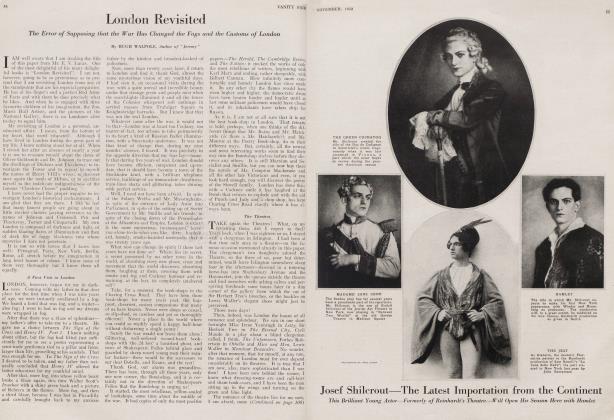

If an American were to come to London tomorrow and to say to me, "I have just a fortnight here and I have come for the acting rather than the play; I have not been in London for three years, but before that I came continually; whom would you suggest that I should see"? I would give him these names—Jack Hulbert, Ernest Thesiger, Meggie Albanesi, Nicholas Hannen, J. H. Roberts and Edith Evans.

It would be noticed that only two of these are ladies, and we are, I think, badly in need of new actresses just now.

Miss Evans has been condemned to play a

series of elderly, spikey females, and her talent,

I suspect, goes a long way beyond these admirable, cynical portraits.

Miss Albanesi (the daughter of Madame Albanesi, the novelist) is, I think, with Miss Kathleen Nesbitt by far the ablest of our younger, intellectual actresses. She has won her position, at present, chiefly by a reserve force in such plays as The Skin Game and Loyalties, and it has yet to be seen how great emotionally she can be when she lets herself go. She is full of personality and, when she is on the stage it is very difficult to pay attention to anybody else. She has a delightful voice and great repose in all her movements. She is the least fussy actress we have, and she is admirable in quiet and significant dialogue. It is not to be denied that a younger emotional actress of real tragic force we do not seem, at present, to have.

The Versatile Thesiger

MISS Phyllis Nielson Terry, who might have been that actress, was, in my opinion, dreadfully disappointing on her return to London in Fagan's play, The Wheel. She moves automatically; she is full of theatrical mannerisms, and it is hard to believe that this is the actress who ten years ago startled the London world in her wonderful performance in a Twelfth Night matinee.

Of the men I have mentioned, Ernest Thesiger has the most striking personality, and Nicholas Hannen is the best all-round actor. Hannen, indeed, is, some of us think, with Basil Rathbone, who is now, I am delighted to hear, winning such a success in New York, by far the best actor we have had of late years. He has done recently a multitude of parts, acting in McDermott's Everymans Theatre at Hampstead, but he did not really make his name in London until his performance of the Blind Officer in Pinero's ill-fated play, The Enchanted Cottage. No one who saw that performance will ever forget it—the pathos of it, the sincerity and the beautiful rightness in its atmosphere. But I had seen him just before that in several small parts at the Little Theatre. He there showed great versatility and also much creative power, adding, as an actor ought to do, his own spirit of creation to the author's, merging it with the author's, and I was astonished that he was not snapped up by every manager in London. Well, now since Pinero's play, he has been snapped up, and his future is quite assured.

There are a thousand parts one would like to see him play, and he would be good, I fancy, in almost anything, but he has that dangerous quality of charm which now that it has been discovered will undoubtedly lead many people to its determined exploitation. If he can resist that, he will be a great actor.

It would be impossible to deny Ernest Thesiger's versatility. It is astonishing what, with his so pronounced personality, he is able to do. He made his name after returning wounded from the front in the early years of the war, in a ridiculous and imbecile farce, A Little Bit of Fluff. He played this, I believe, for more than two years, which would have been quite enough, one would fancy, to destroy

anybody's talent, and then he startled us witli his admirable tenderness in the part of the Scotchman in Barries' Mary Rose. He was less well suited in Maugham's Circle. He again becomes most notable in Galsworthy's Pigeon at the Court Theatre. He had there a most difficult part, not quite realised, I think, by the author, certainly not quite given to us completely in earlier representations of it, and he put that final touch to it, as the artist should, and made it a convincing thing. His appearance is bizarre, and there are, of course, many parts in which he could not be well suited, but his intelligence is acute and he has an astonishing gift of adding poetry to all that he has to do. Even the most futile farce becomes something a little better when he touches it.

I should like to see him play Iago and Richard the Third and the Fool in King Lear and many other things. He is old enough and wise enough to know just what he is about; he is talented in all sorts of ways: a painter of no mean repute, an admirable musician, one of the best mimics London has ever seen, and, finally, he is unlike anyone else at all. He has certainly a great future.

I have left to the last, Jack Hulbert, who is a droll, maintaining with Nelson Keys, W. H. Berry and Leslie Henson the standard of vaudeville in London. He has not Keys' wit, nor Berry's bohemianism, nor Henson's grotesquerie, but he has an exact knowledge of what he can do, a most excellent sense of humour and dancing genius, and best of all a conviction that this is a splendid world in which to be alive, that he wishes no one any ill, and that he is your best friend. I do not know why it is, but in vaudeville buffoonery leads often to a kind of implied ill nature.

Hulbert as a Genial Comedian

EORGE ROBEY has been ruined by this, and often Berry, the most genial of all our comedians, suggests a little nowadays that he despises his fellow human beings, but Hulbert loves us all. His smile is one of the most famous things in London.

When he does for us a little sketch of a man who is anxious to be at his best, because he is hoping to obtain a good job from a relation and is at the critical moment tormented by a hiccup, we do not laugh at the man in irony, we laugh with him because we feel as though we ourselves were in his position. Hulbert's bewildered, appealing look at his wife, begging her to help him, is an appeal to all of us. We know that we are of the same clay. There is a kind of implied humility in Hulbert's talent which is intensely attractive.

I doubt whether he will ever make an actor in what is known as the legitimate. I saw him play Cyril Maude's part in Lord Richard in the Pantry, and he was not a success. One felt that he needed freedom; he has just too much irresponsibility to tie himself down to another's limits. But he has the opportunity, I think, of raising vaudeville in London into something more delicate than it has hitherto been.

There are personalities on the English stage today, plenty of them. I am already recovering, you will see, from the pessimism of a month or two ago.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now