Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

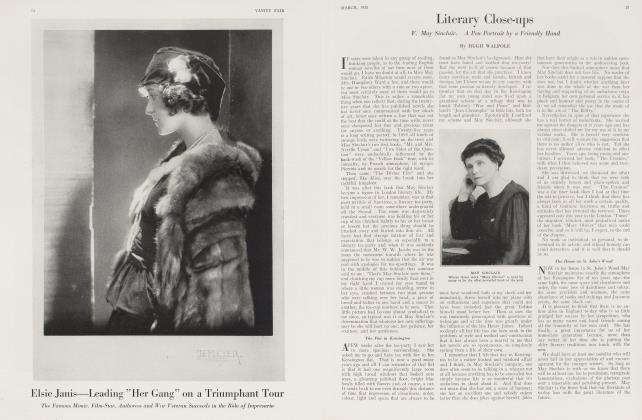

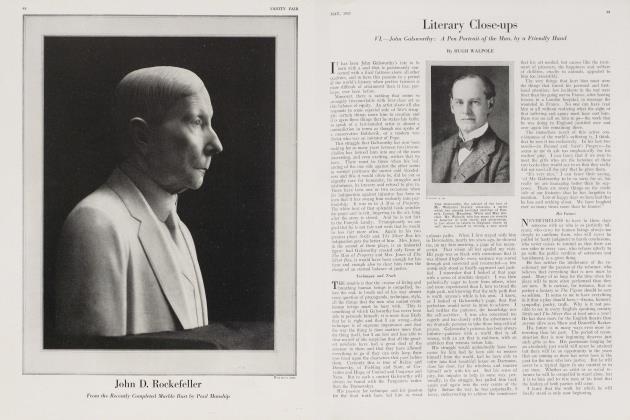

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLiterary Close-ups

IV.—H. G. Wells: A Pen Portrait of the Man, by a Friendly Hand

HUGH WALPOLE

IT must be a great many years now since H. G. Wells decided that he would take no steps to confine the natural exuberance if his genius.

In the early days he must have known all hose struggles that come to every writer of talent, between the spirit of possession and the spirit of the artistic conscience. One can see, in "The Time Machine", "The Wonderful Visit", "The War of the Worlds", something of this struggle; and for quite a long time Wells' artistic conscience won.

But, in the end, or, rather, very nearly in the beginning, his interest in the world was too strong for him: he was making his discoveries too swiftly, and, for our gain perhaps, rather than for our loss, he threw aside his privacy, cast away his reticence and, as Hilaire Belloc put it, decided "to grow aloud in public."

His books have been, ever since "The First Men in the Moon", a series of self-confessions and self-confessions entirely unreserved and unashamed. "Life is too interesting," he said long ago, "for us not to admit the whole of it. What I want to do is to startle all you sluggards and muddlers and idlers into some kind of apprehension of it. Then we'll get something done."

There is no doubt that more than any man alive in the world to-day he has startled his Fellow men into an apprehension of life, and that is so great an achievement that there is no need to argue the rest—as to whether he is a great artist, or a real novelist, or a profound philosopher. He has not allowed himself time I think to be, on many occasions, these things, although "The Wonderful Visit" is surely great art and "Tono Bungay" is a great novel. But his hurry has been phenomenal; it is as though he were haunted forever by a vision of the world slipping between his fingers and threatening to leave him, suspended, in an icy void. This apprehension is not selfish, however: more than any man alive he longs for human progress, aches for the day when men and women will make something nobler and happier out of the conditions that they have been given; and prays with an urgency that is poignant for a millennium that history must surely have told him is ever illusory.

I don't know that in this vision he cares very greatly for the individual. The individual exists rather as food for Wells's education than for a personal life and happiness.

The Shop-Keeper Motif

HE is impatient, angry, happy, scornful, merry, despondent, replying always to the mood that the world at that moment may be in, and too deeply absorbed in his own sense of personal existence to delve far into the personalities of those near to him. For that reason he is not, I think, a great psychologist. You will find always in his novels the same two figures recurring, the little self-educated shop-keeper who sees further than his fellows, and the wise, noble modern girl who understands his problems.

