Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe caged white woman of the Saraban

WILLIAM SEABROOK

EDITOR'S NOTE: This is the second of a series of African sketches for VANITY FAIR by William Seabrook, author of The White Monk of Timbuctoo, and other books. Last month, he told the story of Helene, the school-teacher's daughter in Administrator Briolle's province, and her French doll. In this chapter, Briolle ponders a more taxing racial puzzle.

No roads or regular safari trails led up into the Saraban, and no white Frenchman of this decade—not even Briolle—had ever penetrated beyond the mountain.

Yet repeated and roundabout gossip kept seeping down to the Ivory Coast and finally became disturbing to administrative ears, since the Saraban, though merging into the hinterland of Liberia, was technically French territory.

My friend, Andre Briolle, eccentric and cynical tyrant of Douékué, whose back door touched the Saraban, was more petulantly annoyed than actually disturbed; for if there is any one thing, other than sunstroke, that gives your seasoned African colonial a sharper pain in the neck than something else, it is precisely any tale, rumor or gossip about white goddesses, mysterious golden haired captives, blonde, voodoo high-priestesses; lost, strayed or stolen heiresses and chorus girls, engulfed by the "Dark Continent," all the way from Rider Haggard's She to Benoit's Antinea.

The queer, persistent rumors from the Saraban were in this silly category, and might have been completely discounted had it not been that it was the natives themselves, the Yafoubi and Ouabe, who kept the rumors alive; insisted they were true. They said that there was a man up there, on the banks of the Cavally, on the other side of the mountain, who kept a woman with long, flame-colored hair in an iron cage, "kai gaibou": that is, "like a panther,"— like a wild beast in an iron cage—and Dioula peddlers, who claimed to have actually seen the woman, swore she was a white European.

"It could be," Briolle said, "that it is a drawing or a painting that has taken hold on the imagination of some isolated tribe back there; it could be a wooden image or idol; the woman could even be some animal, or even a stone, or a tree. When you live here in the jungle ten years, you begin to understand that what you first mistook for malicious fantasy, insane, deliberate lying to mystify us whites, is often something different and quite sincere. You think, when you have learned Malinké, Ouabe and Bambara, that you speak their language. But, my friend, it is deeper than that. No white man will ever speak their language. Not even I, Briolle, can speak their language, though I know more dialects than most of my black interpreters. My Senegalese butler who served four years in France, who can take my motor to pieces and put it back again, who has a phonograph and can read the Morse code, once took me to see his grandfather at Daloa, and his grandfather was a goat! My Ouia, who has more hard, common-sense, as you know, than nine-tenths of the white functionaries down in the governor's palace, keeps a seashell which is her dead sister. Half the time, to them, a tree is not a tree. A broken monkey-wrench you've thrown away is a snake —or somebody's cousin.

"That's what bothered that professor back in Paris, Lévy-Bruhl! I don't suppose he's ever seen a savage, let alone talked with one, but he's written some chapters on animism which touch it pretty closely. But he's only touched the edges. There's a point at which it begins to tangle with their magic, and there, no white mind can follow it. In that sphere, a man's way of wearing a hat can be a crucified man or a herd of elephants. Yet that white-haired old idiot down in Bingerville (I regret to say Monsieur Briolle meant His Excellency the Governor) has been badgering me to run down this particular piece of fantasy. Mind you, the whole tale is purely native. Bah!"

Thus Briolle rationalized the story from the Saraban, to his own cynical satisfaction —and forgot it. "Besides, you'll find," he had concluded, pouring us another dose of the home-distilled Pernod to which his fellow administrators swore he added powdered caterpillars as the negroes do, "you'll find that flaming queens in iron cages, whether in Europe, Africa or Iceland, are always on the other side of the mountain, no matter which side you happen to be on yourself."

I wasn't quite so sure about all this. It seemed to me that the tale's being purely native, which he made the main reason for discounting it, suggested possibilities which he had overlooked.

