Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

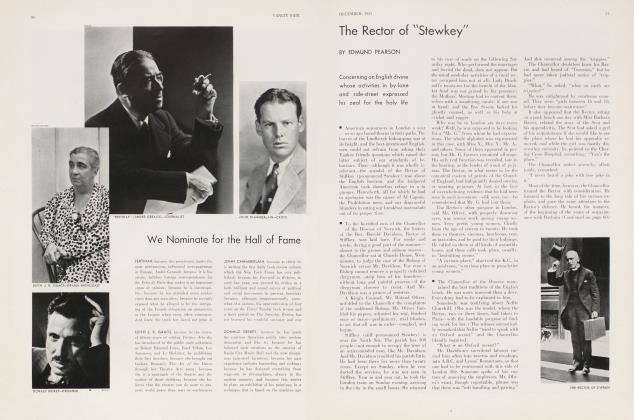

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowCalifornia's "Bluebeard" Watson

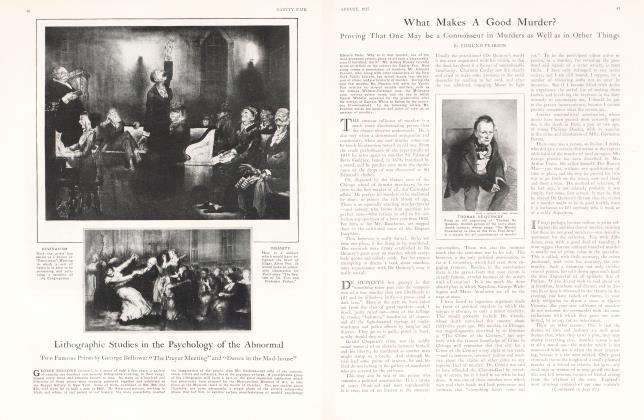

"Holmes, this is marvellous!"

"Elementary, my dear Watson!"

How often have the parodists of Conan Doyle repeated these imaginary remarks, supposed to have passed between the great detective and his eminent stooge!

In London, when Holmes and Watson set out together in a hansom (Watson with his old service revolver in his pocket), it was well for criminals and evil-doers to hunt their holes.

The curious fact seems to have escaped, not only the devotees of detective fiction, but also that select class of readers who enjoy old tales of real crimes, that these revered names, Holmes and Watson, were also adopted in America by two sons of Satan, who enlisted not under the flag of the children of light, but under the banner of the foul fiend.

Mr. Holmes of Philadelphia, and Mr. Watson of Los Angeles seem to have been America's most lavish devotees of the appalling habit of wholesale murder.

When the hangman in Moyamensing Prison conducted the former of these men to his just punishment, it had been discovered that his real name, as entered on the rolls of the Universities of Vermont and Michigan, was Herman W. Mudgett. He had done well to adopt the steely title of H. H. Holmes; it was better-suited to this lanternjawed person who strolled about the country, slaying the old and the young, and who kept in Chicago a strange building, called "Holmes' Castle," where pretty typists sometimes entered, never more to be seen by anyone, except as well-articulated skeletons dangling in a row in the closet.

The career of "Bluebeard" Watson even more fully deserved the attention of the great investigator of Baker Street. After the law officers and reporters of California had uncovered enough of his rascality to hang about eleven men, they rested from their labors. They were all out of breath. During four exciting weeks the District Attorney of Los Angeles County had not ceased to tear his hair. Every morning, the good Angelenos turned to their Examiner or their Times to see under what new name Mr. Andrews (alias Hilton, alias Gordon, alias J. P. Watson) was in possession of bankbooks or marriage certificates. Each noon-day train brought down to the City of Our Lady Queen of the Angels another indignant woman from San Francisco or Sacramento or Seattle, full of well-justified suspicion that she was one of the multitude of wives of the mousy little fellow then fidgeting in the County Jail. And each eventide, half a dozen men, named Gordon or Harvey or Lawrence or something else, telegraphed in from Florida or Massachusetts or Ontario or Kansas to protest because they were being confused with the "monster" whose grisly exploits in the lonely canons west of San Diego were slowly coming to the light of day.

In the spring of 1920, in that pleasant section of Los Angeles called Hollywood, there dwelt a lady of austere mien, named Kathryn Wombacher-Andrews. Mr. Wombacher had passed from her life, by act of God, or Court's decree—I know not which—and now Mr. Andrews, her second husband, began to mystify her by absences of two weeks at a time.