Even the able young politician, in such books as "The New Machiavelli" is only a later development of the same little shopkeeper, rejecting with confident scorn the classics and

culture that he has never known and regarding the society over whose barriers he has climbed with an instinctive awe of which he is sublimely unaware.

Wells is not a creator of men and women, but he is a superb poet. There are passages in every book that he has ever written that force the reader to feel that he is face to face with the beauty and force, pathos and energy of life as he has never been face to face with them before, and it is for these passages, I believe, and not for the rather amateur philosophy, the rather childish anger, and the sometimes petty disappointment, that he will live in English literature. That he will live, and live gloriously, I am quite convinced.

It is now eight years at least since I had any real view of him. I had, somewhere about 1910, come up to London to try my fortunes as a writer and, by a piece of good-luck for which I can never be sufficiently grateful, one of the first friends I made was Mrs. H. G. Wells. She and her husband were then living in a house on the Hampstead Heights and soon after our first meeting I was invited to join in the Wells's Sunday parties. That was a wonderful chance for an ignorant, country-fed, self-confident young man. A certain number, perhaps half a dozen in all, were invited to breakfast. A great breakfast was prepared and then, as soon as everybody had sufficiently appreciated it, the walk began. We started off at about ten in the morning and were out generally all day. I remember very dimly anyone else who was there, .but the simple fact was that Wells completely engulfed the rest of the party in his dominating presence.

He talked incessantly, hurling into the air everything that came to him, telling stories, discussing novel-writing, the drama, giving little pictures of people whom he had known— Gissing, Crane, Henry James, Harland,— laughing, sometimes almost dancing, stopping once, I remember, when we came to a piece of common to play an amateur game of cricket with a coat and an umbrella. Above all he was utterly unsuperior, listening patiently to the ignorant opinions of a country bumbkin and taking quite seriously the ideas about art of someone who had not come anywhere near the position of an artist.

To me those days meant everything and I shall be grateful for them until I die. It was not only the beauty and colour of the Hampstead rooms, the quiet friendliness of Mrs. Wells, the sense that everyone around me was young and happy; it was, far more than those things, the contact with a mind so lively, so vibrant and adventurous that one walked the country roads with a sure knowledge that life was a marvellous thing and, however severe its lessons might be, its interest would always surpass and overcome its penalties.

I think I realized even in those days that he was not a good critic of literature. He was too susceptible to prejudices and too swift in his judgments. He would admit his prejudices, however, and he had a fine healthy scorn for sham reputations and vainglorious ambitions. He had then—he has still—a preference for the new, the undiscovered, the unjustly neglected. He could praise with a magnificent generosity, and many a man has to thank him for the exercise of that great quality. The help that quite recently, for instance, he gave to, that beautiful book of Frank Swinnerton's, "Nocturne", will be in everyone's mind and such writers as W. H. Hudson, Mary Austin, James Joyce and Dorothy Richardson all owe him great debts for his incessant championship.

Wells and the War

HIS reactions to the war have been as many and varied as the phases of the conflict. More than any other writer he has represented, nakedly, the mind of the thinking man who, stationed a little behind the actual conflict, has passed from confidence to disappointment, from disappointment to agony, from agony to a new hope. It is not fair to say of him, as many have said, that the propagandist in him has swallowed the artist. He has never been a propagandist, but rather a poet chanting, as did the minstrels of the dark ages, the adventures, catastrophes, victories of the campaigns. The History of the World upon which he is now engaged will possibly disappoint the pedants and professors—it may prove to be one of the finest Sagas in the English tongue.

When he leaves us, and when some of the antipathies that he has aroused have died away, there will be a void that no other man can fill. It is difficult to prophesy, but it is hard to believe that there will ever be a time when men will not want to know the colour and form and texture of these strange days in which we now live—and no other writer will be able so completely to satisfy that curiosity as H. G. Wells.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now