Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Oldest Golf Club in the World

An English Player Mourns the Melancholy Passing of the Royal Blackheath Club in England

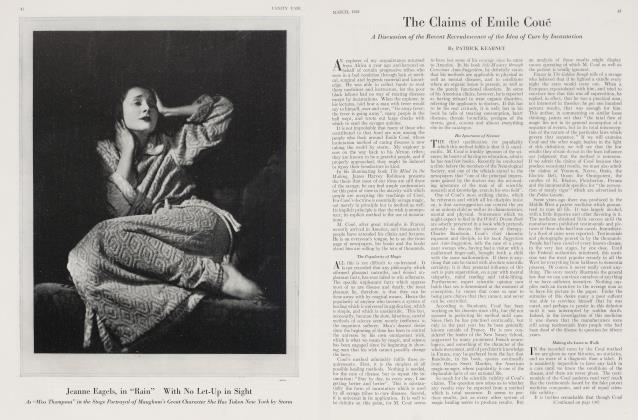

BERNARD DARWIN

IT may interest Vanity Fan's American readers to know that golf at Blackheath will henceforward be only a memory, and since the game has been played there from the time when James I first brought the game to England with his Scottish Courtiers, and since the Royal Blackheath Golf Club is the oldest golf club in the world, one may be allowed, I hope, to shed a sentimental tear over it.

The Club itself, I rejoice to say, will not die. It will keep its proud name and tradition, its pictures and treasures. Negotiations are now pending between the Club and the Eltham Club nearby, which has a very pretty pleasant course, and though all is not yet settled, one may safely say that the two Clubs will join on the Eltham Course under the time-honored name of the Royal Blackheath Golf Club.

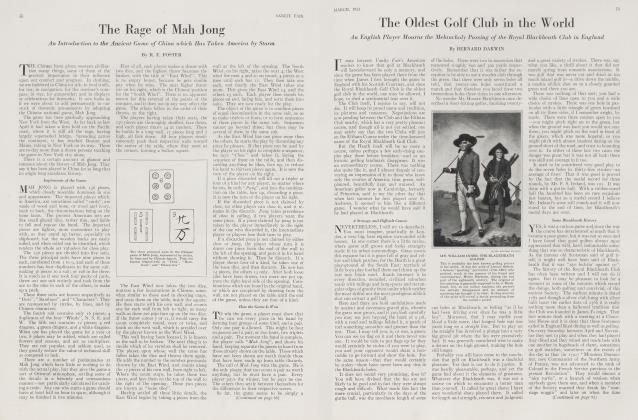

But the Heath itself will be no more a course, unless perhaps a few early-rising couples play there before breakfast—and so an historic golfing landmark disappears. It was an extraordinary course. There was nothing else quite like it, and I almost despair of conveying an impression of it to those who know only the courses of America, trim, green, wellplanned, beautifully kept and watered. An American golfer now at Cambridge, formerly of Princeton, said to me the other day that when last summer he first played over St. Andrews, it seemed to him like a different game. I wonder what he would have said if he had played at Blackheath.

A Strange and Difficult Course

EVERTHELESS, I will try to describe it. You must imagine, practically in London, a very big, bare expanse surrounded with houses. In one corner there is a little ravine, where gorse still grows and looks strangely rustic in its urban surroundings. Grass covers this expanse but it is grass full of gray and yellow and black patches, for the Heath is a great play-ground of the South East: myriads of little boys play football there and churn up the turf into black mud. Roads intersect it in every direction, metalled, civilized suburban roads with railings and lamp-posts and rectangular edges of granite from under which neither the most skilful nor the most prodigious niblick shot can extract a golf ball.

Here and there are bold undulations made by ancient and cavernous gravel pits, wherein the grass now grows, and if you look carefully you may see just beyond the bank of a pit, with a road and railings behind it, a patch of turf something smoother and greener than the rest. That, I may tell you, is, or was, a green. You can see no flag on it and there never was one. It would be vain to put flags up for they would certainly be stolen: if you were to play, you and your opponent would share a forecaddie to go forward and show the hole. For the same reason—that they would certainly be stolen—there have never been any tins in the Blackheath holes.

It does not sound very promising, does it? You will have divined that the lies are not likely to be good and in fact they were always rough and difficult. What made this fact the more crucial, particularly in the days of the guttie ball, was the inordinate length of some

of the holes. There were two in succession that measured roughly 600 and 500 yards respectively. Remember that it was rather the exception to be able to use a wooden club through the green, that there were only seven holes all told, that twenty-one holes constituted a match and that therefore you faced these two tremendous holes three times in one afternoon.

No wonder Mr. Horace Hutchinson once described a short-hitting golfer, finishing twenty-

cne holes at Blackheath, as feeling "as if he had been driving ever since he was a little boy". Moreover, that I may curdle your blood a little, more, that longest hole was 600 yards long on a straight line. But to play on the straight line involved a plunge into a very big gravel pit where the lies were excessively bad. It was generally considered wise to make a detour on the high ground, making the hole still longer.

Probably you will have come to the conclusion that golf on Blackheath was a doubtful pleasure. Yet that is not to do it justice. It was hardly pleasurable, perhaps, and yet the game had about it the elements of greatness. Whatever else Blackheath was, it was not a course on which to encounter a better man than yourself. It called for great shots: I have seen wonderful shots played there. It called for length and strength, resource and judgment

and a great variety of strokes. There was, say what you like, a thrill about it that did not merely spring from romantic associations. It was golf that w'as never cut and dried as too much inland golf is—a drive down the middle, a mashie niblick shot on to a closely guarded green and there you are.