Like many other innocent persons who have unconsciously stood on the brink of the steaming pit of Sheol, Mrs. WombacherAndrews did not look the part. Had you met her on a street-car, and observed her rather ascetic countenance, you would have concluded that she was on her way to address the Woman's Club of Pomona, on "Helen Hunt Jackson: Her Place in American Literature."

You would not have guessed that she was about to consult the Nick Harris Detective Agency, and thereby raise the lid off a very active section of Hell.

She had no special complaint against her husband, so she told the handsome Mr. Nick Harris. She just wanted to know why an employee of a trust company in British Columbia (as he had assured her he was) should now and then vanish for a fortnight.

"He is always a gentleman," she said. "Remember that. He is a clever man, and intellectually bright. We met in Seattle. I was a business woman, and tired of living alone. So we were married last November. At Christmas, his Company transferred him to Los Angeles; so we moved here."

Mr. Harris began his search, helped by the police, and soon picked up Mr. Andrews, who had—quite unjustly—become suspected of a bank-robbery. The officers, immensely interested in the contents of his valise, altered their suspicions to burglary and then to bigamy. They might have proceeded to barratry and even bigotry had not the reticent prisoner given indication that he had something really serious on his mind. He did this by an unsuccessful effort to cut his throat with a pen-knife.

This happened during what the elated reporters called a "night-ride" to San Diego. Police officers were conveying him thither to discover the truth about all these bankbooks, held in the names of "Walter Andrews," "H. L. Gordon," "C. N. Harvey," et al., and carried in his baggage, together with some marriage licenses, indeterminate in number, but thought by the police to be excessive.

EDMUND PEARSON

While he was recovering from the slight wound in his throat, and while the newspapers, after many suggestions, were fixing upon his name as "J. P. Watson"—because it was as good as any other—there was much running to and fro, much gossip of this and that, and a few modest admissions by the diffident little polygamist himself.

The District Attorney became aware that he had in his keeping one of the most widely married men of all time, whose seraglio was scattered from the Canadian provinces to the Mexican border. Many of these ladies were still fretting out their days in the light of the sun, but an amazing number of them had been stealthily buried by the prisoner.

Mrs. Wombacher-Andrews learned that a good many women were, so to speak, her sisters under their skins. Some of them came buzzing into Hollywood, and decidedly got under her skin.

What, asked the newspapers, could Watson tell about Mrs. Alice Ludvigson, whom he married under the name of Lewis Hilton? Or Irene Root Gordon, of San Francisco? Or Bertha Goodnick, of Spokane? Or some fifteen or sixteen others, from Kate Pruse, of British Columbia, to Anna Merrill, of Massachusetts?

In short, the papers sang an unrhymed "Ballade of Lost Ladies." It had to be unrhymed: not even François Villon could have done much with a name like that of the wife from Vancouver—Myrtle Briggs Fritch.

There was also "the unidentified body found last summer in Martinez Canon;" an unnamed lady carried to the morgue in this town, or found floating in such and such a harbor. There was his room in a hotel at Santa Monica, taken under the name of "James Lawrence," and decked out with a lot of furs, a Paisley shawl worth $1500, and "a rich widow from Victoria who had a date to meet him on the beach."

Meanwhile, sang the editors of the Los Angeles papers, where was Margaret Myers Stokes of Portland, Oregon? And has anybody here seen Irene Erickson of the Alameda County Hospital? Where are the Four Ladies of Tacoma who were all married to him at the same time?

After keeping everybody in a perfect feeze for nineteen days, Mr. Watson made a Statement. It was sufficiently astounding to bring him back on the front page, with a seven-column head: BLUEBEARD WATSON CONFESSES. Many people thought he had really "come clean" at last—a thing which this grimy little fellow never did in his life.

Yet, uttered in his deprecatory manner, this partial confession was not without its points. He said he had married fifteen women, and murdered four of them. Later, he raised the number of marriages to eighteen and the murders to seven. He described six murders in detail. The names of two of the eighteen brides were, he said, unknown to him, and always had been. A later estimate—not made by Watson— raised the number of marriages to twentysix.

