Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOur Auction Bridge Refuge

A Sanctuary and Retreat for Persistent—Not to Say Incurable Bridge Addicts

R. F. FOSTER

THE conventional double has become such a popular feature of the bidding at auction that a glance at its antecedents should be interesting, especially as several persons claimed the honor of inventing it.

It is a common but erroneous belief that the no-trump double preceded the suit double, but such is not the case. The original use of the suit double datqs way back to 1912, when the original bid of one spade was the same thing as is now the act of passing without a bid, spades being worth only two a trick at that time.

In an article in the N. Y. Sun, March 2, 1913, three of the bids commonly used by the second hand were given, the dealer having started with one spade. The first was to double, when holding strong spades, but not long enough to bid royal spades, and not enough outside to justify risking a no-trumper. Briefly, the double showed strength in two suits, one of them spades.

Since the adoption of the new count, abolishing the lower value of the spade suit, the meaning of the suit-double has been completely reversed; but its object is the same, to get a bid from the partner. The original double showed strength without length in the suit doubled. Now it shows weakness in the suit doubled, and strength in all three of the others.

The double of a no-trumper, instead of bidding two no-trumps, appears to have been first suggested by Major C. L. Patton, then President of the American Whist League, in the winter of 1913-14. In the N. Y. Sun of May 24, 1914, two hands were given, illustrating the manner in which Major Patton himself used the double, and the benefits derived from it if the partner happened to have any good five-card suit.

In 1915, Bryant McCampbell, whose picture appears in this issue, published the two conventional doubles in his book, "Auction Tactics", under the title of "McCampbell's Doubles", and defines them as follows:

"Doubling one of any suit declares a notrump without that suit. Doubling one notrump declares a good no-trump. All other doubles expect to defeat the contract."

Modern practice has greatly amplified this, and the rule now is that no matter what is doubled, it requires the partner to make a bid if he has made no bid of any kind up to that time. This leaves it open to the player to double bids of two or three, and to double even after two or three bids have been made.

Some recent writers on Auction express strong objections to the double. One says: "Informatory doubles are unethical. They don't mean what they say, and they give information by false or illegitimate bids. They are often likely to be inconvenient to one's partner, and there is always a better way of getting round the same situation."

As this better way has not been explained by the writer quoted, we must accept Bryant McCampbell's opinion that the double has come to stay;not only because it gives the players who use it a decided advantage over those who do not, but because it has added immensely to the interest of the bidding. He insists that no good player who has once used the double will ever give it up, in confirmation of which

he recalls the first important interclub match in which these conventional doubles were ever used.

This was in February, 1915, when he and Herman Steinweber of the Racquet Club in St. Louis, went to New York to play a set match against M. YVaterbury and Douglas Paige of the Racquet and Tennis Club of that city. Talking over various plays on the train, McCampbell induced his partner to try the double as a convention, and they decided to use these doubles in the match, explaining them, of course, very fully to the New York players, who did not think much of them.

After two days' play the New York team found themselves getting so much the worst of it that they decided they would also adopt the McCampbell doubles, and so announced. The much greater closeness of the results of the • play on the succeeding days was undoubtedly due to the advantage of the double being no longer all with one'side.

ONE continually hears about some person or other who is remarkably successful at auction because he plays what is termed a "gambling game". All sorts of absurd stories have been circulated about this game, as if it were some occult way of getting tricks out of the cards that were not visible to the average player. One of these was to the effect that a certain man was anxious to play Mr. Elwell for a dollar a point against eighty cents, but I presume he was careful not to let Mr. Elwell himself hear about it.

There were two players in the South this winter who had the reputation of being experts at this style of game, and were willing to play matches against any who chose to try conclusions with them, and who boasted that if they could only get some of the "book" players into a match, they would win every dollar they had.

