Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

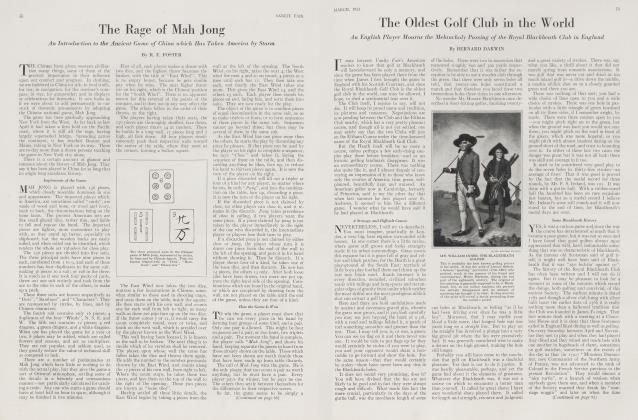

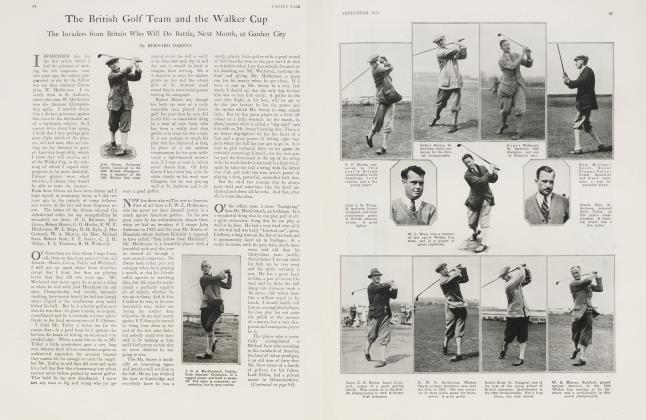

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA great English golfer: John Ball

BERNARD DARWIN

Two months ago, British golfers had the opportunity of wishing not only a merry

Christmas but also many happy returns of his birthday to a great player. Mr. John Ball was seventy-one years old.

It would be pleasant to think that on that day he came over to Hoylake not far from Liverpool (he now lives over the Welsh border) and played a foursome with three chosen friends.

I do not know if he did; but, if it was so, I am sure of two things: first, that he came there secretly, like a thief in the night, avoiding all notice; and, secondly, that all of Hoylake who saw him went nearly mad with joy. There are many golfing shrines and all have their deities but there is no shrine that has such devout worshippers as Hoylake, and no deity such as he who was once called John Ball Tertius, then John Ball Junior, and now John Ball.

To no other great game player, always excepting W. G. Grace, in English cricket, has it, I think, been given to become so legendary a figure in his own lifetime. The golfing world is full of John Ball stories, and I read them periodically in American newspapers, where they are not always very accurate. This is the more remarkable because few men have ever said less, at any rate, in public, and no man has ever made more resolute efforts to shun publicity. Yet when he does speak, his words have some quality that fixes them in men's memories. Go to Hoylake to-day and talk to any old members of the Royal Liverpool Golf Club, and you will be told how John, having played in a hurricane of wind and having won the medal by some fantastic margin, explained that he had "happened to be hitting the ball at the right sort of height for the day". Talk to a younger member, and he will tell you that "Old John" does not like the new bunkers which he thinks are too easy, that he calls them scornfully "geranium beds," and likes a bunker that "makes you scratch your head to see if you can get out".

John Ball was a great figure on any links he trod, and he has the distinction of being, I believe, the only honorary member of the Royal and Ancient Golf Club. But (first, foremost and all the time), he has been a Hoylake golfer. It was there he was born, when it was no more than a Cheshire village, difficult to reach from Liverpool, with a hotel, a race-course, a rabbit warren and not much besides. In 1869, the club was founded and one of the first members was our hero's father, then Mr. John Ball, Junior. The Ball family owned the Royal Hotel, over against the present seventeenth hole, which is called the "Royal", and for many years the club used the hotel as its club-house. It was natural that a small boy living on the edge of the links should play golf, and, in 1872, when he was eight or nine years old, came his first success: he won the Boy's Medal. That was the forerunner of his ninety-four scratch medals of the Royal Liverpool Golf Club.