Well, time passed, Briolle and I quarreled—we were always quarreling about something—then patched it up as usual, and, one day, hearing that the rivers were fordable again, I rolled out of the region in the old Citroen truck, bearing eastward, vaguely toward Lake Tchad, which, by the way, I never reached.

Some months later I was in Bouaké, back on the edge of the forest again, adjacent to Briolle's region, wanting to see him anyway, when I got a franked official telegram, signed "affectionately,"—he loved to be derisive—and inviting me back to Douekue.

I needed no urging. When I rolled into his compound two evenings later, he met me grinning like a crocodile. That, by the way, was the nickname his negroes had given him, with a mixture of loving pride and wholesome fear. Colonel Bamba, they all called him, often to his face, "Colonel Crocodile."

"Hein," said he in his ironic, nasal voice, "so you couldn't reach Tchad! I told you you couldn't, not in this season, with that old tacot. You were a fool to try."

"Thanks," I said, "but you didn't send for me by wire to tell me that."

"Why, no, my friend, I just wanted to see you. I was lonely."

"Well, abuse me," I said, "I hope you enjoy it, but what else? Are you going to take me hunting?"

"I'm going to take you over the mountain. I have to go, finally, and I knew you would be just the idiot to come along with me. If I weren't a fool myself, we wouldn't be going. But I have to go. I've got a Dioula here, a peddler from the north, a Mohammedan, who was selling silks and colored leather down the Cavally, who swears he not only saw, with his own eyes, but talked with a white woman in an iron cage up there, while she was choosing some of his silks, if you please! and that she spoke in French. I don't believe this man either, but I have to go. And I knew you would come along with me."

We had dinner on his terrace. I had brought Ouia, his superb black mistress, a pair of soft-gold Timbuctoo earrings which she was trying to fit to her toes. I told Briolle that I would be delighted to go.

"Well," he said, "we'll find no caged woman, of course, but I'll show you more baboons than you ever dreamed were in the world. We had a telescope trained on that mountain a couple of years ago when the chief surveyor was up from Bingerville, and the rocks were swarming with them like maggots in a cheese."

Next day one of Briolle's trucks took us to the base, and by late afternoon we were up among the apes. We packed light, afoot, with his cook, his boy, and six porters. The ridge lay like the gray carcass of a whale, emerging from the green junglesea, and its clefts literally swarmed with baboons. It was a baboon metropolis. On some slopes, they were thick as flies. Briolle and his negroes treated them like people. They were quite harmless, so long as we remained polite,—and not afraid of us. They chattered with interest, but not in anger. He said that if we killed or wounded one, they'd submerge us and tear us into little pieces.

We camped that night on the further slope, above the Cavally, and in the morning a petty chief appeared, with a dozen men, armed with spears, drawn by our smoke, to see who we were and what we wanted. They were Ouabe, like Briolle's own negroes. We went down with them, gave them two or three salt bars and some tobacco. They found us a pirogue (dugout) above the rapids, and manned it with paddlers. We went for three days up the river, Liberia lying on our left. On the fourth day we came to a worked mahogany clearing, and soon to a prosperous plantation, in a lagoon, on the French side. It looked normal, ordinary, commonplace. It couldn't conceivably be what we were looking for, yet the paddlers said it was. We tied up, and, as we were unloading, the proprietor came down to the water. He was a surly but not stupid-looking fellow, black-bearded, middle-aged—a Frenchman, Luxembourgeois, it turned out. He was arrogant and not glad to see us. It is a mistake to be arrogant with Briolle.

(Continued on page 71)

(Continued from page 31)

He said: "So here you are, playing that old game in my district! One foot in Liberia, the other in French territory, cutting mahogany on both sides of the river, evading taxes, paying no concession! I am Briolle, you understand, administrator-general of this district, and, they tell me, you keep women in cages!"

