Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe First Performance of "Hamlet"

As It Might Have Been Reviewed by Several of Our Living Dramatic Critics

SAMUEL HOFFENSTEIN

I. Mr. Heywood Broun

AFTFR seeing the first performance of Master William Shakespeare's Hamlet at the Globe Theatre last night, we are not sure whether we like it or not. We had four hours of uninterrupted drama in which to make up our minds, but many a woman has taken more time than that to decide less important matters, and we arc brave enough to deserve one of the prerogatives of the fair sex. We don't know yet whether we are thoroughly in sympathy with a character in a play who thinks twice before acting. We go to the theatre to sec him act.

We don't mean to say that once the author got things started he didn't step lively. On the contrary, we haven't seen a stage so beautifully incarnadined in a long time. There was action enough to make the Spanish Main look like Main Street in Canterbury. But by the time the play got going, we were going ourselves. We were tripping towards the exit about the same time Hamlet was being tripped up towards a stranger exit than the one we took. There were stretches in the play when it seemed to us there was something rotten in more than the state of Denmark.

For the benefit of those who are interested in the new drama, and especially in the works of Master Shakespeare, we won't give the plot, and incidentally, the author, away. Let them go and get the hang of it themselves. Personally we prefer the simplicity of the morality and miracle plays, or the streets of London. We have found more drama on London Bridge in an hour than the licensed mummers of the Globe Theatre give one in a fortnight. But we realize we are with the unintelligible minority.

HAMLET is the Prince of Denmark, whose father has died under what looks like mysterious circumstances. The mystery is deepened by the fact that immediately after his father's death, his mother marries his father's brother, who succeeds to the throne. Hamlet doesn't like his uncle, who seems, by all accounts, to have been a kind of poor relation compared to his father, and not only a schlemiel, but a sinister schlemiel at that. He resents also what he terms his mother's incestuous marriage, although it looks like a pretty poor incest to us. But even queens ought to keep up some show of regret lor their husbands' disappearances. Hamlet suspects them both of having a black hand in it.

The suspicion turns out to be correct. The culprits actually haven't a ghost of a chance. The spectre of the late king appears to Hamlet and gives, the shame away in one of the best scenes of the play. This scene had suspense, action, and the kind of mystery we like in a melodrama. We could actually feel the shivers playing leap-frog in our spinal column. We were glad we had an aisle scat, since we are unfamiliar with the ways of the spirit, and thought that, in an emergency, it were just as well to have a clear ghost behind us.

Anyhow, according to the testimony from the other side, it seems that Hamlet's uncle and mother killed his father by giving him an earful of poison, on the theory that he wouldn't believe everything he heard. It wasn't the kind of trick you could play on a sleeping man without his resenting it when he woke up. Well, that's the state the ghost was in. He was as het up about human vengeance as a man could be who was thin to the vanishing point. He was, in fact, the only character in the whole play we could see through. It was easy enough to infect Hamlet with his spirit, and the latter promised to avenge the murder, no matter what the odds were against his getting even.

From there on, we confess the play is unintelligible to us. It doesn't seem true to life. We can't follow the workings of Hamlet's mind, and his explanations are like acrostics that don't bring home the Bacon. Perhaps Master Shakespeare had something subtle and profound up his sleeve; but if so, he didn't succeed in rolling his sleeve up for us. It may be we are out of tunc with revenge. We are an amiable fellow ourself, and as willing as the next to let doggones be bygones. What's an earful of venom among members of the same family?

It seems to us that Hamlet should have gone right out and made a killing. He had the facts from the corpus delicti himself; he was determined to square accounts, and yet he does nothing but play mad and produce a show. Why he should play the sleuth when the evidence is all in, is beyond our comprehension. Perhaps the soliloquies were intended to give him a chance to sharpen his sword.

The fact of the matter is that Hamlet is less truth than poetry. We don't share the popular superstition about poetry. It strikes us as a dodge. You will notice that there is no such thing as blank prose, although a lot of blank people use it. Master Shakespeare's blank verse is workmanlike and pleasing, but it retards the action and distorts the characters. It is too great a temptation to the author, his people and the actors. Feed them prose and they'll jump through a hoop.

Master Burbage's performance was pitched in too low a key. We like more noise in our melodrama, and we don't even object to a little ranting. This absence of sound and fury marred the performance of the other players also. You can carry breeding too far, especially when it's the breeding before bloodshed.

To our way of thinking the two young Hebrews who plavcd Rosencranz and Gildenstern gave the best performance of the evening.

II. Mr. Percy Hammond

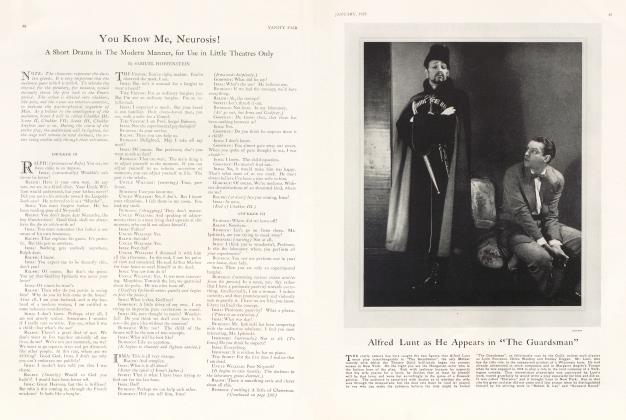

MR. WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE'S Hamlet, presented with ducal eclat at the Globe Theatre last evening, teems with royal incest, princely cogitations and the vengeances and alarums of the high and scholarly. It is a pleasure to report that the noble and glittering auditors received the composition of the inspired poacher-playwright from the Stratford meadows with sincere, if decorous, tumult, and that Mr. Richard Burbage performed the title-role with distinction and symmetrica Is.