There was nothing of that sort; you had a wide choice of lines open to you and a wide choice of strokes. There was one hole in particular with a little triangle of green bordered on all its three sides, if I remember aright, by roads. There were three courses open to you —you might pitch right on to the green, but when the ground was hard you would not stay there; you might pitch on the road in front of the green, which was more hopeful; or you might pitch with almost insolent daring on the ground short of the road, and trust to bounding over it. In either of these last two cases the danger was great but it was not all luck: there was skill and courage in it too.

It used to be considered very good play to do the seven holes in thirty-five strokes—an average of fives! That it was good is proved by the fact that the medal record for three rounds, by Mr. F. S. Ireland, was IOI. It was done with a guttie ball. With a rubber-cored ball the hundred has been on rare occasions just beaten, but as a medal record I believe Mr. Ireland's score still stands and it will now stand to the end of time, for Blackheath's medal days are over.

Some Blackheath History

YES, it was a curious game an since the war the course has deteriorated so much that it became a poor game, but it was not so once and I have found that good golfers always most appreciated that wild, hard, indomitable something that was so characteristic of Blackheath. As the famous old Scotsman said of golf itself, it might well have been said of Blackheath that it was "aye fechtin' against ye".

The history of the Royal Blackheath Club has often been written and I will not do it again. But it may be pleasant to look for a moment at some of the minutes which record the doings, both golfing and convivial, of this ancient Society. The earliest minute is dated 1787 and though a silver club hung with silver balls bears the earlier date of 1766 it is really nothing more than a hallowed tradition that the Club was founded in James I's reign. That first minute dealt with a meeting at a Chocolate House and it is clear that these Scotsmen exiled in England liked dining as well as golfing. On every Saturday between April and November they met to play and when they had played they dined and they wined and made bets with one another in hogsheads of claret, sometimes on golf matches, sometimes on the events of the day as that (in 1792) "Monsieur Dumourier, now Commander of the Northern Army of France, was not advanced to the rank of Colonel in the French Service previous to the present Revolution". They would discuss a "nice turtle", or a haunch of venison when anybody gave them one, and when a member of the Society married they drank his "marriage noggin" and later on when the time came, the health of the "young golfer" or "golferess" that resulted.

(Continued from page 73)

(Continued on page 92)

Anything was a reasonable excuse for good cheer. For instance we find that in 1800 "Mr. Callender having taken the keys of the Golf Box to Ramah Droog Castle Captain Langlands desires notice to be taken of the same, and as wine does wonders a gallon of course follows". A great man was this Mr. Henry Callender who was granted a special honor "by placing upon his shoulder an additional epaulet, and his health under the appellation of Captain General was drunk with great applause". There is a striking picture of him by Lemuel Abbott. There he stands a fine figure in red coat and white breeches and the two epaulets (other Captains had but one) extending to you a stately welcome as you come into the club. Captain Langlands, too, was a person of importance for in 1797 it is gravely recorded that he "holed the long Hole in six strokes and the wind N. E. stiff breeze". Probably he had five full drives with his feather ball, and then holed a long putt.

Another Captain of the Club to be painted by Lemuel Abbott was Mr. William Innes. This is probably the best known golfing picture in the world. There are endless prints of it: we all know Mr. Innes with his red coat and blue facings, and his single epaulet (he was not a great enough man for two), and his caddie with the suspicious-looking bottle protruding from his pocket. Nearly everybody believes that the original picture is at Blackheath, but alas! it is not, nor have the most searching inquiries discovered where it is. Probably it was burnt in the fire long since, which is believed to have destroyed many of the Blackheath records. There is a curious and interesting picture at Blackheath painted in imitation of it. Who Mr. Francis Bennoch was beyond that he was Captain in 1860 I do not know, but he had himself painted in the Innes style with caddie and bottle complete, and so became immortal.

But of all these old worthies the one that I find most intriguing was Mr. Gotlieb Christian Ruperti. Who he was nobody now knows, but very clearly from his name he was no Scotsman. However, he was a jolly and convivial person, and used to present the golfers with admirable haunches of venison. Possibly it was thus that he first found his way into their select company. At any rate he so endeared himself to them that they made him Captain in 1812, and then what splendid hospitality was his. Not only did he induce his Serene Highness the Duke of Brunswick to dine with the club, but he induced the club to give a public breakfast "to the ladies and gentlemen of the Heath and its neighbourhood". There were soldiers to keep the ground, a military band to play, and tents erected on which fluttered proudly the club flag. The ladies had a "cold collation". After that the gentlemen, who had apparently been partaking of their gallons in privacy, joined them and "the scene then became truly interesting from so large an assemblage of ladies and beauty and fashion. Swift footed Time soon beckoned it is the hour to part, and after the Band played 'God save the King'—the ladies took their leave with regret, but with countenances that bespoke a lively remembrance of the happy hours they had spent." The ladies once' safely out of the way there was a tremendous dinner with the Duke of Brunswick again, and another haunch of venison, "from the Duke of Rutland's Park". Bravo! Mr. Ruperti! Those old Scotsmen probably thought you foolishly extravagant, but no doubt they did justice to your good things.

This fine tradition of cheerful hospitality has always been maintained at Blackheath. The Annual Dinner of the Club is a great occasion, with Pipers marching round the table, the Field Marshal and the Captain, and the past Captains in their red dress coats and a silver quaich from which whisky is drunk—this last a pleasant and solemn ceremony, which coming in the midst of champagne is yet apt to be deleterious. All these things will doubtless be maintained, when the Club moves finally from its storied Heath, for it is justly proud and tenacious of its position and traditions. And it deserves all honor, not only on their account, but because when golf first invaded England, and sprang up at Westward Ho! and Hoylake, it was in every possible way fostered and encouraged from Blackheath. In earlier days, too, the club had written grave letters of congratulation to those who spread the game in the East, even as far as in Dum Dum, Bombay, and Calcutta.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now