Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Future of Mah Jong

Reasons for Past Changes in the Game and for Possible Changes to Come

R. F. FOSTER

WE have had two years' experience with this famous Chinese game, and its popularity has passed the crest. Although probably more people are playing it today than a year ago, they arc not the same class, from being about the one and only game played and talked about in society and in the newspapers, it has now settled down into its proper place as just "another game" which has been added to our list of domestic amusements.

During the past two years, Mah Jong has depended for its vogue largely upon the fact that it was a fashionable fad, to be played with expensive imported tiles, and to be played in a different way in almost every large city, there being no standard rules for the game, as no complete set of laws had been issued, even in China, the country of its origin, until a tentative code was published in this magazine just a year ago this month.

Today, and from now on, Mah Jong will have to depend on its merits as a good game, apart from any artificial support as a fad. This causes us to inquire what makes a good game, and what must be done to insure the permanent inclusion of Mah Jong in that category. The secret of the perennial popularity of certain games among certain classes of society depends on the game's being adjusted to the intellectual grade of the players, and according to whether they demand intellectual recreation, or simply a means of passing the time. One cannot get society to adopt five hundred or cinch as the thing always to be expected after a luncheon or dinner; neither can one expect those who work chiefly with their hands all day to be anxious to clear off the dishes and get ready for a game of Boston or ecarte.

While Americans have made great strides in the matter of the paraphernalia with which Mah Jong is played, giving us better tiles, of more uniform size and patterns, greater durability and cleanliness, with more substantial boxes to hold them, and have also added many new features, such as special tables, racks, and counters, the benefits conferred have been more than counterbalanced by the injury they have done to the game itself.

AS originally played in China, Mah Jong was a game requiring the peculiar oriental type of mind to play it in its perfection. One of the chief points was the close attention to inferences as to the objects of the opponents, and the frequent sacrifices of one's own game for the sake of preventing an opponent from going out with a big hand. This highly important feature of the game was not even touched upon by any one of the hundreds of teachers and writers who introduced the game to American players. Even Babcock, whose text book was the most widely read of any, never mentions it.

The American idea of the game was entirely selfish. It was always to get a big hand yourself, no matter what others were trying to do. Flayers rebelled at the mere suggestion of penalties for putting another player out with a big hand. The skilful manoeuvring to go Mah Jong with a small count, winning a trifle from each player and paying nobody, came to be looked upon with contempt, not only because this "dogging" the hand was a picayune game, but because it interfered with the plans of those who were trying to build up a big hand by refusing to go Mah Jong with a small one. If the game was capable of yielding scores running into the thousands, why not play for them:

* Copyright, 1924, by R. F. Foster

The first step in this direction was to head off the players who persisted in dogging their hands, by forcing them to wait for big scores, thus delaying the game long enough to give all an equal chance, at the same time avoiding the constant pulling down and rebuilding of the walls.

THIS led to the first and the most important II and far reaching change in the original game, which was the rule that no player could show a hand of Mah Jong if it contained tiles of more than one suit. This carried with it the certainty of at least one double, and the possibility of any number from that to seven or eight, and at once raised the average value of the winning hand from about 80 to 300, but at the expense of a large percentage of drawn games, which more than offset the rebuilding of the walls in the original game.

Some months later the qualification of a double for a cleared suit was extended to take in any double. The usual doubles being Dragons or Winds, and the unusual ones being all counts or all Terminals, and as the odds against getting any of these in the original hand were 7 to 1, the play in this form of the game reverted to trying for the cleared suit, whether there was any natural double in the hand or not.

The consequence of these changes was that, although American players did not realize it, the game degenerated into a succession of drawing tiles from the wall, and three times out of four discarding them again, without any further intellectual effort than to glance at them to see if they were of a certain suit or not. The only interest was the mild excitement of expectancy, no attention being paid to what others probably wanted. If one drew what one did not want, it was discarded at once, no matter how valuable it might be to an adversary.