I have always been curious to get at the formula for this wonderful winning system, and to learn wherein it differs from the ordinary game of auction, as it has always appeared to me impossible to make a hand worth two or three tricks more simply by bidding them. After having had several opportunities of observing this so-called gambling game, I have found that its success, and therefore its great reputation, is based on three factors.

In the first place it starts by making bad declarations, such as it dare not make against good players. In the second place it makes a specialty of deferred bids, hoping to lead the adversaries to think the hand is weaker than it really is. In the third place, it is of no use except against players of very inferior calibre, who have no knowledge whatever of how to value a hand or of sound bidding.

Against players of equal skill, the gambling game is the biggest loser in the business, because it is continually trying to make more out of the hands than there is in them; but when playing with poor players—with those who are so young at the game that they know absolutely nothing about it—the gambling game is often a big winner. But, any other game would win under the same circumstances.

The fundamental principle of the gambling game is to underbid your hand, with a view to creating a false impression, and getting the opponents to overbid theirs. It is manifestly impossible for such a system to succeed against players who know exactly what their hands are worth, and who never overbid them. Against such adversaries I have found the gambling game stands to be set in about three out of every four hands played. Here is an example of it, a deal played by one of the leading exponents of this style from Chicago.

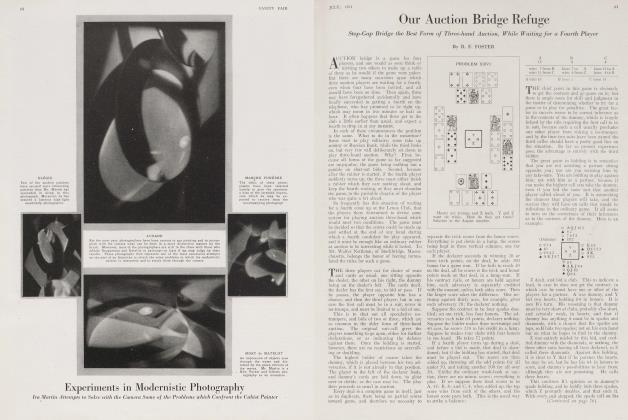

Problem XVI

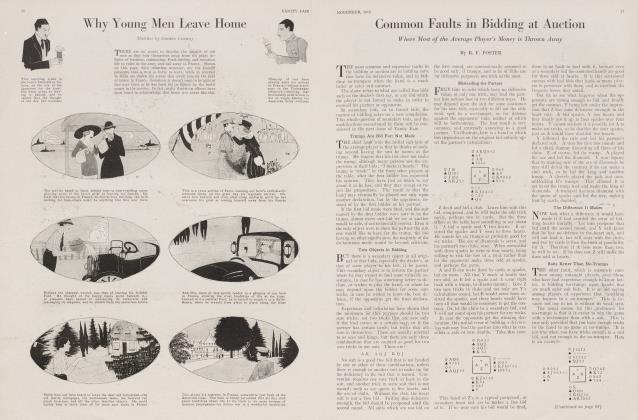

Here is an ending, only seven cards in each hand, that requires very careful analysis in order to meet the many variations in the defence:

There are no trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want five tricks against any defence. How do they get them? The answer will appear in the next issue.

Continued on page 82

Continued from page 71

Z dealt, and instead of bidding notrump at once, as any sensible person would do, he starts in with a gamble on the possibility that someone will be foolish enough to make a bid, and calls a diamond. A bids a heart, Y and B passing. Why Y does not call a spade with six of them is one of the secrets of the gambling system, as between partners. The hands are good for five odd in spades.

Z goes on to two diamonds. Now comes the key to the success of the system-. A knows nothing about bidding, and goes to two hearts, instead of waiting to see what his partner has to say about it. Again Y and B pass, and Z obligingly gambles on a three-diamond bid, which both A and Y pass. It now becomes B's turn to display his ignorance of the value of a hand and go to three hearts, instead of letting Z worry along to make five odd with a minor suit, which he could have done, scoring only 98 points on a hand which is good for 140 if he will bid it right.

