Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA Backward Glance at America

Thoughts on Change and on Everything, Fifty Years Hence

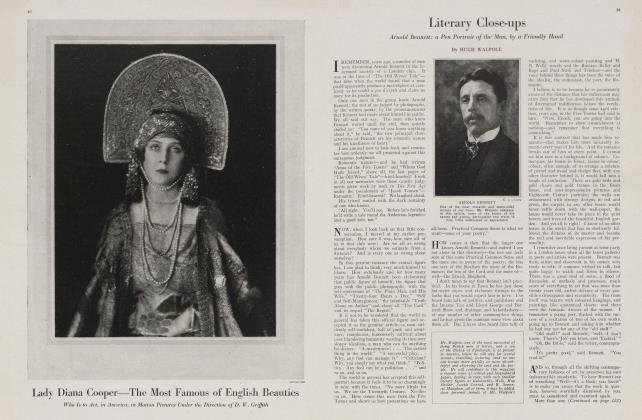

HUGH WALPOLE

SIR HARRY JOHNSTON, and every other student of the Dombey Chronicles, will remember how, on the famous occasion of Mr. Dombey's approaching second marriage, Mrs. Chick explained to poor Miss Tox about Change.

"Change!" exclaimed Mrs. Chick, with severe philosophy, "why, my gracious me, what is there that does not change! Even the silkworm, who I am sure might be supposed not to trouble itself about such subjects, changes into all sorts 6f unexpected things continually! "

No one alive but must have felt on occasion during the last six years that there may be a little too much of this same good thing.

I remember a certain day, in Cornwall, just about six years ago, where, on a green field just above a certain cottage the local village races were held. It was a hot misty Cornish day—the sea below the field was lost in a heat haze, the coastguard cottages were dazzling white against the blue, the farmers and the fishermen mopped their sweating brows in large blue handkerchiefs, the one and only bookie (a stout and almost naked heap of perspiration) was screaming "Two to one on Cornish Cream! Three to one on Lassie!", the little bell (a dinner-bell from the neighbouring public-house) rings, round go the two or three little ragged ponies, the villagers cheer, the sun sinks a little lower towards the misted sea, a farmer mutters hoarsely in my ear— "Looks bad about this 'ere war. They say, in the post-office, that the Germans are crossed into Belgium. Now where might this Belgium be, Mister?"

Six years have passed; Emperors are .worth less than two a penny, butter is worth three shillings a pound, Presidents are somewhere in between the two, names like Verdun and Bolshevism and Foch ,and Hindenburg are household words and there is a statue to Nurse Cavell in Trafalgar Square.

Cornwall Again '

THIS is all platitudinous enough. The point is simply here. Yesterday, once more I climbed to the green field in Cornwall, once more it was a burning, blazing day of heat, once more there was the dinner-bell, once more the bookie shouting "Two to one on Blue Boy", once more the farmers and the fishermen mopped their brows, once more the same air of placid content and cheerful indifferent well-being. "Content! Well-being!" I can hear a villager indignantly remark, "Content? —with butter what it is, and sugar what it is, and new fishing-tackle what it is, and the price of fish the only thing that's going down!"

Yes, certainly, not content as to actual living conditions, but I seem to remember something of the same before the war—complaints about one thing or another always, because that's human nature's way. It is true also that there were certain fishermen and certain farmers absent from that little race-meeting yesterday and they will never return. Nor will their families forget them; their names are inscribed on the granite cross that stands out high above the Atlantic for all men to see and gratefully remember. But there is the reflection there, however eagerly certain poets and pessimists may deny it, that they died gloriously and are heroes forever.

On the whole, nevertheless, the little things remain. When a fisherman empties his boat in the harbour, the gulls flash down in a tangled heap and fight upon the water; the church clock strikes ten when it is two o'clock, as it has always done; the postwoman delivers the letters with the same jokes about the weather, and the same baby (as it seems) pulls the same cat by the ears, two cottages up the road.

Fifty years hence it will be, I do not doubt, as it is to-day. Nothing is more curious than the little difference that inventions and discoveries work upon human nature.

Mr. Wells may have been astonishingly correct in his prophecy of aeroplanes; he has been astonishingly wrong in the effect upon human nature that those aeroplanes are having. Five years ago, what Utopias, what Democracies, what Ideal States seemed to be the only possible outcome of our troubles and disasters!

Now even Mr. Blatchford in his Sunday sermon is compelled to admit that the true Democracies seem to him unlikely because "the people simply don't want to be bothered!"

Nor do I find this depressing. The fine tangled confusion that human nature has always been, human nature will always contrive to be. The war has taught us at any rate this, that Devils are as rare as Angels, and that what we have been we are, and what we are we will be.

The war also has brought many of us to this paradox: that while the love of one's country seems as strong an instinct as ever it was, stronger indeed than it used to be, the loves and hatreds of different countries, the one for the other, are entirely false and unsubstantial.

I believe indeed that impulses, like fevers, can sweep over a country and turn it sick and evil, just as the Prussian fever swept Germany, but about countries as a whole may I be prevented from ever again dogmatizing.

Since my return from America I have been asked to write articles, .books, lectures, on "What America Is", "The Spirit of America" and so on. Before my visit there, buoyed up with text-books, fresh from the latest American farce and the newest American novel, I might have fancied that I could answer my question.

But now may I forever hold my peace.