At this, an extraordinary change came over the bearded man. It was not so much that he wilted. His face showed sudden surprise, slow comprehension, then softened to a queer, bitter expression.

"Ah, monsieur," he said in a new tone, "so that is it. So you are the administrator. A thousand pardons. It is just as well that you came. I beg you to come to my house. It is true, yes. Dreadful as it may sound, I keep my wife—in a cage. And if I did not keep her behind bars, where she cannot break out nor others break in, she would not survive!"

Briolle is a difficult man to astonish, but his mouth had dropped.

"No," exclaimed the planter earnestly, "I am not mad, nor my wife insane in any ordinary sense. I do not know what you believe about such things, but my wife is demoniac, possessed."

We had reached the veranda. Houseboys brought trays with refreshment. We stood uncomfortably. Briolle said:

"I have lived for twelve years in the jungle. ... I do not know what I believe."

Here, concisely, is the tale the man told us, with its evil roots not in the jungle, but back in the center of civilized France:

He had met the girl in Lyons, where she taught in the Ecole Normale. She had seemed strange to him from the first, but wonderfully so; he had fallen in love with her—was still in love with her, despite everything—and they had married. It was only after he had brought her to the colonies—and after the first dreadful thing had happened here in the jungle—that he had learned the true nature of her strangeness. Lyons is, of course, the modern stronghold of deep, mediaeval Catholic mysticism in France, and many an ancient coin, though it be of purest gold, is stamped on its reverse side with an obscene image. It is always in profoundly religious communities like Lyons that Satanic cults, demonology, black superstition, witchcraft thrive. Not many years ago the French newspapers stirred up a terrific scandal about the Black Masses which are still celebrated, periodically, in the city on the Rhone. Well, this girl had become secretly tangled with the Satanists, had become an adept, an illuminée, had lain naked on an altar back in Lyons, had given herself to the Demon. Though her husband had known nothing of it, she had been for years a Bride of the Abyss, had feared and hated it in her normal intervals, and it was to escape that evil environment, that she had married him and come with him to the colonies.

After they had come down through Sierra Leone and settled on the Cavally, her husband, ignorant of all this, had taken her one night to see a tribal tomtom ceremonial—the Ouabé, here in this region, are always as pleased as children to welcome whites to their ordinary Fetishist ceremonials because the French have maintained a strict policy of never interfering with their rites or religion so long as no criminal law is violated. It was an ordinary invocation of their jungle gods and demons, with drums, masks and dances. But just as the blacks were reaching the peak of their usually harmless frenzy, the white girl had suddenly begun screaming, had torn off all her clothing, had rushed into their midst, galvanized, illumined, shrieking, calling "Sathanas! Sathanas! Ashtoreth!"

Then a worse thing had happened. The natives, abandoning their own masked witch doctors, had milled around her, falling at her feet, throwing themselves in her path so that she would trample them, howling "G'nouna! G'nouna! G'nouna!", which is the feminine incarnation of Gla, the Great Demon of the Forest. They had put a staff in her hand and as she beat them with it in her frenzy, they had fought with one another to receive the blows, for a man or woman maimed, even killed, by Gla Incarnate, is privileged, forever sacred; becomes a minor tribal power, alive or dead.

She had fallen unconscious, the witch doctors and her husband together had extricated her from the milling mob. She was ill with fever for a week. The husband had nursed her, had supposed it was a fit of temporary madness induced by the rhythm of the drums which indeed sometimes drive whites mad. But then, one night, when the drums began again down by the river, she was gone from her bed. This time the witch doctors brought her back. She was rigid, cataleptic and unclothed. And one of the witch doctors, speaking in Bambara for the rest, had spoken. Fear for their own prestige, of course, was at the bottom of it. They were afraid of her. They didn't want her. He must keep her, restrain her, hold her, they told him solemnly. If she came to them again, they said, they would not answer for the consequences. Their meaning was plain.

