Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowConcerning the Importance of Defensive Play

"What Boots It at One Gate to Make Defence and at Another to Let in the Foe"

R. F. FOSTER

Do you know, Mr. Crytisky, I cannot understand why it is that I always lose at bridge. I have read all the books, and taken lots of lessons, and I know all the conventions by heart."

"Really, Mrs. Booksparrow, I thought you were considered a very good player. In what part of the game do you fail?"

"I am sure I don't know. It is not in finessing or making reentries, or ducking, or letting dummy ruff, or anything of that sort. You are such a good critic, I wish you would play with me some time, and tell me just what is the matter."

"Gladly, I am sure. You know that handsome man with the dark complexion that you ladies always call the Sheik. Well, he asked me to get a fourth for a rubber with Mrs. Jeroleman-Smith this evening. Suppose we try them."

"That would be lovely. So her name is Jeroleman-Smith, is it? We always call her Mrs. Hyphen-Smith for short. I don't wonder she uses a handle to her name. I should if I were born just plain Smith."

A set match for six rubbers being agreed upon, Mrs. Booksparrow found the Sheik seated on her left. "Now be sure and tell me any mistakes I make, partner," she urged Mr. Crytisky.

"After the hand is over, if I see anything, I'll speak of it if our adversaries will permit."

"Go ahead," granted the Sheik blithely. "We might all learn something,"—a suggestion that did not seem to please Mrs. HyphenSmith. She rather supposed herself to be above instruction, having played for ten cents a point upon one occasion.

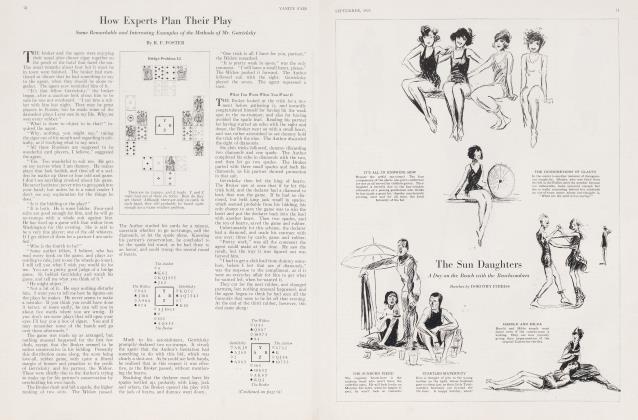

Nothing happened for the first deal or two. but on the rubber game this distribution was the result of Mrs. Hyphen-Smith's dealing:

The opening bid was no-trump, the Sheik taking it out with two spades. Mr. Crytisky led a small diamond. After some consideration a small card from dummy allowed the queen to win. The ace and another heart followed, dummy trumping the king. The ace of diamonds gave the Sheik a club discard, and a club lead allowed him to trump the king.

Another heart was trumped, and another club led, upon which Mrs. Booksparrow got rid of her losing diamond. Another heart was won by dummy's last trump, and another club was led. This was trumped second hand with the ten, the Sheik discarding his last heart, after which he made two of his remaining trumps, winning the game and rubber.

"I don't see how we could have helped that, partner," remarked Mr. Crytisky. "Very clever play that passing up the first trick, and then getting the club discard to establish the cross ruff."

"I think I could point out a little mistake if you will allow me," suggested the Sheik, turning to Mrs. Booksparrow. "You had two chances to save that rubber. If you trump the second club with the ten and lead the ace, you kill dummy's king of trumps and make a heart trick. Even after you have missed that chance, if you do not trump the third club but discard vour heart, you must make all four of your "trumps, as you can count me for only three left if you let me trump."

On the third game of the third rubber, this hand come along, the Sheik dealing:

The dealer's bid was no-trump, all passing; and the opening lead was the deuce of hearts,

the ten winning. Mrs. Booksparrow won the club finesse with the king, and returned the heart, her partner letting the king win. Four spade tricks followed, on the last of which Mrs. Booksparrow discarded a diamond, her partner a club, dummy a heart. The Sheik led another club, and ducked it when the second hand renounced, Mrs. Booksparrow winning with the eight.

The king of diamonds was allowed to hold. The jack was won by the ace, and another diamond allowed the queen to win, but forced the loss of two club tricks and the rubber.

"Nothing wrong about that, was there, partner?" inquired Mrs. Booksparrow.

"Your partner certainly did his best for you in refusing to put up his ace on your return of the heart," remarked the Sheik, smiling.

"Then everything was all right? You know, I have read so many books on bridge, I know all the rules by heart."

"If you will pardon me," suggested the Sheik, "I think if you would forget the books for a while and read the hands, you would do better.

"Your partner led a small heart, so he cannot have held ace-queen-jack. You and dummy have all the top clubs between you. To bid no-trumps, I must have the ace of spades therefore your partner has no reentry. But you have, and if you switch to the diamonds instead of returning the heart, all I can make is the odd trick."

Mrs. Booksparrow smiled at her partner rather dubiously for a moment, and then ventured to remark, "The weak part of my game seems to be the defence, doesn't it?"

Mr. Crytisky could only smile, and say, "Never mind. We shall probably do better next time. We are all learning something.''

On what proved to be the last hand of the last rubber, after having lost three of the five played, Mrs. Booksparrow dealt.

The dealer passed, and the Sheik bid notrump. The opening lead was the deuce of spades, the seven, queen and ace falling. Four rounds of diamonds followed, the Sheik discarding two clubs, Mr. Crytisky the eight of clubs and one of each of the other suits.

In order to avoid making the spade jack a reentry, Mrs. Booksparrow led the nine of clubs to top dummy's seven. The Sheik put on the ace and led a small spade, forcing the king. The return of the club went to the king, and another spade put dummy in to make the rest of the diamonds, after which the ace of hearts netted four by cards and the rubber.