There was no change in the plans, once the suit to be played for had been selected. This monotony, this total absence of variety in the objective, destroyed all the intellectual interest in the game, without which it could never hope to compete with such a game as bridge, which calls for the constant exercise of the faculties of attention, observation, inference, and judgment, and furnishes endless variety in the problems it presents and in their solution.

IN my opinion these changes in the rules, which have led to the obsession of playing always to clear a suit before anything else, have done more to lessen the interest in Mah Jong than any disputes about the rules. If the game were as interesting as bridge, in which the players arc continually disputing and arguing about differences in bidding and play, they would continue to play Mah Jong in spite of these differences, just as bridge plavcrs do. Who ever heard of four bridge players suggesting to play euchre, because they could not agree on taking out with strength or weakness?

People will not continue long to play a game in which they do not find the intellectual stimulus and variety which alone can make it a mental recreation, and not merely a pastime. Mah Jong, in the hands of American players, has degenerated into a pastime, with the natural result that it is passing into the hands of those who play games for amusement, and care nothing about the intellectual features.

We have ourselves to blame for this. The American players, in their anxiety to get big hands, went about it in the wrong way, by trying to make them out of insufficient material. They tried to force small initial counts into producing large final results by insisting on waiting for special doubles to accumulate, instead of correcting the inherent defect in the original game, which is, that half the sets laid down during the play have no value whatever, so that half the time the players are striving and waiting for doubles that double nothing. The scoring elements in the original game were quite sufficient for that style of play, but they are not sufficient for the style of game Americans want to play today. There is too much space wasted on sets that produce nothing at all.

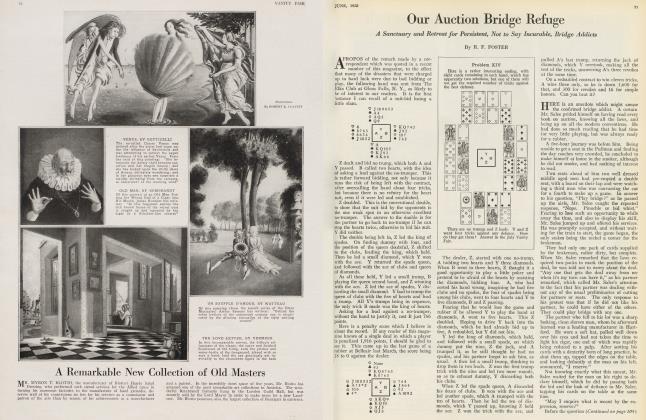

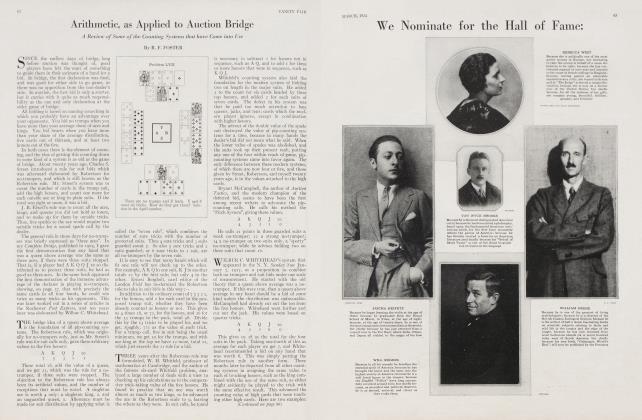

TABLE OF POSSIBLE SCORES Being Changes and Additions to Those Now in General Use.

Triplcts and Kongs

Grounded In Hand

3 of Own&Prevailing Wind 8 16

3 of same colour Flowers . 12 24

4 of Own & Prevailing Wind 32 64

4 of same colour F'lowers . 48 96

Sequences

An open sequence is all

Simples.

A closed sequence ends with 1 or 9.

Open sequence of 3 Simples

in suit.2 8

Closed sequence of 3 in suit 4

Open sequence of 6 in suit . 4

Closed sequence of 6 in suit 8

Sequence of 9 tiles, all one

suit.12

Pttirs

Pair of Simples, same suit

Pair of Terminals, Winds, or

Dragons.

