Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOn Conversing With Authors

Some Advice to Those Who Find Themselves Frequently in the Company of Literary People

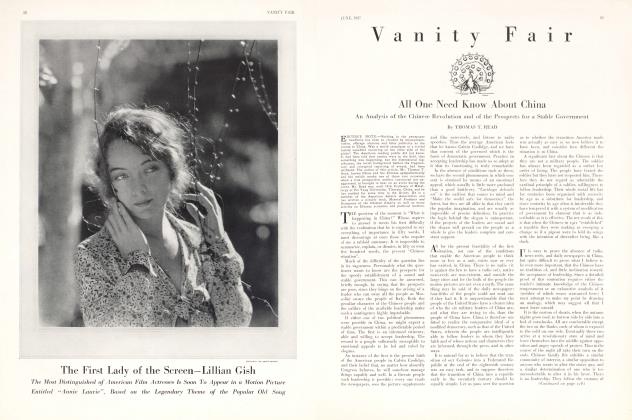

SHERWOOD ANDERSON

FOR a long time now I have been thinking that something should he written giving some rather formal rules for conversations between authors and common people. As the matter stands both authors and people suffer a good deal through lack of understanding of each other. There are, I am told, some thirty thousand clubs in America that hire authors to come and lecture to them. Authors go to these places when in need of funds and must be met at trains and, as you can see for yourself, the field is pretty rich. Even at a dollar a club thirty thousand clubs should bring in thirty thousand dollars—a lot of money to an author. I myself have a plan I would like to propose to a few of these clubs. I will lecture in any town on the following understanding, that is to say, twenty-five cents to hear me lecture—a dollar for the privilege of not hearing me.

But we were speaking of the matter of conversations. Authors, as everyone knows, naturally pine for solitude but they do go about a good deal. I was in Kalamazoo, Michigan one day last week and met ten in the hotel lobby during the afternoon. Authors are becoming so large a part of our population that we should all try to understand them better. On shipboard they usually manage to conceal themselves in some obscure place, say at the captain's table, but ashore they are more in evidence.

They are, of course, very sensitive people. I, myself, have noticed that—when I have lectured somewhere—people, after the lecture, realizing my sensitive nature, are very reluctant about giving me money. As I stay on and on they grow more reluctant. When the matter becomes pressing they do not walk up boldly and give me the money hut put it in an envelope. They act as though I were a preacher and had just married someone—or had done something else of which I was ashamed.

It is because they think I am sensitive on the subject of money—and, of course, I am.

BUT, as I just said, an author, pining for solitude in a strange town, at once goes and tells someone he is there and that he is an author. "I am the man who wrote Buckets of Blood", he says to the taxi driver who takes him to the hotel. "Do not let anyone know. I am very sensitive and love solitude ". He says something of the same sort to the hotel clerk.

At once people, feeling how deeply he loves solitude, come to see him. There is need of a technique. Even among ourselves we authors hardly ever know what to say to each other.

In the first place I think it would he better if the subject of money were not mentioned. Those of us who make very little money are sensitive on the subject and those who make a good deal are ashamed. The subject had better be left alone. The main thing to bear in mind is our extreme sensitivity.

Also, if he happens to he an American author, I would not ask him who he thinks is the greatest American author. That is also a subject that causes extreme embarrassment. How many times I myself have been asked that question and how it does upset me. I swallow hard, grow a little red in the face and do not know what to say. Some time ago an editor had the bright idea of having an American poet pick, each month, the man or woman he thought had written the best poem. I was in Chicago at the time and I remember that Mr. Carl Sandburg, when it came his turn, picked a man whose poem had appeared in a newspaper in a small town, of interior Arkansas if I remember correctly. No one could get the paper to read. I thought it very clever of Mr. Sandburg. Since that time I work something of the same kind when people ask me about short-story writers or novelists.

Authors are very, very sensitive. You would never believe how sensitive they are. They may not be quite as sensitive as actors but they run them a close second.

In general it is a bad thing to speak at any great length of an author's work unless you have read a little of it. He will almost always catch you. Critics often do it very well hut they have had a lot of experience. If you haven't much time quotations may usually he had out of newspapers. In passing an opinion do not use the critic's exact words. Give them a turn of your own.

THERE is one thing you may always do with safety. This may be worked successfully, even if you have never read a word your author has written. First of all suggest that the mind of the author is too deep for you. Say something like this—"your mind is too deep for me but I always carry away with me a feeling of power, beauty. It is because your sentences are filled with haunting beauty. You do write such beautiful sentences."

If you will but say something like that I am sure it will he enough. Bear in mind that no author ever thought himself capable of writing a bad sentence. If you want to win his entire gratitude, not to say fervent devotion, and have an opportunity to look into one of his books you might commit one sentence to memory. The happiness you will bring to your author will repay you for trouble. It does not matter what sentence you choose. Choose any sentence. Surely, that will not he very much trouble.

