Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowStephen, Henry, and the Hat

A Frivolous Excursion in Biography Introducing Hitherto Unmentioned Stories by Crane and James

THOMAS BEER

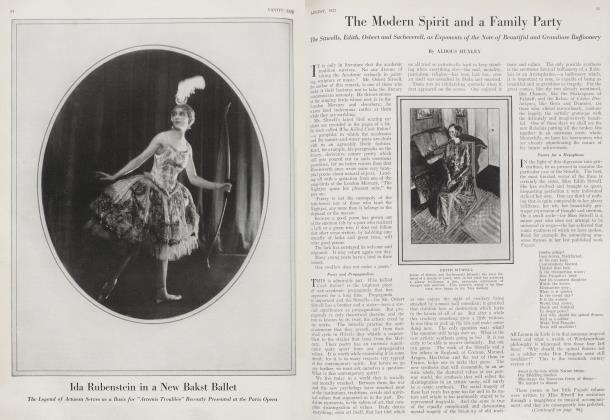

TWENTY-FIVE years ago, a middle-aged gentleman of fine perceptions turned into Brown's Hotel from the dim slope of nover Street. He wore a silk hat. The hour as late, so I assume that his other garments ere such as would be worn by middle-aged gentlemen of fine perceptions going to sup with ing but correct, compatriots in Brown's Hotel, But the hat is History. He passed upstairs; he knocked at the door of a parlor; he went in . . . Courage and impudence collapse. Let History, aided by the Alphabet, carry on.

"I was aralyzed. I had forgotten all about asking him to supper. He walked in. Harold Frederic was trying to play the piano. Z . . . was singing one of her French songs. X . . . was asleep on the floor. Stephen Crane was the only strictly sober person in the room. Mr. James was pretty disgusted but he went into a comer with Stephen, and they sat and talked about style. . . . Then Z . . . began to make love to Mr. James who seemed scared to death of her. Harold Frederic went home to bed. Z ... got worse and worse. She finished things up by pouring champagne into Mr. James's silk hat. So Stephen took her downstairs and put her in a cab. It was awful."

Thus to revisit a parlor in Brown's Hotel, twenty-five years ago, is not quite civil. But earth embraces all those bodies, now, and the awful scene has no survivor unless some waiter drags out a life of sorts in Putney . . . whither go all waiters on retirement. I don't know what Z . . . "half Greek, half French, the dragon fly—" was wearing and how X ... happened to be asleep on the floor, or what happened to the hat after its bath of champagne, or w7hat happened to my historian when he got back to Boston and his father read this diary. But the boy had a valet, and the fellow, I trust, did something kindly to the hat. And, perhaps, Mr. James went on talking style in letters to Stephen Crane after the slim young man came upstairs, having put Z . . . in a cab. But, three years later, Henry James wrote: "My relation to Crane was—

I am happy in thinking—unblemished in cordiality. The difference in our ranges of habit and experience was terrific. He had many admirable qualities, but he had lived with violence."

The Violence of Crane

WITH violence! But how else could the master of groomed circumstance appraise a man who met everything headlong and shrank from nothing? He was not yet twenty.seven years old when he talked style with Mr. James in the corner. He had escaped from a foundering ship in the tropics. He had seen men shoot each other, not from animosity but to maintain a reputation for good marksmanship. He had tossed his last cent to a homesick runaway on the Plaza of San Antonio, and so reduced himself to the unkempt society of retired sheep herders in a Mexican sty. He had strolled across the track before a speeding locomotive "to see how scared I'd be", and would presently stroll into a spatter of Spanish bullets to examine that sensation.

He would die in his thirtieth year. His fame was at its height. The Red Badge of Courage and The Open Boat were everywhere.

A Bishop had publicly denounced Maggie as obscene. The New Review had uttered long _ praises of the boy's queer tales. He "knew little of literature, either of his own country or of any other, but he was himself a wonderful artist in words," . Joseph Conrad says. "His impressionism of phrase went really deeper than the surface ... he was very sure of his effects. ... Yet it often seemed to me that he was but half aware of the exceptional quality of his achievement." He talked very little of his work, save when pressed, and then he talked in slang, rather often. He called his free verses "pills" and his tales "my stuff". He wrote to his best friend, "I know that my work does not amount to a string of dried beans." Henry James was astonished. Yet their fate in letters was almost identical.

