Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Hanging of Hicks the Pirate

The Last of His Spectacular Profession Perishes on the Gallows in New York Harbour

EDMUND PEARSON

IN March, a few months before Abraham Lincoln was first nominated for the Presidency, New York newspapers were much excited about a tragedy on the "high seas." The seas were really no higher than those to be found in the lower harbour, and the ship concerned was a humble sloop, with the unimaginative name of E. A. Johnson. She belonged in Islip, Long Island, and under command of a mariner named Captain Burr, was in the habit of bunting oysters in Virginian waters, and bringing them back to the New York market. She had sailed on one of her oyster-catching voyages, manned by the Captain, and three sailors,—a mysterious person called William Johnson, and two blameless boys, Smith Watts and Oliver Watts, brothers. She progressed no further than the Homer Shoals, and there was picked up and boarded by the schooner Telegraph of New London.

All was not happy on board the E. A. Johnson. For one thing, she bad been in a collision, and had her bowsprit carried away. Next, she was quite deserted: neither Captain Burr, nor the Watts boys, nor Sailor Johnson was visible. A tug brought the sloop up to Fulton Market slip, and the reporters for the New York newspapers came down to look at her. These young men, all wearing tall hats and chin beards in the correct and sporting manner of the day, found on the deck and in the cabin of the E. A. Johnson what they agreed in calling "unmistakable evidences of foul play."

There was blood all over the ship; pools of blood in some places; in others, stains, where an effort had been made to wash away the unpleasant signs of murder. There were two or three stray locks of hair. Furniture was upset in the cabin, and there were found coats and shirts, cut and gashed in the struggle. These were not proper to an honest oyster-man, and the police began to bunt for her crew.

IT appeared that another schooner had been in collision with the oyster-ship, early that morning, off Staten Island, and that the crew had seen one man leave the E. A. Johnson in a boat. Two kind gentlemen, named Burke and Kelly, who lived in a "low tenement house" on Cedar Street, told the police that Sailor Johnson lived in the same house, and that, moreover, the sailor had returned unexpectedly with an unusual amount of money. He had won this, so he said, as prize money for picking up a sloop in the lower bay. Messrs. Kelly and Burke added that that their friend had then departed for Providence, R. I., via the Fall River steamer, taking his wife and child with him. Further interesting information came from the keeper of an eating house at the Vanderbilt landing. He had seen someone like Johnson, who had "made himself conspicuous",—in what way, I do not know, but probably by his choice of refreshment, since he had "indulged freely in oysters, hot gins, and eggs." One would have thought that the oyster would have been a fish accursed in his sight, but it was not so.

Two police officers went to Providence in pursuit of the sailor. They had mild adventures for a day or two, but at last, by means of what the newspapers used to call clever detective work, spotted their prey. Some young man, who wishes to become a detective, may read this, so I will explain how this clever detective work is carried on. It consists of going to a great number of persons, one after another, and asking them:

"Say, have you seen a feller who looks thus an' so around here, anywhere?"

The officers found Sailor Johnson asleep in a lodging house, and arrested him. His name was not Johnson at all, it was Albert W. Hicks, hut whether he told them that, or whether Mrs. Hicks gave it away, I have been unable to discover. He bad with him about $120. in bills; Captain Burr's watch, and some other property, the possession of which tended to create rather an unfavourable impression in the minds of the police. This prejudice influenced the citizens of New London, as well, for when the prisoner passed through that city on his way back to New York, the New Londoners (all wearing tall hats) made a rush for the railroad train, and insisted on the privilege of lynching Mr. Hicks. The two officers (in ulsters and tall hats) their left hands raised in deprecatory gesture, and their right hands holding small revolvers, waved away the citizenry, and landed their captive safely in a New York jail.

Here he was presently visited by his wife, who held his child up in front of the cell, and addressed the prisoner in the following remarkable language:

"Look at your offspring, you rascal, and think what you have brought on us. If I could get in at you I would pull your bloody heart out."

Her husband replied with dignity and calm:

"Why, my dear wife, I've done nothing,— it will be all right in a day or two."

He continued his cold indifference during the five days of his trial, which took place in May. Although he had been indicted for the murders of Captain Burr and the two boys, he was tried on the indictment for piracy. Murder, at sea or ashore, is equally objectionable to the law, but Hicks made the grievous mistake of committing robbery "upon the high seas, or in any basin or bay within the admiralty maritime jurisdiction of the United States." This, Congress had said in 1820, was piracy, and punishable with death. I am sadly aware that Hicks' portrait does not satisfy our fancies of a pirate, but the law treated him with as much careful ceremony as could have been afforded to Blackboard himself. Moreover, the money which he pilfered from the Captain, was really in gold and silver,— in that respect the story is not altogether prosaic. Hicks had changed it into bills before leaving New York.

DURING the trial there appeared Cathorine Dickinson, the seventeen year old sweetheart of Young Oliver Watts. She testified that the lock of hair found on the sloop came from her lover's head; and that a daguerreotype, found in Hicks' possession, was a portrait of herself, which she had given to Oliver. While the taking-off of Hicks was grotesque, hideous, and unpleasantly public, I am willing to leave to others the task of weeping for him.

