Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowRealism and the New English Novel

A Practitioner of the Established School Discusses the Messiahs of the New Faith

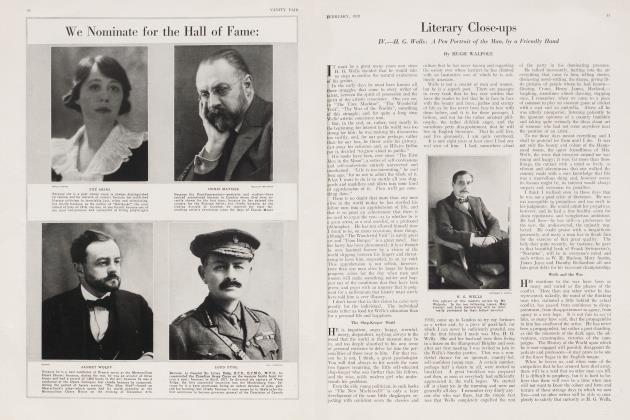

HUGH WALPOLE

I AM most anxious not to take this heavy subject too seriously, but it isn't my fault if the critical pundits of England and America, Messrs. Middleton Murry, Ford Maddox Hueffer, Arnold Bennett, Valery Larbaud, Ezra Pound, Gilbert Seldes, and even Vanity Fair's own Mr. Edmund Wilson, Jr.— it is not my fault if these gentlemen have been so thunder-struck by the superb genius of Mr. James Joyce and his Ulysses that they have completely lost their sense of humor and proportion.

I am not concerned here at all with the question of Mr. Joyce's genius. He has an exceeding fine talent. He can string words together as no one alive writing today can do. He can see more in a spot of soup on an Irish alderman's waistcoat than can any microscope yet discovered by man. His audacities, his freedoms, his perpetual putting of his long, thin fingers to his superior nose,—to these things there is no end.

The Break-Up of the Novel

THERE is, for that matter, no end to Ulysses, and however loudly the conquerors may scream and cry, I refuse to believe that there is anyone yet who has read Ulysses without being at times intensely bored and discovering at other times how terribly many passages have mis-fired and failed to hit their mark. These things, however, are arguable. Anyone who could write the last fifty pages of Ulysses is a great man and we ought to throw our hats into the air with pleasure at his splendid talent.

That is not the question. The question here is whether, as Mr. Middleton Murry has just declared in the last number of The Yale Review, the appearance of Mr. Joyce, M. Proust, and certain other lesser stars in the literary night-sky—whether these things mean the break-up of what is known as the novel, so that no longer will simple people be able to sit by the fireside, their toes on the fender, and hear with their favorite pirate the thunder of the surf upon the far-stretching shores of the Spanish main or drink a cup of tea with their favored heroine as she sits in her little cottage wondering sadly why her husband has not come home.

These simple joys and pleasures are to leave us once and for all; they are to leave us apparently because the novel has stretched forth into regions so erudite and so dusty that story-telling can no longer breathe in that air. The only purpose of the novel in the future, apparently, is to give us the subconscious reactions of certain complexes that have been doing what they shouldn't or are afraid that they very shortly will.

Now there was a time and not so very long ago either, it was—in fact, no later than last week—that I read of the adventures of certain gentlemen called Porthos, Aramis and Athos, with extraordinary pleasure and interest. These gentlemen had no complexes at all. It may have been that Aramis had one or two hidden away somewhere. There was the Jesuit complex perhaps, and a modern Freudian would certainly have said that he was undersexed, but Porthos and Aramis would indeed be bewildered in the company of Miss Richardson's Miriam, Mr. Joyce's Mr. Bloom, the inhabitants of Miss Evelyn Scott's "Narrow House", the elegant felinities of Mr. Proust's accomplished villain.

Now this is not to say that these things are not good of their kind. There are passages of Ulysses that I shall be glad to my last day that I have had the opportunity of reading and remembering. I_ cling to the skirts of Miss Richardson's Miriam and wait eagerly for the next volume. The early volumes of M. Proust's enormous book give one splendid riches in retrospect, but when Mr. Murry and the others talk about the break-up of the novel I beg deeply and perpetually to differ. When they talk, too, of these recent books as being manifestations of something perfectly new and strange, I beg there also to differ.

The Novel vs. Autobiography

WHAT is it that the novel does better than any other of the arts? It creates people and it reveals their ambitions, their tragedies, their triumphs and their humors. When it creates people and moves them about in juxtaposition the one with the other a story forms. No human being can be for five minutes in contact with any other human being without there arising from that contact some sort of history, but this thing must be created. Flaubert was Flaubert with all his vexed and tortuous personality thick upon him, but he created Salambo and Emma Bovary. Dickens wore loud waistcoats, was the most restless man alive and loved amateur theatricals, but he created Mr. Dick and Traddles. Walter Scott was a quiet, unsuspecting country gentleman, but he created Nantie Ewart and Effie Deans. Now what are Dedalus and Mr. Bloom but Mr. Joyce himself? What is Miriam but Miss Richardson? What is M. Proust's thick, glorious tapestry but his own so deeply charged, so richly invested reminisences?

(Continued on page 112)

(Continued from page 34)

These books which, Mr. Murry claims, represent the break-up of the English novel, are not novels at all; they are autobiography just as surely as were the Journal of Marie Bashkirtseff and the confessions of St. Augustine and the revelations of Jean Jacques Rousseau. Moreover, the claim of these books to be realism is false. It has become now the determined philosophy of the new writers that realism is truth, and that truth can only be absolutely known through personal experience. The moment then that you step outside the narrator s own brain in order to collect evidence, you are writing falsely; imagination then is denied, it is too dangerous, and we have instead all the realistic rebellions of the narrator who is hunting desperately through the annals of his past and his present to discover something interesting enough to be presented. Sometimes there is nothing of sufficient interest. What then? Well, we must have something to fill up the page.

The soap dish is there, the -shabby wall paper is not far away, the windows misted with rain are close at hand, there is the smell of beef on the melancholy stairs.

When a man of Joyce's size comes along, anything that he does is interesting, but it is the individual that affects us and not his disastrous pulping of the English novel. That still, I am glad to be able to inform my friends, is alive and even kicking. In England Frank Swinnerton, Miss Kaye Smith, Francis BrettYoung, and many others are producing work interesting, alive and modern enough to hold our attention, and in America there are, of course, Edith Wharton, Joseph Hergesheimer, Sinclair Lewis, Willa Cather, Dorothy CanfieldFisher, and many, many more, all using the novel as something that is more than a subjective account of personal experience, all creators in the sense of that word that is as old as the hills and as modern as the tallest sky-scraper.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now