Pair of Flowers, same colour .

Individual Flower .

One Double, for All Hands 4 sets, triplets and/or kongs, and an odd tile.

4 sets, all sequences, and an odd tile.

To go Mah Jong, the player must have least twenty points, exclusive of any doubles or bonuses.

Continued on page 100

Continued front page 78

The future of Mah Jong seems to depend on the recognition of three things, which will probably be admitted by any candid observer.

First, and most important, is the practical impossibility of getting American players to go back to any game which they have once abandoned. The history of all games teaches us that. No amount of argument will induce the great mass of players in this country to return to the original Chinese game, with its dogged hands and small counts. It may be very deep, and very interesting from the oriental point of view, but it is not attractive to the mass of American players.

Secondly, it must be evident that if Mah Jong is to retain or to regain its position as a mental recreation, in any way approaching bridge, it must be relieved of the monotony of playing almost exclusively for cleared suits and one doubles. Something must be done to provide it with the sustained intellectual interest that should attend every tile drawn, and every discard made; giving the player something to plan for, to manage, to change, to improve, from the first tile drawn to the last discard.

Thirdly, there must be ample opportunity for getting the big hands that are such an attraction to the average player, and that one is never tired of talking about. These must be made possible without surrounding the player with a number of restrictions that hamper his game and force him into a groove that discloses his objective to his adversaries, too often resulting in drawn games.

In looking at what must be in some form the future of the game, the important point is the score. The fundamental counts of the present game are riduculously small as compared to their possibilities in combination; but the combinations which result in high scores are extremely rare, on account of their mathematical improbability. The odds against a hand worth ten thousand are about 10,000 to 1.

The first change that will probably come about in the scoring will be to utilize the material at hand by increasing the scoring possibilities which are probable, instead of depending on those that are improbable.

There is ample room for this, as suggested in the article in the August number of this magazine. At the top of every score card we find the notice, "Sequences have no value". Why should they not have a value? They are planned for just as much as triplets, and some of the most interesting plays in the game hinge upon the flexibility of sequences in forming sets. Why should not a sequence of Simples not be worth as much as a triplet of the same kind? Why should not a sequence ending with a Terminal not be worth as much as a triplet of Terminals?

The proportionate values of some of the sets are at present out of all keeping with their probability, and some are illogically rated. Why do we double the value of a player's Wind if it is also the Prevailing Wind when he has a pair, and do not double it when it is a triplet? Why do we give a double for three Dragons, and not for three Flowers, although we give three doubles for four Flowers? To be in proportion, the bouquet should be worth thirty doubles.

When it comes to the pairs, why do we give a count for only two, sometimes only one, of the four Winds, and for any Dragons, but nothing for a pair of Terminals, Simples, or Flowers?

We give a double for all one suit, or all Terminals, to the non-winning hands. Why not also a double for four sets of triplets and an odd tile; or four sequences and an odd tile?

By adopting James S. Cobb's suggestion, and throwing the eight Flowers into the playing set, we get a much more harmonious game, and this will undoubtedly lxone of the future changes, even if they are left at their present individual value of four each, and a double for one of your own number. By making players get at least a pair of the same colour before they can go Mah Jong, and allowing them to discard or pung the Flowers, we at once do away with the lucky element that so many object to; even to the extent of refusing to play with the Flowers in the set.

The largest odds in the game are against a bouquet of Flowers, and they must consequently be given the highest score. All other scores should be proportioned to the probability of getting them, and the usual rules of twice the value in hand as compared to grounded should always be followed.

If these changes are adopted, they will be found to be merely additions to the usual score card, and these additions are given in the table at the head of this article. The writer will be glad to send complete score cards to any who ask for them.

The one condition that supplies the sustained interest and demands the exercise of observation, inference and judgment which the one-double and cleared suit games lack, is W. F. Smith's rule that the Mah Jong hand must be able to show at least 20 points, exclusive of any doubles or bonuses. Join this to the extra scoring possibilities indicated, and there will be no lack of interest, no disclosure of your objective to your opponent, and no drawn games.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now