Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOur Auction Bridge Refuge

A Sanctuary and Retreat for Persistent—Not to Say Incurable—Bridge Addicts

R. F. FOSTER

The Philosophy of the Finesse

PRIZES have lately been offered for an analysis of the average player's game of golf, in order to determine which particular shot is responsible for losing most of the strokes in medal play. The idea is to encourage the player to devote special attention to the weakest point in his game. It should be equally interesting and instructive to discover, if possible, the particular bid or play which, for a given player, loses most tricks for him at bridge, with a view not only to point out the defect in the average player's game, but to indicate the remedy.

No matter how closely a player may be able to come to the value of a hand in the bidding, he must be able to get all the tricks the bid shows to be in the hand, or it will be the play and not the bid which fails to get the contract. It is just as costly an error to underplay a hand as it is to overcall it, and the penalty is usually the same. There is no difference between bidding a trick more than the hand is worth and getting a trick less than it is worth, after the hand has been bid to the limit.

It has been pretty definitely settled by both theory and experience that the most common and also the most expensive error in the bidding is overcalling no-trumpers when you have the lead. Milton Work, in his latest book, says the odds against this bid's winning anything are about ten to one.

When it comes to the play of the hand, it might seem difficult to pick out, for special attention, any particular play, among the many variations of the tactics of the game, yet there is one so continually mismanaged by the average player, which results in throwing away so many tricks, that it may easily be placed first among the losing plays of the game. What makes this play more expensive than any other is probably the fact that the situation presents itself in almost every deal of the rubber, sometimes two or three times in a single hand. This position is the ace-queen finesse.

What Is a Finesse?

A FINESSE is any attempt to win a trick with a card which is not the best you hold in that suit, some better cards being out against you. The typical position is ace-queen in one hand, small cards in the other. Probably one of the first things the beginner learns is to lead a small card from the weaker hand, and to finesse the queen. One of the last things the beginner learns is that it is not a finesse to lead the queen to the ace, when you are missing both the jack and king. This is simply throwing the queen away, without giving it a chance. It is like the putt that is never up to the hole.

If we analyze this elementary position, ace and queen in one hand, small cards in the other, we shall find that the reason we finesse the queen is because unless the king is with the second hand there is no way to make a trick with the queen, if you have to lead the suit.

This being so, we get this fundamental principle, which governs every sort of finesse, under any and all conditions:

Every finesse is based upon the hope that the card finessed against is on the right of the card with which we propose to make the finesse.

This applies with equal truth to the acequeen finesse, or the finesse of the jack from ace-king-jack, or the finesse of the ten from king-jack-ten, or even an attempt to win a trick with a guarded king; hoping the ace is on the right. In a smaller way, it applies to the finesse of the jack from king-jack and others. The card finessed against is the queen,, which you hope is to the right of the jack, so that the jack shall win the trick, or drive the ace and make the king good.

The rule applies equally to any distribution of the high cards, and it is through ignorance of this principle the average player throws away so many tricks. Let us suppose that instead of ace and queen being in the same hand, these two high cards are divided: one in dummy, the other with the declarer. Apply our rule, and we hope the king is on the right of the queen; because we hope the card to be finessed against is to the right of the card which we intend to finesse. If it is not there, a trick with the queen is impossible.

This being so, the only way to manage such a situation is to lead a small card from the ace to the queen, instead of leading the queen to the ace. If the queen is led to the ace, the king covers the queen, no matter where it is; but if the small card is led to the queen, and the king is on the right, it must be played, or the queen wins. If it is played, the queen is good for the second round. That is to say, if the king is on the right of the queen, you win two tricks, whether the ace and queen. afe in the same hand, or divided.

Thousands of tricks are lost every day through ignorance of this simple principle, or failure to follow it at the card table. If one will sit and watch any ordinary social rubber, one may see hand after hand in which opportunities for the correct management of this position' are overlooked or neglected. Here is a deal that I saw played not long ago by four ladies who thought they were pretty good players:

Z dealt and bid no-trump, and A led the queen of clubs, Z winning the trick with the ace, to conceal the king. Not knowing anything about the theory of the finesse, she then led the queen of diamonds, and B won the trick, returning the club, which Z won with the king.

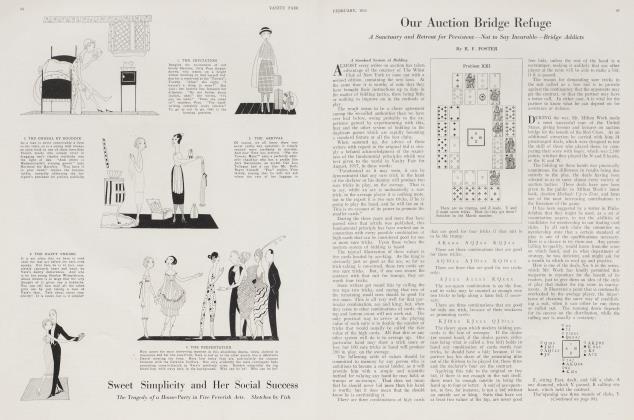

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want five tricks. How do they get them ? Solution next month.