After his conviction (it took the jury but seven minutes of deliberation) Hicks made one of the most elaborate and highly ornamented confessions ever attributed to a native of Foster, Rhode Island. In it, he gave himself the worst of characters; acknowledged an unholy itch for wealth and complete absence of good taste in his methods of getting it. Very early in his life, he stumbled into evil ways in Norwich, Connecticut. A few years later, by a roundabout route—'round the Horn—be reached "Wahoo" in the Sandwich Islands. Here he deserted specialization, and embarked on sin in general. He says briefly, "I engaged in every kind of wickedness." Robbery, mutiny and murder—so he asserted—became as much a part of bis daily programme as coffee, tea and grog.

He transferred his attentions to Lower California; "dyed his hands in human blood" lie knew not how often; and made himself thoroughly objectionable.

"The old man," he writes, "whose grey hairs glistened in the moonlight, and whose venerable presence might have touched any hearts but ours; the little children, locked in each other's arms, dreaming of butterflies and flowers and singing birds; the young man and the just budding woman; the fond wife and the doting husband, all fell beneath my murderous hand; or were made the shrieking victims of my unholy passion first, and then slaughtered like cattle."

(Continued on page 116)

(Continued from page 55)

And so on ad infinitum. He ranged up and down North and South America and Europe, like Hack Finn, the Red Handed, and Torn Sawyer, the Black Avenger of the Spanish Main,—both of whom, I suspect, were then working for some New York newspaper. Finally, in his confessions Hicks described the undoubted crimes on the oyster-sloop. His plans for burning her, after the murders, went to pieces when she collided with the other vessel, and he was terrified into making his escape in the small boat. He landed first at Staten Island; and then returned to New York, and his breakfast.

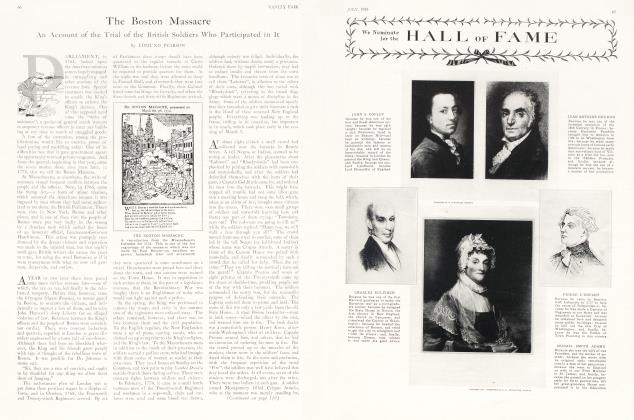

Friday, July 13th, 1860, was the day appointed for the hanging of Hicks, the Pirate. The place was Bedloe's Island, now Liberty Island. It is not probable that any pirate has had the sentence of death executed upon him in New York Harbour since that date. —certainly not in the presence of such a "vast concourse". As the vast concourse included ten thousand persons, some of them must he living today. Many a respectable citizen slipped away from home that morning, and came hack at night expressing disgust that so many people had such morbid curiosity, but silent as to his presence on the island or on the waters nearby. To us of today, such a curiosity is horrible, hut in 1860 a hanging was no worse spectacle to the average citizen than a prize-fight is in 1927.

Hicks received the consolations of religion from Father Duranquet, and afterwards partook of a cup of tea and "some slight refreshments." Then he proceeded to array himself in his hanging costume, which was remarkable as an example of what the well-dressed pirate wore in 1860. It was "a suit of blue cottonade, got up for the occasion. His coat was rather fancy, being ornamented with two rows of gilt navy buttons, and a couple of anchors in needlework. A white shirt, a pair of blue pants, a pair of light pumps, and the old Kossuth hat he wore when arrested, was his attire."

A procession of four carriages left the Tombs before nine o'clock in the morning. The prisoner was in the first carriage, with the priest, the marshal, and two assistants. At the foot of Canal Street they all boarded the steamboat Red Jacket. The scene there, as all the reporters agreed, "baffled description." There were 1500 persons on board.

The famous steamship Great Eastern was in the river at this time, lying of! Hammond (now West Eleventh) Street. As many of the passengers in the Red Jacket wished to see the great ship. Marshal Rvnders approached Hicks, and asked if it would he an inconvenience to have the hanging postponed for an hour or two. The prisoner expressed himself as quite at the disposal of the gentlemen on the Red Jacket and added that no number of postponements would annoy him in the slightest degree. So the steamboat made a turn up the river and gratified the curiosity of the passengers. Then the Red Jacket was put about for Bedloe's Island.

Following the example of Thackeray at the execution of Courvoisier, we will turn away from the gallows, and look at the harbour. Steamboats, barges, oyster sloops, yachts and rowboats covered the water within view of the scaffold. They had come from many places, hut especially from Connecticut and from Long Island, where the brothers Watts were known. There were barges with awnings spread, under which thirsty passengers drank lager beer. There were row-boats, with ladies,—no, says a shocked reporter, with "females of some sort" in them. They gazed from under the fringes of their parasols, as the final penalty was exacted. Newly painted, and anchored within three hundred feet of the gallows, was the sloop E. A. Johnson, on which the murders were committed. A huge burgee, with her name in red letters, flew up from her topmast. Her deck was crowded, her masts and spars covered with sight-seers. She was the most conspicuous sight to the eyes of the dying man.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now