Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Man at the Filling Station

A Significant Moment in the Life of an Insignificant Home on the Wastelands Outside Chicago

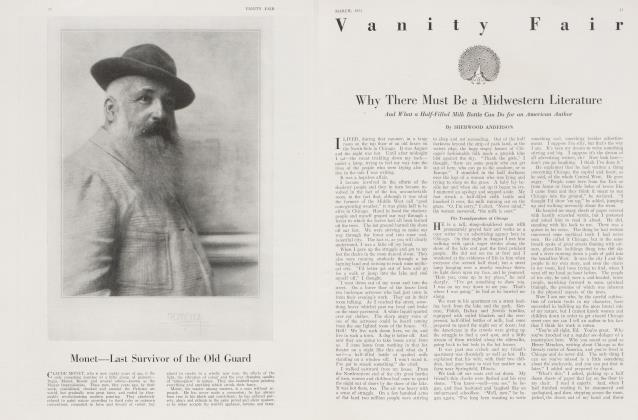

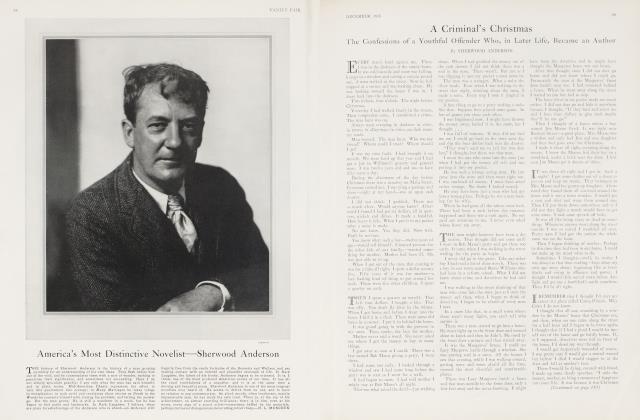

SHERWOOD ANDERSON

AN odd place for him to be living. It was two or three miles out beyond the edge of one of the factory towns that are sprinkled over the flat prairies which cluster about Chicago.

So many railroads come into Chicago. They come from the East, the West and the South, around the end of the lake and across the flat places. In the evening when you walk across that flat country you see trains constantly coming and going, far away. On a summer evening the sun goes down red and hot over the edge of the floor.

In the winter it is desperately cold out there and on summer evenings the sunset is never quite clear. There is always smoke hanging in the air in the distance.

There is a factory building out on a flat low place, with swamps all about. No other building for a half mile. Then another mile of vacancy and you come to Bill's place.

Crowds of labouring men come out of the factory in the evening. They huddle together by a street car track. The street car seems to come from some far distant place like Africa or Asia. What I mean is that it seems to come as from across a long flat sea.

It is a sea of green swampy land with occasional yellow stretches of sand.

THEY have built cement highways through the swamps and across the flat low places. Motor cars filled with men, women and children come out of Chicago, and out of the terrible factory and mill towns about Chicago, and run across the flat land.

They are going East and West and South. At night there is a flare of light against the sky from the steel mills at South Chicago perhaps.

A flare of lights against the sky and the sense of a great city, somewhere near at hand. The darkness of the long lonely stretches seems full of shadowy people sometimes.

You get to thinking of Chicago. People are always passing through there going east or west, north or south. It is a place of hundreds of thousands of unknown insignificant people. All great cities must be like that.

Bill was one.

I knew this man named Bill who had a gasoline filling station out there along one of the roads.

He sold gas and oil.

Then prohibition came. He did a bit of whiskey and beer selling.

I had got me a car and used to go out that way—to see the sun go down—to see the trains moving in the distance.

Back of Chicago the open fields—were you ever there? Trains coming toward you out of the West—streaks of light on the long grey plains.

If you go farther South or East or West the cornfields begin—huge long rich fields of corn. I used to get thoroughly sick of Chicago and drive at night until I could see the cornfields in the moonlight beside the road. Then I felt more at home.

On a farm at least a man is connected with something. He is connected with his piece of land. He has plowed there, cultivated, put seed in the ground, harvested.

There is his house and his barn, near the road, where the cornfields begin.

