Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Theatre

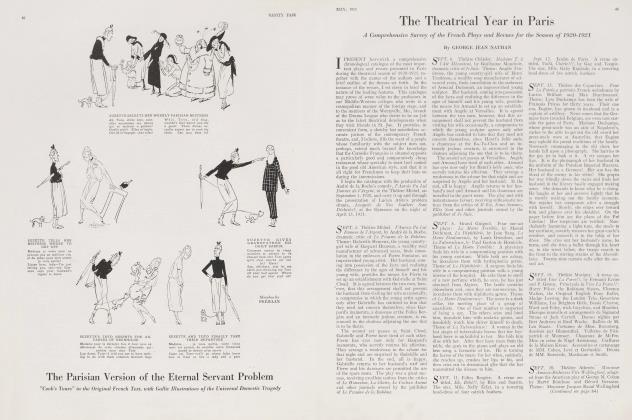

George Jean Nathan

THE PATIENT GROWS STRONGER.—That the local stage, for all its many still painful cramps, is slowly on the mend and promises an aesthetic health that was never in it before, becomes more and more cheerfully evident, even to such a scrupulous if somewhat exasperatingly pertinacious recorder of the aforesaid cramps as myself. Certainly a New York season that thus far has witnessed a hospitable run of more than one hundred performances for so new and difficult a play as Within the Gates, that has brought to the American drama The Children s Hour, and that has seen our first comedy writer come more fully to flower in Rain From Heaven is indicative of something. The first named exhibit would not have stood the shadow of a chance a relatively few years ago; the second would have been censored and doubtless suppressed; and the third would have received scant sympathy from even the critical chaperons of the drama's behavior.

Nor are these the only straws in the wind. In other directions, albeit on a lower plane, we also observe a determined and commendable striving toward a new and better order of things dramatic. The striving, true enough, is still often in vain, but at least its feet are gradually getting themselves out of the old squashy muck. As is usual in the case of one who has been down with an illness, however, our recuperating theatrical patient has believed itself well enough to go out and kick up its heels before the doctor has agreed, and the results of its premature excursion have been not too fortunate. We are thus currently entertained by a wholesale ambition with a retail talent boozily proclaiming the strength of its weak legs all over the place and by an invalid that mistakes its remaining fever flush for the glow of health. But, even so, a new dramatic integrity and prosperity seem to be just around the corner.

I have mentioned Behrman. Since the felicitously endowed and developing Vincent Lawrence was swallowed up by Hollywood, this Behrman has had no competitor here as a contriver of literate, intelligent and thoroughly adult comedy. There has been in him since first he began to write (I had the pleasure to be, I believe, the first editor to publish his early work) a complete and incorruptible probity and a regard only for himself—apart from all other considerations—as an artist. If he has ever thought of editorial checks or theatrical box-offices, it must have been in his sleep, and then only during the Prohibition period of bad liquor. Even his poorer work never fails of dignity. And year by year he suggests a growth visible in the instance of few of his American contemporaries. His latest play, this Rain From Heaven, a study of present-day ethics and prejudices in fierce open clash, is a testimonial to the fellow's fine honesty, very considerable skill in drawing character in short, sharp strokes, high gift for dialogue, and steadfast avoidance of every trace and smell of facile theatrical sham. If he happens to have a theme, as he has in this case, that may best be treated with an almost complete dramatic quiescence—that is, in the Philistine critical sense—well, that is the way he treats it, and to hell with anybody, in or out of criticism or the box-office, who doesn't like it. If he feels a thing, he lets himself feel it, let audiences in turn feel whichever way about it they will, and may they go hang. It isn't that he deliberately slaps popularity in the face; it is rather that he appears never to be conscious that such a thing as popularity exists in the world, or at least in his immediate world. He is a writer, whatever he writes (which is uncritical criticism), with whom our theatre, still replete with poslurers and charlatans, may be vastly satisfied.