Coloured Letters

SOME earnest young priest on duty at Saint Henry's shrine is now preparing to hurl a sacred utensil at me. Henry James—hasn't Mr. Conrad said so?—was the historian of fine consciences and that is what we want, if letters are to amount to anything. And Stephen Crane has been damned beside the academic Charles as a cheap writer for Puck.

. . . True, he never wrote for Puck but it was a good professorial description. He wrote of scared young recruits in battles and ruined girls of the Bowery and such cattle. So my comparison is at once odious and impertinent. Yet their fate in letters was almost identical.

It seems that there are only two attitudes possible in judgment of Henry James. I find both insupportably vulgar. If it is asinine to call the author of The Wings of the Dove a tinter of fans, it is also asinine to call him "the sole Master of expression in the English language since the death of Swift". I wonder ... do the priests and acolytes quite understand the harm done to their saint's reputation by such babble? Some eventual and unsentimental biographer will—I hope—tell us the reasons of the man's retirement into that sunny, hedged garden. But inside his vegetable parapet he brought to blossom So many flowers beside amenity's golden rose! If he recoiled from kine and journalists and outrageous females who filled his hat with champagne, it is not our business. If he is to be horsewhipped for the limits of his vision, why, in the name of the remnant of justice, let us crucify Max Beerbohm for his failures as a marine painter and crush Aldous Huxley's skull on the strange altar-of Ethel Dell!

So has the art of Stephen Crane. It was their adjoined fate that lesser men have imitated everything in their equipment save that essential, the point of view. The figure of James is surrounded by a haze of appreciations, biographical sketches, the efflorescence of his kind activity in the area of literary production. Crane is so far forgotten that he has left, by way of prominent admirers, no one to speak of save Mr. Conrad, Mr. Bennett, Mr. Wells, Mr. Hueffer, Mr. Mencken, Mr. Tarkington, Mr. Vincent Starred . . . in other words, artists and critics who are artists themselves. He is that pathetic shape, a writer's writer. Miss Cather thinks it criminal that his three best tales aren't taught in colleges and the "best paid" she author in this meritorious land lately asked if anyone had ever heard of a man named Stephen Crane . . . "because I stumbled on a book of his called George's Mother, and it really isn't bad. . . ."

Since one has recklessly said that his art coloured letters, one had best offer some proof. He wrote a staccato, nervous prose with selected adjectives placed in a manner that astonished Henry James. His pictures are etched so starkly that they persevere in the mind rather as outlines than as completed effects. For that reason they occur again and again, unconsciously stolen by writers who have no thought of theft. I select, painlessly, some examples. These are chosen in every case from the recent work of well known people, original people and people—one believes —above pilfering. In a late English novel: "High in the sky soared an unassuming little moon, faintly silver." Crane's version was, "High in the sky soared an unassuming moon, faintly silver," in 1899. From another and wildly admired English novel: "Valiant noise was made on a platform in one end of the smoky hall by an orchestra. The players seemed to have happened in by accident from nowhere." In Crane's Maggie (page 112): "Valiant noise was made on a stage at the end of the hall by an orchestra composed of men who looked as if they had Just happened in." The new writer's mind, you see, has retained the striking adjective that begins the sentence and has split the effect. In a late American tale: "The solemn smell of frying parsnips came from the kitchen." In Crane's Whilomville Stories the Angel Child and Jimmie Trescott threw parsnips into the furnace and the house was filled with "the solemn odor of burning parsnips." (Go, burn a parsnip, if you wish to learn how right he wras about the result!) Sometimes he perseveres by a mere suggested image. In The Red Badge of Courage you will find a dying man who lurches from the rout and inscrutably halts . . . "He was waiting with patience for something that he had come to meet. He was at the rendezvous ..." with death, of course.

The Sardonic Emphasis

THESE effects, I admit, are superficial. The mind back of his few tales has not appeared again in our letters. The decade that found Mr. James emasculate and tedious, found Crane bewildering and curt. He had little sentiment. His The Blue Hotel and The Monster reduce human sympathy and human will to spots on the map of accident. He had Chekhov's preference for viewing action through the eyes of dullards and much of his best work is contained in brief sketches. He wasn't radical, but his posture before American respectability was painfully that of a small boy with a brick in hand. He rapped the surface of our life with lean and careless fingers, noting its rotten hollows without repulsion and without tears,, with a sardonic emphasis that repelled inferior folk. He had no reverence.