His method was as follows. Going to and fro in Canada and the United States, driving his little car up and down in them, he would frequently put a newspaper notice in the matrimonial columns:

PERSONAL: Would like to meet a lady of refinement and some social standing, who desires to meet middle-aged gentleman of culture. Object matrimony. Gentleman has nice bank account as well as a considerable roll of Government bonds.

H. L. Gordon,

Hotel Tacoma.

Such a notice would be promptly answered, say, by Mrs. Jennie Leighton, who would write a long letter, confessing to a previous marriage when she was only a child of fifteen. She would also admit 147 pounds, dark hair, pretty teeth, and a "starved soul."

Mr. Gordon-Watson would reply, opening his letter rather formally, to "Mrs. Jennie Leighton," but progressing rapidly in warmth of diction until, at the fifth line, he was calling her the "girl of my dreams." He would assert that, in addition to his bank-account and his roll of bonds, he had other advantages, including "certain personal traits which have been considered different from most of my sex." He was rather vague about them, fearing to be thought "conceited."

His form letter, of which he had dozens, all typed, added:

"I am in the thirties, have brown hair, blue eyes and fair complexion. Weigh 150. Am 5 ft. 7 in. tall. I believe in the better and elevating things in life." (Police records say that he rather underestimated his age, which was 42, and overstated his weight, which was 135.)

By this exchange of letters, it was easily settled, and Jennie Leighton (like a swarm of Irenes, Kathryns, Gertrudes, Ninas and Myrtles) would speedily become Mrs. Gordon (or Harvey or Huirt or Andrews or Watson).

Then they started cruising about in his car. He told some of his wives that he was in the secret service, and consequently had to travel all over the country on confidential missions.

Most of his wives had savings, or Liberty bonds, and these were promptly transferred to his care. He always combined business with pleasure, and his strict attention to the profits of the game (as with other men of his kind) discounted the earnest efforts of alienists to classify him as a person suffering from a "compulsion neurosis."

(Continued on page 68)

(Confirmed from page 45)

He had, in his bag, letters addressed to fourteen women in Canada and England, and scores of sheets of paper signed at the bottom with women's names. The latter were to be filled in by Mr. Watson with wills, or with letters to reassure the relatives of these women—after they were dead.

In his confession, he described how one of his wives fell out of a boat into a river; how his efforts to recover her failed, and how he thought it unwise to report the "accident." How Bertha Goodnick perished in a lake near Spokane; Alice Ludvigson in a lonely wood in Idaho; and Betty Prior near "Plum," in the state of Washington. As for Nina Lee Deloney, he drove her to the vicinity of Long Beach, California, killed her with a hammer, and buried her in the hills near El Centro.

It was to the burial place of Mrs. Deloney that Watson gladly guided the officers. In a sense, he had the law by the throat in California and, in return for his confession, had been able to wangle a promise of nothing worse than a prison sentence.

On his own confession, he was sentenced to life-imprisonment at San Quentin. It was recorded that he heard the sentence "with deepest gratitude." It was also recorded that his fellowprisoners, as he entered the yard, spat upon him. Perhaps they felt a sense of injustice when they remembered that so many others, who had been guilty of much less cruelty, had not been treated with any consideration at all.

After all the researches of the newspapers, Watson remains a mystery. Within a few days of his committal to prison, the papers ceased to call him Watson, and referred to him as "Joseph Gillam." He had been vague about his origin and early life; telling the truth when it might serve his interests, but lying most of the time. Even his vaunted confession began in this discouraging fashion:

Question: "What is your name?"

Answer: "I do not honestly know."

To the end, Mrs. WombacherAndrews (wife #23, according to some computations) continued the most fortunate of all. She accompanied #19, a Mrs. Elizabeth Williamson of Sacramento (who married Watson under the name of Harry Lewis) to Santa Monica—perhaps to run down the "rich widow from Victoria." Mr. Nick Harris, who sat between the ladies in the car, recorded their conversation. Said Mrs. Williamson-Lewis:

"I used to sit up at night and put up jelly, so he could take a jar or two in his grip, when he went on those trips."

Mrs. Wombacher-Andrews spoke:

"Dearie," she said, "was it currant jelly?"

"Yes," replied the other.

"Well," replied Mrs. WombacherAndrews, "he used to bring it all to my house, and we would eat it."

Then all three of them gazed sadly at the golden sun, sinking into the Pacific, behind the Santa Monica palms.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now