The poet's alternately swift and stately procession of scenes reveals a state of putrescence in the kindred monarchy of Denmark. There is something rotten somewhere, and the symptoms and stigmata point to infection at the throne. There is murder abroad and afoot, and the very ozone is charged with the minatory and illicit. Fhe guards on the ramparts tremble from heel to shako with unsoldierly premonitions, and the tall and intrepid hussars are obsessed with a sense of the dire and the doleful. Investigations are in the air and abeyance; the loyal populace looks with silent but sour suspicion on its liege lords and their supernumeraries; yet the mystery remains caviare to all but the generals. It is obscene but not heard. Meantime, our pallid and pensive prince, forsaking the sedative honies of the boudoir and ball-room, vents himself in nocturnal excursions, meditations and forebodings. The stoppers are about to be removed and the vials of vengeance will pour forth their exacerbating bitters.

BEHOLD the heir-apparent pacing the starry bastions in expectation of a tip-off from the Beyond. There have been eerie whispers in the gloaming, and the tenebrous later hours have hinted of spectral grudges and complaints. "There is sedition in the graves," says his buddy, Horatio, "and the mortuaries have turned State's evidence. A ghost wants to sec you, Hamlet, so stop, look, and listen, and you will sec what you will see. All clues point to the yawning crypts, and the hunches indicate that the dead are about to squeal."

No sooner said than the waiting spirit enters upon his cue, gliding hither and yon, with the lightness of the disembodied and the decently disinterred. "It's the governor, by Holy Writ and that stride," says Hamlet, trembling with princely and filial excitement, "though I have never seen him before save in the royal habiliments and dignity. But the lineaments are unmistakable, and no man would so become a sheet. He beckons me, bearing in his insubstantial bosom the low-down on this felonious business." "By all means," counsels the practical Horatio, "ask dad; he knows."

There follows in a sequestered ingle, a confession of kingly horrors and malpractices. They have done him dirt, it seems, in more ways than one, and the very earth-worms clamor for vendetta, nipping him in the blood. His brother, the regnant monarch, with the abetment of his lewd and unseemly consort, Hamlet's mother, has poured insidious venom into the aural porches, while the owner slept, thereby liquidating the latter's further claims to mortal tenure and the Danish crown. Life in Copenhagen was sweet; the court teemed with frolics and the fair, and it was a measly thing to expect, even from one's relations. The ethereal victim was, therefore, full of damp rages and earthy, though just, malice, and insisted with grave heat, so to speak, on retribution and mayhem. "Owing to circumstances, Hamlet," he says, "I've got to pass the buck to you, but I want you to give these crooks the hook, by hook or crook. Avoid the polizei and the bailable revenges, and charge it up to personal injuries and affronts. If I get even, I'll sleep."

Continued on page 98

Continued from page 65

Thereafter, the drama moves through the major poesies to gratifying assassinations and a debacle both ineluctable and multitudinous. Everybody gets his or hers, with a generous residue for the innocent and the bystander. We shall not betray the details of the procedure out of an honest regard for the unities of justice. In confidence, however, we wish to remark that our hero is a man of the loftier cerebrations rather than of the punch direct, and the tragic consummation is retarded with many noble passages on the pros and cons of conduct. In the course of his stratagems and procrastinations, he feigns the various nuances of madness, thereby leading the trusting and tender damsel of his heart to untimely heartbreak and demise. The studious and attentive Londoner will find, in a visit to the Globe Theatre, both profit and prosody, and a competent reading and enactment by Mr. Burbage and his associates, save in the instance of the gentleman who played Ophelia, who was too stalwart for the optical requirements of fragile virginity. We recommend a lean and deciduous vegetarian for the future performances.

III. Mr. George Jean Nathan

Dr. William Shakespeare's Hamlet is two-thirds walla-walla and onethird tolerable melodrama of the species now equally popular with the hod-carriers and the gentry. The former like it because it gives them an eyeful of sword-play and a chance at vicarious gizzard-slitting; and the intelligentsia are at the moment breathing heavily under the delusion that the fat fustian dispensed to them by the contemporary boob-ticklers is poetry of a high order. The plot is the usual shakedown from the Holinshed folio, and has been rife in sundry sagas since the days of Nebuchadnezzar. It is Danish pastry served to mustachioed brigands in the baronial hall, to the clanking of chains and the clinking of tankards, w'ith the portcullis raised and the halberdiers at attention on the ramparts. At an early hour this morning, long after this critic had withdrawn to his observatory and the occult sciences, the mingled salvos of the yokels and the carriage-folk penetrated his seclusion and caused him to spill half a seidel of Pilsener onto his newly burnished buskins.

This Signor Shakespeare is a rural maestro with no mean talent for rhetoric and alarums. In the current instance, he has devised a solemn and warlike opus with some pretty passages, and two or three scenes of passable excitement. As for the rest, so piffle-headed an anachronism as Max Marcin could have done it better, while so abstruse a cogitator as Samuel Shipman would have had to extend all his vast faculties to do it worse. The bushwa extant, to the effect that the Rev. Dr. Shakespeare is an inspired creator of character, derives, no doubt, from the fact that his principal personages have excellent connections at Court and do not eat sole marguery with a spade, while his peasantry is even more ridiculous than the Lord intended them. Upon actual examination, his characters turn out to be as real as Prester John Davy Jones's locker, or the Spanish peril.

Prof. Richard Burbage did his duty in the title-role with decent regard to the comfort of the customers, but the others in the cast perpetrated the usual cabotin assaults on the English language and the human tympani. The fellow who played Ophelia, in particular, a colossal oaf, with bellows like a Cyclops, acted as if he had been fed raw meat for a week before being permitted to impersonate this most unfortunate piece of baggage.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now