Continued on page 88

Continued from page 63

He wrote of a great English hostess that "her conversation is dull as a courtesan's," of a famous female author that, "she has no more mind than a President," of a tea party at Saint Henry's that, "God knows how James stands these bores who pester him!. It was stupid as an argument on the immortal soul." He had, you see, lived with violence.

Mr. Amory Blaine has put at my disposal two unpublished tales which display the essence of these authors. Crystalline is too long for quotation. I give a synopsis. Lord John came into the drawing room at Breen after dinner and, sotto voce, told Mrs. Dawlish —"that smart bonnet on the bust of Diana"—how Edwin Totteridge had put the men in a roar over their port by chaffing Mr. Vervain about a hat. Priscilla Belden couldn't quite hear what happened to the hat—she was not, in any case, really listening to Lord John's tattle—but she began to recoil from Totteridge. What follows is set forth inimitably with a consummate mastery of all implications. One reads of Priscilla's spiritual flight from Totteridge who would—no, could—chaff Mr. Vervain about a hat before a crowd of men after dinner. One reads of Totteridge's perplexity. He had chaffed Mr. Vervain about the hat because—his perceptions, you see, had limits—he thought it rather funny that a woman had spilled champagne into Mr. Vervain's hat. He was that sort of young man. And one reads how that Mrs. Dawlish tried to interfere on Totteridge's behalf and how she didn't help things in five pages of prose as delicate but as clear as Venetian lace. This is a battle of perfumes above a shaven lawn. One reads, too, of Lord John's perceptual anguish on hearing that he'd upset Priscilla's estimate of Totteridge, and one reads how, when the brougham was carrying Priscilla to the station, next morning, Mrs. Dawlish put a period to her musings on the matter by saying, "Oh . . . but—! Poor dear!"

Crane's effort is only seven pages long. It is called, frankly, The Hat. Pete was the assistant coachman of a rich bachelor. One night, the head coachman sent him to bring their master home from a house in Forty-Sixth Street. You are told how blue the Ave-

nue was as Pete drove up its still stretches and how a girl glanced at his white buckskins and how proudly he sat on the box, outside the lit window! and how uncertainly his master came down the steps and how, when Pete helped him out at his own house he gave Pete his silk hat which "shed into the chilled air an abrupt scent of wine," And Pete was frightened because he'H promised his mother in New Hampshir that he wouldn't take service with men who drank . . . All night, his promise dogged him about his bedroom as he tramped, and his morals wrestled in the empty passages of his brain. The moon lit the cup of the upturned hat on his dresser, and the stained silk of the lining was an obscene, winking eye. He woke the head coachman to ask advice and the fellow said, "Aw, d'hell!" and went to sleep again. And at dawn, the daisies of the wall paper were great ants that loathsomely crawled on the boy's mind. So he gave up his job . . . Twenty cold days later, his jacket buttoned across his naked chest, he walked through a blue night into' the dimness of a last block. The windows of the tall buildings were closed like sleeping eyes. Afar off the lamps of the avenue glittered as if from some unapproachable, warm heaven. Glasses tinkled behind the jewelled gates of a saloon with a noise of merriment He halted on a dock. A hidden factory again sent up a glare that lit for a moment the water's oily motion below his feet. . . . When they brought the news to his mother in New Hampshire, she went on feeding the turkeys. Nothing disturbed her face's arid gravity. But, after a while, her husband found her sitting behind the grape arbor and she said, "John, that boy must have took to drinkin' whisky and lost his work! And after I'd prayed an' prayed to God that he'd keep to a Christian life!"

"Emmy," said her husband, "the boy's dead. He's dead, Emmy, an' you got to fergive him."

Vehement tears were encased in the deep wrinkles of her cheeks. She clasped her hands on the bony hummock of a knee and moaned, "Oh, yes! I fergive him!" The expiring sun was glued upon the sky like a wafer and its light created on her face the glow of a forgotten, charming girlhood.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now