There is one moment in Rain From Heaven that illustrates more nicely, I think, than any in the more recent dramaturgy the gulf that yawns between the new drama and the old drama of the Pineros whose influence, as Charles Morgan has lately pointed out, dominates still to no little degree the more backward and lesser Anglo-American stages. That moment comes at the curtain to the second act. The scene is Lady Wyngate's house outside of London, wherein— under her hospitable roof—is gathered a party of Americans and of German and Russian refugees. Suddenly jealous of the attention his Lady is privileging the German exile Willens, the young American hero spatters at the latter the sling, "You God damned Jew!", the which is immediately echoed by his elder brother. Willens, in the dead silence that follows, makes no move. Whereupon Lady Wyngate, taking his hand, in the quietest and smoothest of voices turns to the two others, still colored with bitter distaste and hate, and says, very softly, very graciously—and unexpectedly and jokingly enough in the case of the young suitor for her favor—"Remember, please, Mr. Willens is not only my lover; he is also my guest."

There never lived a Pinero, a Henry Arthur Jones, an Alfred Sutro or any other such exponent of the older drama who would not, to achieve a hokum surprise second act curtain, have turned that line hind end foremost!

(Continued on following page)

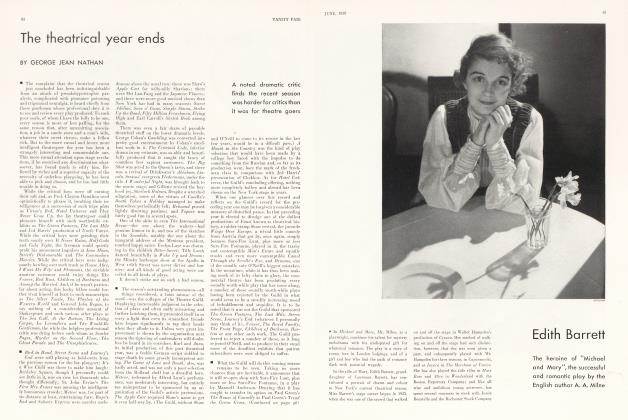

THE CORNELL JULIET.— In an effort to make her Juliet obediently youthful to the text and properly in key with the teensful Shakespearean spirit, Miss Katharine Cornell, that otherwise most charming and most valuable asset to our stage, leaned so far forward that the performance often took on the aspect of F. Scott Fitzgerald's debut as Little Eva with the Princeton Triangle Club. Such was Miss Cornell's unremitting insistence upon the externals of virginal girlhood and the theoretical deportmental concomitants thereof that of Shakespeare's Juliet there remained little more than an impression of Louisa M. Alcott's Jo.

Why is it, one wonders, that of all the youthful roles in the higher drama Juliet is the single one which in more recent years has induced in our mature actresses the idea that only by converting themselves into a behavioristic diaperdom can they effectively play it? The great Juliets of the theatre have not made that mistake. They have realized the complete absurdity of any attempt to play the role in terms of a sapling when their Romeos, nine times out of ten, are and must be played by actors obviously and emphatically in their late thirties and forties. The dramatic contrast, they have appreciated, becomes increasingly ridiculous as the visualization of Juliet goes lower in the age scale. What is more, these wiser actresses have understood that, if—like the fourth wall—a dramatist's stipulation of a heroine's age is taken by audiences more or less for granted, or at least with a politely remitted judgment, in the case of the realistic drama, it certainly may be accepted doubly in the poetic drama. If fortyfive-year-old actresses may easily pass muster as twenty-nine-year-old Hedda Gablers, if thirty-five-year-old actresses may convincingly play twenty-two-year-old Hilda Wangels, and if a forty-year-old actress could play the youngster Peg in Peg o' My Heart to the complete and wholesale intoxication of three years' paying audiences, there doesn't seem to be much critical sense in an actress of thirty-five or so (herself sufficiently lovely and attractive) who imagines that the best way to play Juliet is to make her a kid sister to Shirley Temple. What, one speculates, would Miss Cornell do with such a role as Hermia—"Thou hast by moonlight at her window sung," or such a one as Cordelia?