The house is white and the barn red. There are fruit trees near the house—a pig in a pen nearby.

You feel the man in the house, a little permanent, a part of something.

Bill had his red and white gasoline filling station, that was spick and span, and back of it hanging over the swamp was a little house, not so spick and span.

THE foundations of the house were stuck down into the soft mud. There was no place for Bill's children to play but in the cement road in front.

Bill was a large, loose-jointed man with dark, romantic eyes, a tiny brown moustache and a loosely-knit strong body.

By the front door of his house back of the filling station and attached to the wall of his house was a glass show case.

It was such a show case as you see in small town stores.

While I was having my car filled one evening I went to look into the show case.

A Confederate ten dollar bill, a mummified mouse, a butterfly pinned to a card.

Some bullets from the World War, a Masonic button, a woman's cheap breast pin, a German picture postcard.

More of such junk. Heaps of it.

There were men standing about. They looked at me with suspicious eyes. Perhaps they were the customers who consumed Bill's bootleg whiskey and beer.

Bill's wife was surprisingly young and handsome. She looked like a gipsy. Often I used to see her sitting on the doorstep of her house, her legs spread wide apart, her hands on her hips.

Her children cried and fought in the road in front of the filling station. She paid no attention to them. She seemed to be staring into the West, to where the sun was just starting to go down.

Bill did that himself sometimes. Gradually I got acquainted with him.

ONE night I came to the filling station quite late. It had begun to rain and I had been running my car slowly for miles along the flat road. There was a light in Bill's house back of the filling station. The filling station itself was dark.

I stopped my car. Bill and his wife were having a fight. Just as I came up he struck her a blow. He knocked her down.

When he did that he came out in the road to me. "Well?" he said. Then he looked into the car and saw who it was. His wife was lying on the floor in the front room of his house. He had knocked her down there.

She got up and came and sat in the open doorway with the light at her back. She put her hands on her hips and spread her legs apart.

"Come, get out," Bill said to me. I pulled the car to the side of the road. I was in a mood and so was Bill. God knows, I may have been in love just at that time.

My notion of this adventure is mixed up in my mind with some idea of unrequited love.

A kind of aching hunger inside that sends you driving a car across flat places at night. And nothing for the hunger to feed on.

"Let's take a walk," Bill said.

We walked for miles straight across the flat land along a smooth flat road. The wind blew and it rained little spatters of rain. It may have been twelve o'clock at night when we got started.

Then Bill began telling me of his adventures. There was nothing very exciting. As a young man he had been to Mexico, he said. He said he had been a cow man in Mexico and in the Panhandle of Texas.

He spoke of Mexican women. "They are all right and easy to get," he said. We walked on in silence for a time after he said that. "God," he cried suddenly. The word came with a little explosive bang from between his lips.

Then he spoke of helping to build a railroad somewhere in Southwestern Missouri.

We just went along like that and Bill talked. When we came back from our walk out of the darkness and the rain, I pointed to the show case by the front door. "What's that stuff you have in there?" I asked. "Oh, it's just stuff. It's junk. I just picked it up. Everything's junk," he said.

HE said he wanted to show me some snapshots he had had taken of himself when he was out West. He had scores of them. There were snapshots of Bill in Mexico, one, I remember, of him drunk—two Mexican women clinging to his arms.

There was one of Bill and an Indian woman standing together by a farm-house door. There were pictures of Bill on horseback, in cowboy togs—Bill leading a horse by a halter—Bill astride a horse driving cattle.

Bill standing on top of a mountain with his hat in his hand, the wind blowing through his hair. While we looked at the snapshots Bill's wife stood silently back of us looking over our shoulders.

I prepared to leave. Bill followed me to my car.

"Where did you get this woman?" I asked. "Oh, in one of the factory towns out here," he said, pointing.

"I am having my kids by her," he said. That seemed to Bill to explain Bill and so I drove away.

When I drove away, at perhaps two o'clock in the morning, Bill's wife was sitting on the doorstep of her house with the light shining over her shoulders. Her hands were on her hips and her legs were spread apart.

They may both have been waiting up—say, for a truck to come and bring them a new lot of their bootlegger's supplies.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now