Leading her remaining diamond, Z won the trick with the ace, instead of finessing against the jack. Another diamond was led to force out the jack, hoping it was with B, who had no more clubs. This is hoping with the wrong side in mind.

A won the diamond and made her two clubs, Y discarding a heart and Z a spade, B two spades. The eight of diamonds from A put dummy into the lead again, B and Z discarding hearts. The declarer then proceeded to make the same mistake in hearts that she had already made in diamonds; leading the queen to the ace. A winning the trick with the king.

A returned the small heart, and the ten forced the ace. Now the declarer makes the third mistake, leading ace and small in spades, and finessing the jack, instead of leading the losing heart and making A lead spades; but of course there was no way of telling who had the best heart. B won the second spade lead with the queen, and made the heart, setting the contract for one trick.

This line of play was supposed to make three finesses, and all of them lost. 4iVery unlucky, partner," was the only comment. "All the kings, and queen of spades, on the wrong side," whereas the truth was that they were all on the right side; but the declarer did not know how to manage finessing positions. With this knowledge, properly applied, it is a game hand for the heart declaration, instead of being set one.

On winning the first trick, it should have been evident to the declarer that in order to win a trick with either or both the red queens, the king of those suits must lie to the right of the queen. Z's play, therefore, was to lead a small heart. A must put on the singly guarded king at once, for fear of losing it. Another club establishes the suit.

Now Z puts dummy in with the queen of hearts, so as to lead a small diamond from that hand," hoping the king is to the right of the queen. If the king of that suit lies to the left of the queen, game is impossible unless the hearts drop. Having no clubs to lead, B passes up the trick, and the queen wins.

(Continued on page 86)

(Continued, from page 65)

The declarer returns the diamond, knowing B must have the king guarded, and finesses the nine against the jack. B would naturally lead one of her 'two equals in hearts, Z winning with the ace, and A discarding a spade, as the diamond would make both dummy's good.

It is now a simple matter to lead the losing heart, so that B shall have to lead spades or diamonds up to dummy, Y discarding the losing club. A wins the last trick with the ten of clubs, or B wins it with the queen of spades, depending on which hand has the lead for the last trick, Y or Z. Even the jack of diamonds might win, if B leads the spade, which is not good play.

It is quite true that all the kings finessed against in this hand win tricks, and that the jack of spades cannot win, as the queen is on the wrong side, unless spades are led; but the point is that although the adverse kings win, the declarer's queens are not thrown away.

The Mystery Solved

IT was a duplicate game, for ladies only, ten tables playing two deals before changing adversaries. In looking over the scores, to discover, if possible, how they had fallen so far behind the winners, who were supposed to be very poor players, two of the ladies who thought they should have been top, found a deal in which one pair, sitting E and W, went game in hearts, while every other pair setting E and W had lost heavily on that board at any declaration.

On asking the pair that played the N and S hands at that table for an explanation of what happened to them, the cards were laid out, this being the distribution:

It appears that the play went this way. S dealt and passed. W bid a spade, N passing and E denying the spades with two hearts. A small club was led, and dummy went right up with the ace, leading a trump, finessing the jack and catching all the trumps in the N and S hands.

The eight of spades brought the ace from S, who led another club, won by N with the king. N then laid down the ace of diamond, following it up with the queen, whereupon E played the king, announcing that she had the thirteenth trump, which she exhibited, and that all dummy's spades were good.

Admitted and scored, four odd and game, with simple honors. What is the matter with it?

"But how did she get dummy in to make the spades?" demanded one of the aggrieved investigators.

"Really, I don't remember. We did not play the hand out, as we knew the spades were all good and she had the last trump."

Answer to the April Problem.

THIS was the distribution in Problem XXIII, in which the defence is forced to some peculiar discards:

There are no trumps and Z leads: Y and Z want five tricks. This is how they get them:

Z leads the eight of diamonds, upon which A puts the ace, B discarding a heart, as the six in A's hand still guards that suit. If A returns the diamond, B discards the king of hearts, to protect the clubs. Z can discard from either of the black suits ter meet this defence; but if B discards a club, on the return of the diamond, Z must let go a spade. If B discards the spade eight, Z discards the club three.

If A leads the deuce of hearts for the second trick, Y puts on the ace and leads the spade. Z wins the trick, and throws B into the lead with the losing spade, so that B must lead, and loses all the clubs, as Y and Z each have three left, Y discarding the heart on the second spade.

If A leads a high club for the second trick, Y passes it, and Z wins it, leading a heart to Y's ace. Now the second spade lead puts B in, as before.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now