Now Z goes three no-trumps, showing a solid diamond suit and a stopper in hearts, with something in the black suits to back it up. In spite of this, B is silly enough to double, and Z redoubles, and A is silly enough to let the redouble stand, when he could go to four hearts and make three, if left to play it.

On the play, the only trick A and B make is the ace of hearts, so that Z scored 720 points. Is this an example of the potency of the gambling game, or an illustration of imbecile bidding?

Here is another example of the tactics upon which this gambling game seems to be chiefly based; the deferred bid. The ultimate success is due to the stupidity of the opponents:

Z's cards were held by Bryant McCampbell, who deals and passes. A bids two no-trumps. What he is afraid of and why he should bid more than one is not clear. When Y and B pass Z says three hearts, and, instead of bidding three no-trumps, A doubles I His partner evidently does not understand the game, or he would answer the double with four clubs, and then Z would have to go to four hearts and be set 300, or let A go back to notrumps.

At three hearts doubled, incredible as it may seem, Z made his contract. A led two rounds of diamonds, Z trumping the second. Knowing A must have king of hearts, he led the jack, and the king went on. A then tried to kill the

spade king by leading ace ten through it. The nine of trumps from dummy forced the ten, Z playing the eight. A led the spade again, and Z trumped with the ace. Now the seven of trumps makes the diamonds.

Apart from the fact that A can go game at no-trump, instead of doubling the hearts, he can easily set the heart contract for 200 if he will start with his longest suit, the spades.

We are indebted to our readers for so many freak hands that it is impossible to publish them all; but here is one that is a gem:

Z dealt and bid no-trump, A and Y passing, B doubling. When Z passed, A called the hearts, and instead of being set for one trick, went game. This is how it happened:

Y led the spade, dummy playing ace. The diamond jack held, and a small one followed, won by the ace. Z led the eight of trumps, covered by the nine and ten, won by the ace. Dummy led a small club, and the finesse of the jack held. Two winning diamonds followed, Y discarding a club on the second, instead of trumping. Dummy discarded spades.

Now dummy trumps the ten of spades and leads a small club, which A wins with the king. Y trumped the return of the club, and Z over-trumped with the king, leading the king and killing his partner's queen. Now A's two little trumps win the game.

Answer to the July Problem

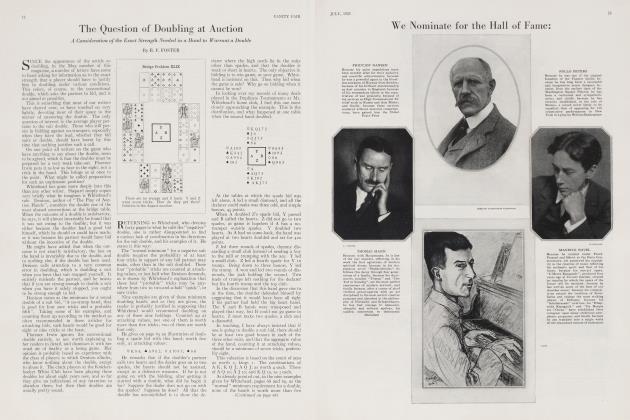

This was the distribution of the card] in Problem XV:

There are no trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want five tricks. This is how they get them:

The trap in the problem is Y's play to the first trick, and those who did not start right must have failed to get the required number of tricks, except against bad play. Z leads the spade ten, upon which Y discards the eight of clubs. (The four will not solve.) Z then leads the five of hearts, which A ducks, allowing Y to win with the ten.

Y now leads the ten of clubs, which B must cover. Z plays a small club, and A discards the six of hearts. B leads a spade, which Z wins with the nine, Y discarding the three of diamonds. Now Z leads the club seven, and the reason for Y's play on the first trick is apparent.

If A discards a heart or a spade, Y will let the seven of clubs hold, and Z makes the winning heart or spade, according to A's discard. If A discards the diamond, Y wins the club trick and makes the four of diamonds.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now