I am only making a point of this because authors are becoming so large a part of our population. We might get into another war. We need to stand together. We should constantly be saying to ourselves—"see America first".

But I was speaking of conversations. Or was I telling you how sensitive authors are? They are really very very sensitive people.

In going into a room where there are several authors do not try to please them all. It would be better to pick out one author and devote yourself to him—or her. The others may be left for another time. If you try to speak kindly to two authors on the same occasion and they catch you at it you will only cause hard feelings. If you can praise the one author at the expense of another you will bring home to him, in the most forceful way, the fact of your own discernment. That is because he is so sensitive. For all you know he may make you the hero of his next book.

It is very nice to ask an author whether or not he takes his characters out of real life. He enjoys that.

It is very unfortunate to approach an author and say to him that you cannot get his books out of the library, that they are always out. This brings home to him the matter of money, it touches that is to say upon the question of his income. But it has been agreed that the money question is to be altogether avoided.

IF I had more time I would say something about the sensitivity of authors but you may have noticed that yourself. O, the sensitivity of authors—particularly in the matter of money.

Authors in general do a great deal of swearing under their breaths. That is other people's fault. It is because they are compelled by circumstances to associate so much with people not so sensitive as themselves.

When it comes to the morals of authors Well, after all, this is a matter that, like money, had perhaps better be left alone. It is a delicate subject. It is so easy to make a mistake. Too many people are likely to go up to an author and suggest that, although many other authors may he immoral they are sure he is not, that he is, in fact, a good man. Something of that sort, carelessly said, may make an author unhappy for months.

I have seen old friendships destroyed by such carelessness as that. An author I knew very well committed suicide after hearing something like that. Whatever you do never question the immorality of your author.

Do not go to an author and tell him that you are too busy to read very much. When you decide to quit drinking you do not call up your bootlegger to give him the glad news. But this brings up again the question of income and we had already decided to let that subject alone.

IT is always very nice, when you are in the midst of a conversation with an author, to suggest to him that his work reminds you strongly of the work of some other man. It makes him very happy. Say to him that, when you read his books, you always begin thinking of Mr. George Moore. Then tell him how much you admire Mr. Moore. Watch the glad sweet light come into his eyes.

By all means, when you are where authors have congregated, do not speak of anything but books. To speak of the weather, things to eat, horse races or any other topic other than authors and their work is very rude. Who wants to be rude to an author? It is the one thing we are all trying to avoid.

You are in a room with an author and there he is. Look how handsome he is. As likely as not, if you speak of ordinary things, you will disturb his thoughts. He is sure to he thinking. You may he quite certain that, as you go about your ordinary affairs, he has been consorting with the gods. When you have been in bed and sleeping he has been among the stars. Authors hardly ever sleep.

(Continued on page 98)

(Continued from page 40)

The main thing to bear in mind in carrying on conversations with authors is that they are no ordinary beings and do not think ordinary thoughts. If your author is a good author, and I take it for granted you would not associate with him at all if he were not great, the whole purpose of his life is to live quite separated from ordinary people.

He loves the heights and, therefore, wants to be constantly thinking of books. 0, how he loves conversing of books, thinking of books. And how, in particular, he loved thinking of and conversing of other men's books. Do not ever let this thought go out of your mind.

Authors really want so little and there are so many of them. They are very very humble and as J suggested, but a moment ago, O, how sensitive they are. All we need to do to get along better with them is to be a little more thoughtful. I am quite sure that, on account of the growing number of our magazines and the eagerness for intellectual stimulation, so characteristic of Americans in general, the race of authors will grow. That is why the subject is so important. For a long time I myself had the notion that like the negro race the race of authors would tend to breed out. that they would in short become whiter, but I am losing hope of that.

Authors become thicker and thicker. Hardly anyone can tell when he may be put into the position of having to hold a conversation with one of them. We should all try to learn how to do it. I have tried to make some suggestions that may be of help. Perhaps you can think up some for yourself.

The main thing is to be prepared. As I have said we Americans should stand closer together. Perhaps someone will shortly write a book on this subject. I hope they will. We need more books. That is one of the crying needs of our life.

Some lecture manager or someone who has worked a good deal in a publishing office or has had a good deal of experience at an editor's desk might by a little effort do something on this subject that would be really good. When the crossword puzzle craze and the "ask me another" thing has worn itself out a book might be compiled telling how to converse with each particular author.

We might begin with visiting authors.

However I dare say it would take too many volumes. It would cost too much. There I go—speaking of money again. You can readily see that 1. who am an author myself, do not know how to handle this matter.

Really I would suggest letting authors alone but that 1 am very fond of some of them. 1 do not want to see them commit suicide. And then besides we are in such crying need of books.

Something will have to be done. Someone with more keenness will have to teach us all how to converse and live with our authors.

Segregation might be a way out of the problem.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now