Continued on page 86

Continued from page 71

"Well now, that hand was certainly hopeless, was it not?" said Mrs. Booksparrow smiling at the Sheik.

"Well, as Charles Dana used to say, 'First you tell me a story, and then you ask me a question.' No, the game was not hopeless. In fact, you would undoubtedly have caught me napping."

"Really?" smiled Mrs. Booksparrow, while Mrs. Hyphen-Smith turned to Mr. Crytisky with a look which clearly indicated that such a thing was impossible.

"I think," explained the Sheik, "if you consider the development on the very first trick, you must see that as I bid no-trump and had absolutely nothing in diamonds, I must have had either the ace or king of spades. The only possible reentry for the diamonds, which you stopped, was the queen of hearts or jack of spades. You could have killed the heart queen. You could also have killed the jack of spades, if you had not played the queen."

"But dummy's seven would have held the trick."

"Quite true; but that docs not bring in the two small diamonds that won the game. Three diamonds, two clubs, two spades and the ace of hearts was all I Could have gotten out of it, unless—" and the Sheik smiled at his partner.

"Unless what?" demanded Mrs. Booksparrow.

"Unless I had taken no chances of the diamonds falling in three leads, and had started with a small one, giving you the first trick at once. The distribution would have been highly improbable."

"Well, I would never have dreamed of such a thing," Mrs. Booksparrow assured him. "Fancy leading a small diamond from six to the ace-king-queen, when you have two yourself. Did you ever hear of such a thing?" glancing at Mrs. Hyphen-Smith.

"Well, my dear, we play it that way all the time in our club at home; but, of course, we are all advanced players."

THHERE was a rather amusing tilt between two bridge players at Pinehurst last Spring, each of whom had been accusing the other of a strong tendency to overbid the hands. Having cut as partners in one rubber, one of them had the deal and bid a diamond, second hand a spade, the dealer's partner two hearts, fourth hand going to two spades.

The dealer dropped the diamonds and supported the hearts, bidding three. The second hand advanced the spades to three, the two next players passing. The dealer, apparently rather put out at his partner's abandoning the hearts, went back to the diamonds, bidding four, which was promptly overcalled with four spades. This brought the dealer's partner to life again with five diamonds.

Fourth hand and dealer passing, the original spade bidder doubled. When this came round to the dealer, he redoubled, the second hand being content. The dealer's partner now began to think he had been a bit hasty with that five-diamond bid, as they might easily go down two tricks, for 400, there being at least five losing cards in his hand.

But he figured that if he went to five hearts, even if he went down three tricks, he would not redouble, and that would mean a loss of only 300, instead of 400. Accordingly he went to five hearts, and the spade hand doubled, as he anticipated he would, but he did not redouble.

The dealer meanwhile, had been figuring along much the same lines, and thought that if he were to go to six diamonds, after having redoubled the bid of five, he would be left to play

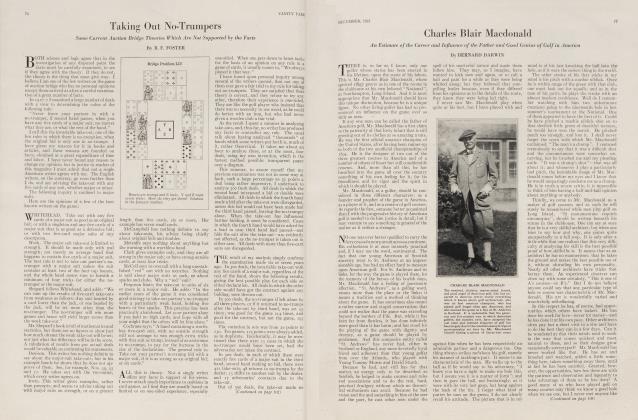

it undoubled, and even if he went down 150, that would be much better than he" ing set 300 or 400 at hearts.In this assumption that six diamonds would not be doubled, he was entirely correct, and the hand was played at six diamonds undoubled. This was the distribution

As will readily be seen, it is a little slam, no matter what the spade hand leads. Had the redouble of five diamonds been left in, the dealer would have scored 453 points, instead of only 127. Had the double of five hearts been left in, the dealer's partner would have made a little slam and scored 278 points. If he had redoubled and been left in 474 points.

Answer to the July Problem

THIS was the distribution in Problem XXXVIII, one of Frank Busser's compositions, which are always interest, ing.

There are no trumps and Z is in the lead. Y and Z want seven tricks. This is how they get them:

Z leads a spade. If A wins it, Y discards a small club and B a diamond. The problem is now practically solved, because no matter what A leads, Z wins the trick and leads his good spade, Y discarding another club. No matter what B discards, he is lost. This variation is fairly obvious.

If A anticipates this by leading the spade himself for the second trick, Y and B both discard diamonds; because if B sheds a heart instead of another diamond, Z will at once lead a heart, and on the third round of hearts will adjust his discard to B's, who must unguard the clubs or the diamonds.

But, if A refuses to win the first trick, Z must shift to the ace of clubs and follow with the three, putting B into the lead before Y is obliged to unguard the ten of clubs. B is now in difficulties. If he leads a diamond, Z puts on the ace and leads the jack of clubs, forcing a discard from B, who must either establish the five of diamonds for Z, or the deuce of hearts for Y, while the ace of spades dies.

In this variation, the better defence for B is to lead one of his top hearts after winning the second club lead, A discarding a spade. Now comes the nub of the problem. Y must lead another winning heart immediately, so as to allow Z to get rid of the jack of clubs. This clears the way for Y's ten, and B's discard on the ten of clubs solves the problem, as Z will throw off the losing spade in any case.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now