On looking back through my nine months' experiences in the United States it is, alas, none of the useful things that I remember. I had no real experience of the American treatment of the Irish question; I never learnt "what America as a whole thinks about Prohibition"; I never, God forgive me, even discovered the true and essential difference between a Democrat and a Republican, I am completely confused as to what "the true American thinks about England", I am helpless before the great question of the effect that "the vote will have upon the American woman".

I don't even know what effect it has had so far upon the British woman.

I remember, in fact, all the wrong things about America. I remember, I suppose, the things that I will discover once again if I am alive and strong in fifty years' time and make another American plunge. I noticed the things that I should have noticed in Egypt two thousand years ago, and that somebody will probably be noticing in China two thousand years hence.

Memoirs of America

I REMEMBER, for instance, a snowy day in Boston, with a little soldier large-spectacled, over-trousered, manfully doing policeman's duty in a crowded thoroughfare, new to it, strange to it, pathetic and valiant. I remember the best doctor in the United States taking me to a music hall in Indianapolis and getting extremely excited over two performing seals.

I remember the sun rising over the Arizona Canyon and one of the Show Indians coming out in a blanket from his Show House, watching the glory in perfect silence and then going back to bed again. I remember a great bookseller in Cleveland and a perfect Irishman who was Wellesley College's official chauffeur. I remember a wild-cat in San Francisco's Chinatown, a beautiful lady acting to slow music in a Los Angeles picture village, an orange tree in Santa Barbara, and the purple mist over the Texan desert. I remember General Pershing kissing a little boy in New Orleans, myself catching a red snapper below Miami, and a very clever coloured boxer in Jacksonville. I remember (oh! don't I remember) the librarian ladies at Atlanta, Miss Ellen Glasgow's house in Richmond, and the brown river at Jamestown. I remember Mr. Hergesheimer's smile, and the taxis waiting in Fifth Avenue until the lights change from red to yellow. I remember John Barrymore in Richard III, Richard Bennett in Beyond the Horizon, and Mr. Ziegfeld's justly famed "Frolics"; I remember M. Maeterlinck's one and only lecture, the Harvard-Yale football match, and Mr. Hackett's book shop at Yale. I remember Frank Crowninshield's office, the messenger boys shooting craps in the Senate at Washington, and the Loan Drive in Portland, Oregon. I remember Mr. Ben Hecht's scorn of me in Chicago, and Carl Sandburg's friendliness in the same place, and, in the same place once more, Mr. Scipa acting the second act of "Tosca" so violently that he knocked the furniture over and amazed the conductor; I remember drinking Booth Tarkington's tea, being lost at two o'clock in the morning in a motor car somewhere in Indianapolis, and a lecture of mine before West Virginia University at which nobody at all was present. I remember seeing the top of Mr. Hearst's head at a theatre and not liking the look of it; discussing the Irish question with a lady in Iowa City and only afterwards discovering that she was a Spaniard and hadn't understood a word I had said; and I remember making friends for life with people in Cleveland, Indianapolis, Greencastle and Cincinnati. I remember—well, of course, I can go on forever. There's nothing to be gained by my doing so.

My point, at any rate, is made—and my point is simply this, that it's high time that people gave up doing two things. The first thing is saying "I confidently expect that everything will be better (or worse) to-morrow," and the second thing is saying "In my opinion, the Americans are—" or "if you want to know what I think about the French—" or "Men in my opinion are all—" or "The Democrats of this country deserve—" or "The man's nothing but a Bolshevist", or "Never trust a Russian".

Continued on page 100

Continued, from page 43

The Duty of a Traveller

FIFTY years hence everyone will still be saying these things and with equal injustice. The fact is that human beings move, have always moved, and will always move—on their hearts and their stomachs. Food and a fellow-feeling, those are the things that we want, wherever we may be.

People may say that money is a third necessity but if it be so, only because the gaining of it leads us to the possession of the other two. The duty of a traveller then is three-fold—to see beauty in Nature, to discover food that is comfortable to the belly, and to discover men of like mind to himself.

The country which, for a traveller, provided him most happily with these things, is the country that he will love, and when I say that I love America it will be because of a doctor in Indianapolis, two ladies in Chicago, an oyster stew in San Francisco, a cocktail in Baltimore, and the Arizona Canyon.

Books, of course, have their share in this because they bring between their covers the colour of the country, the friendliness of Man and the scent of good cooking. Who is there who will deny that there is fine drinking behind Mr. Mencken's criticism, the largest of larders displayed in Mr. Hergesheimer's romances, the very mists of the Mexican desert in the pages of Miss Willa Sibert Cather's stories?

It means something, too, that I discovered seventy of Walter Scott's letters in San Francisco, through the courtesy of Mr. Howells, and that Mr. Gabriel Well's courtesy led me to a short story of Charlotte Bronte's and to a manuscript of Anthony Trollope's.

Well, then, are these things America? Assuredly, for me they are. Assuredly, in fifty years' time, there will still be these things for an Englishman in America, for an American in England. What are politicians for then? I have no idea. The papers are filled with their doings. They talk about England and America, make up rules and laws and customs, and sit busily in lofty places. In fifty years' time they will be, I suppose, still about the same business, and in fifty years' time travellers will still be discovering that it is the little things that count and that human beings are the same all the world over and that it takes more than a railway engine to alter the facts of life.

Meanwhile, thank God, one's personal memories remain.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now