Another point. Assuming that what is indited above is deficient in sound critical sense, where still is the sound histrionic interpretive sense in imagining that a very young girl in love—or out of love, for that matter—comports herself, as did Miss Cornell, after the excited, jumpy, gurgly manner of a white Topsy? Is not such a conception in direct line with the old stock company idea and direction of ingenue roles? Where but in tender youth does one find, even under poetic stress, a natural, artless, and often very confounding and embarrassing poise, and dignity, and skeptical reserve?

SHERWOOD FOREST.—Ever since the late William Archer wrote himself into the public awe and a considerable slice of the box-office with a 10-20-30 melodrama that contained one two-dollar allusion to Bernard Shaw, writers of melodrama on both sides of the Atlantic have tried to horn in on the technique of The Green Goddess' author. The result has been a succession of melodramas in which the old-time smell of gun-powder has been largely supplanted by the smell of the book-shop and which, in many cases, are distinguishable from drawing-room drama only by virtue of the fact that certain of their scenes are laid out of doors.

The latest follower in what are at least Archer's technical footsteps is Mr. Robert E. Sherwood. His exhibit is called The Petrified Forest and it improves upon Archer's single reference to Shaw with three references to Mark Twain, Lew Wallace and François Villon. This, naturally, has created a tremendous stir among my friends, the critics, one of whom, "Handsome John" Anderson, has been so enormously impressed that he has hailed the exhibit as "wise, mature, of rich flavor and fine penetration . . . there is more in it than meets the casual eye or the midnight typewriter . . . here is a play to take and hold high . . . my hat is off ... and if I had four hats they would all be off in general and grateful salute." Such enthusiasm is easy to understand when one recalls that not only has Mr. Sherwood mentioned three authors but, improving even more greatly upon Archer, has included in his melodrama three machine guns. This combination of intelligence with the most vigorous boom-boom props of old-time blood and thunder melodrama has been irresistible. The show is a huge success.

Nor has Mr. Sherwood stinted in other directions. As the critics will rapturously tell you, he has further embellished his exhibit with "some remarkably fine and profound symbolism", the aforesaid remarkably fine and profound symbolism reposing in the title of his play of which "for clue Mr. Sherwood makes the artist say that he belongs in the petrified forest with all the other dead and turned to stone illusions of a credulous society."

Then there is, too, "some deep philosophy." It is somewhat difficult to make out from the ebullient critical appraisals just what and where this deep philosophy is, but from a first-hand engagement with it I take it that an illustration may be had in Mr. Sherwood's hero's proclamation that Mr. Sherwood's heroine is just what the present world needs for its salvation, confidence and faith.

This heroine is a young girl working in a lunch room at a crossroads in the eastern Arizona desert,. Gabby Maple by name. Gabby is a free, outspoken sweet one who offers herself without marriage to the hero and offers, to boot, to provide him with money out of her own pocket. When he declines the proffer, she promptly tenders herself for a moonlit roll in the grass to a husky young employee of her father's. In a word, Gabby is, one fears, what is known in unrefined society as a pushover. This particular phase of Mr. Sherwood's "deep philosophy" as to what the present world needs for its salvation, confidence and faith therefore seems to elude me. Nor am I able, fathead that I am, to get much farther into his metaphysic arguing that "the artist and the gangster, the dilletante and the bully, are useless and impotent and archaic, but that out of them and this present confusion may come a world that is fit to live in." How the world is going to be improved by getting rid of artists and gunmen and substituting for them pushovers with a penchant for the ejaculation bastard, I am afraid I shall have to leave to younger philosophers than myself to figure out.

(Additional reviews of the theatre by Mr. Nathan will be found on page 72.)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now