In a very short time, he became an outstanding player and he was almost as precocious as Bobby Jones. When he was fifteen he went up to Scotland, chaperoned by Jack Morris, the Hoylake professional, and got into the prize list; I think he was sixth. I have heard him say that he could play better then than he ever did afterwards. That was a slight exaggeration, but no doubt he attained to excellence at an extraordinarily early age. No wonder that his father, who had become a very sound and steady player in an unorthodox style of his own, often made the bare parlour at the Royal ring with the challenge, "Me and my son'll play any two". That was a day of few courses and of a freemasonry among golfers that sent them on friendly pilgrimages to other links. The best Scottish amateurs would come adventuring to Hoylake, and there was the young John ready to send them home again with their tails between their legs.

Hoylake thought unutterable things of its young champion, and yet there was a time when it had to tear its hair with grief because he could not do himself justice.

He played a home and home match against Douglas Rolland, a stone mason from Elie, afterwards a famous professional, and was badly beaten. That was a blow and there were more to come. In 1885 there was promoted a tournament at Hoylake which has since been retrospectively canonized as the first Amateur Championship.

John Ball, incredibly, did not win. In the next year the Championship proper was founded at St. Andrews: he reached the semi-final and was beaten to pieces by a player who never ought to have held him. In 1887, it came back to Hoylake and Horace Hutchinson beat him in the final, beat him on the home green before his own front door.

Then the tide turned, and gradually the man who could not do himself justice on the great occasion came more and more to be reputed the man for the great occasion, for a long-drawn-out spurt, for a forlorn hope, against whom it was never safe to bet till he was actually beaten.

In 1888, he won the Amateur Championship for the first time and he continued to win it off and on till 1912, when at Westward Ho! in a memorable match, he beat Abe Mitchell, then an amateur, on the 38th green. In the course of those twenty-four years, he had won the Championship eight times, a record that no one else has approached.

Moreover, he had done something else: in 1890, an Englishman and an amateur, he had the audacity to go to Prestwick in Scotland and win the Open Championship against the Scottish professionals. No Englishman had ever won it before: only two amateurs have done so since, one of them being Bobby Jones, who has won everything; the other is Harold Hilton. It was an epoch-making event and well might Dr. Laidlaw Purvis, a fine old Scottish golfer and the founder of Sandwich, say to Mr. Hutchinson in (Continued on page 72) tones of ineffable solemnity, "Horace, this is a great day for golf."

(Continued from page 51)

John Ball never won the Open again though he was often very near to doing so. Had he been a professional— and there never was a more complete amateur—he would, I fancy, have won several times more, for everybody who ever saw him agrees that he was one of the great golfers in the game's history. To my mind he had, beyond all argument, the most beautiful swing that ever was seen, and it was all swing, the quintessence of rhythm. If I try to describe it it does not sound beautiful, for he stood with a very wide straddle and legs notably stiff, and the handle of the club appeared to be sunk deep in the palm of his right hand. In fact, that was an optical illusion, for he held it in his fingers and there was no look of stiffness in his stance, only one of extraordinary firmness and balance, so that if somebody had pushed him suddenly from behind he would still have been immovable as a rock. Moreover, his wide straddle did not prevent his having the smoothest "pivot" imaginable; in every movement he was rhythm personified.

As I said before, John Ball had an immense reputation for pulling matches out of the fire and it was richly deserved. He could be nervous and I have seen him when his fingers almost refused to take the paper off a new ball, but it was at just such a moment that he would produce a thrust not to be parried. He was sometimes a lazy starter but his spirits seemed to rise gleefully when he was three down, and, if it is possible for anyone really to enjoy a close finish, he did so. This slow starting grew on him, I think, with age and was the despair of his Hoylake admirers.

Year in and year out, though he lived on the links, he did not play a great deal of golf, except, I suppose, in his early youth; but the club remained a familiar thing in his hand. No Hoylake picture comes more readily to mind than that of John walking across from the Royal to the club, with head down and knees bent, chipping a ball along before him as he went. When a big event was drawing near he would go out with a club or two and practise shots—not the orthodox shots, but queer shots from queer places. An evening or two thus spent in solitude with a club seemed to be all the practise he ever really wanted; that perfect machine needed wonderfully little oiling.

He still plays, now and again, a carefully chosen foursome in which sly jokes and friendly insults can be exchanged. Four or five old clubs with wooden shafts supply all he needs for these games, and though a contraction of some of his fingers now makes it hard for him to grip the club, and he is not quite so lissom as of old, much of the old swing is still there. If only I were quite sure I could see all of it again, nothing should hold or bind me; I would pack my bag this moment and take the very next train to Hoylake.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now