This time, when she returned to consciousness, she had confessed everything to her husband. She herself believed she was demoniac, still feared and hated it, as she had at last in Lyons, begged her husband to protect her—from herself. She was afraid to go back to Europe, for wherever they went, she feared, the cult would find and claim her. So they had contrived the cage. That was all, the planter told us,—except that, as the black Mohammedan servants he had brought from Sierra Leone had heard whispers from a neighboring village he had strengthened the cage, and kept a man always on w'atch in the compound.

Yes, the cage was here, in the compound, adjacent to the house. We would go there now. And Monsieur the Administrator would do what he judged wisest.

(Continued on page 73)

(Continued from page 71)

So we went. And there it was, just as the Dioula peddler had said—the white French woman locked in an iron cage, kai gaibou, like a panther, like a wild beast in the zoo. As for the cage itself, it was roofed, comfortable, clean as a room, built sheltered against the bungalow, with mats on a hard earthen floor, a divan in one corner, piled with cushions, and, in another comer a shower and rudimentary toilet arrangements much the same as Briolle had in his own house in Douekue.

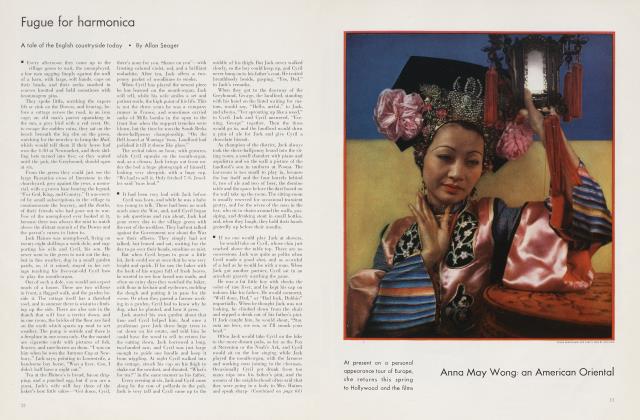

As for the woman who came forward to the bars, sullen but unembarrassed, wrapped in a silk pagne, twisted round her body in the Arab manner, inhaling deeply a cigarette, she was unpleasantly beautiful, a curved, nervous creature with fiery, red hair, big, green, animal-like eyes, pale, definitely neurasthenic.

"My wife, Marthe," said the planter, making the weird introductions. But the conversation refused to begin. Briolle sought refuge in official formality.

"Madame, I am the administrator general with full police authority in this district. I have men with me. I take note of what I see in the presence of this gentleman as witness. I take note and am ready to act. I am at your service. Do you make complaint against this man who says he is your husband? Are you held here against your will? Do you wish to be released first and then charge him?"

The woman inhaled again deeply and stared at Briolle.

"He is my husband," she said. "I don't know, Monsieur the Administrator. You'd better talk with him about it. He'll tell you the truth about it. I don't know."

"As you wish, Madame," said Briolle, saluting punctiliously.

We were half way down to the rapids next day, sliding with the current, in the pirogue, when Briolle said:

"It looked crazy, but it wasn't a stupid idea you know. I've learned something myself about black magic in twelve years down here. It has evil power, make no mistake. It can make a man believe he's a panther, it can make him ill, it can waste him away to a skeleton, it can kill at a distance as surely as a bullet. It can even, perhaps, blast a tree or plant, though I'm not sure about that. But human beings and trees are animate, organic. Against the inorganic, on the contrary, magic is powerless. No demon, no magic, can knock down a wall, move a mountain or a stone. And no magic, my friend, can twist or break an iron bar. The Luxembourgeois, my friend, are practical people."

When we got back to Douekue, Briolle had the Dioula peddler beaten publicly, gave him a handsome present and some good advice privately, then went around strutting and saying:

"Bah, of course it was nothing! Just another piece of superstitious, nigger imagination.'! was a fool to go. But those baboons yonder, on the mountain, do you know. . . ."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now