Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Nowcountry squires

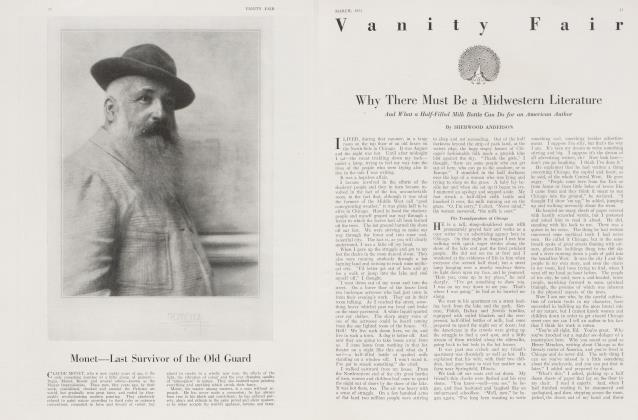

SHERWOOD ANDERSON

concerning the everpresent prototype of a class that has supposedly disappeared

There are thousands of them. In some states they are called "justices of the peace," in others "squires." Theirs are the little neighbourhood courts in which are tried the chicken stealers, the small damage suits—as when a farmer's horse gets into another's corn—the assault cases, some of the liquor cases, petty thefts of all sorts. When I was a boy we had a Squire as a neighbour. He had a tremendous voice.

The man was an early riser and in the summer was abroad at five. He stood on his front porch. Seeing a neighbour three or four blocks away, he began a conversation. His voice rang through the little town and honest citizens, awaking, cursed the Squire.

Still the man was liked. He laughed with his whole body. His fat belly shook and he waved his arms. He had a trick he could do with the muscles of his belly. He drew the belly in and then let it fly out. Grasping a small boy he embraced him enthusiastically. The belly was drawn in, taking the boy with it, and then it was let fly. The breath was knocked out of the boy. He fell to the ground and the Squire stood over him, roaring with laughter. All the by-standers laughed too. Such a man could be elected Squire over and over. No one could beat him.

There was another one who was a shoemaker and had lost a leg in the Civil War. He leaned toward the socialistic theory of government and, as he pegged shoes, he quoted Karl Marx. The men of the town went to his shop on winter afternoons. He leaned forward and punched at the floor with his shoe-maker's awl. "The capitalists are bringing the country to ruin," he declared, the blue veins standing out on his forehead.

The Squires are nearly all small farmers. In Virginia, where I now live, three Squires rule over each squirarchial district. The size of the district is fixed quite arbitrarily. In our county we have three such districts and therefore nine squires, while in the next county, but slightly larger, there are seven districts and twenty-one Squires.

The Squire receives no salary but is paid one dollar for issuing a warrant and two dollars for trying a case. When the prisoner is found guilty he must pay the costs, the Squire's fee, the fee to the officers who serve the warrants, and the witness fees. Witnesses receive fifty cents for coming in and testifying and, when they must come more than five miles, a certain sum, per mile, for the cost of getting there. If the prisoner is found not guilty the cost is paid by the state.

The court of the Squire is held in the winter in a farmhouse living room and in the summer on his front porch. In most farmhouses there is a bed in the living room. The Squire's wife is working in the kitchen. You can hear the rattle of pans. When the case interests her, as for example when the fatherhood of an illegitimate child is to be determined, or when there is some other misdemeanor that comes directly into the world of woman, she comes in her kitchen apron, and stands by the door listening.

There is always a crowd present. The men and women have come from all the neighbouring farms. In the summer, children are playing on the lawn before the house and the women have fixed themselves up. They sit stiffly on chairs brought from the house, in their stiff clean calico dresses, and whisper to each other.

The Squire's court is the theatre of the countryside. Here the tragedies and comedies of the neighbourhood are played out to an appreciative audience. For the smaller cases there is rarely a lawyer present. The country people are suspicious of lawyers. They are a necessary evil at times but it is best, when possible, to go on without one.

And the Squires are also happier when there are no lawyers present. A lawyer is always telling you how to do things. He has ideas about the procedure of a court. He brings law books with him. "In such and such a case, State of Vermont, volume so and so, page so and so . . ."

"Eh!"

"The devil! What have we to do with Vermont?"

In a Squire's court the man or woman being tried is personally known to the Squire. "Well, Jim—or Lizzy, what about it, eh? Do you agree to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth?" Often several people are talking at once. Lizzy has had a fight with Martha Smith. On Sunday evening Martha went to church and got to flirting with Lizzy's husband. Lizzy saw her talking to him in the road. Then on the next day Lizzy and Martha met in the same road. There were words and a fight started. Lizzy got a black eye and Martha had her face scratched. It was Martha who took Lizzy with a warrant. "I wasn't doing a thing. I ain't that kind of a woman," Martha says.

She begins to testify, and in the midst of her testimony makes a statement that seems to Lizzy an untruth. "You lie," screams Lizzy from her place on the Squire's front porch. Both Lizzy and Martha have to be held back by their friends or they would go at it again, right in the Squire's court. The man about whom all this fuss is being made sits sheepishly under a tree. The other men are laughing at him. He is filled with resentment. His wife should have gone on home about her business. He and the woman Martha weren't up to anything. Now the men of the neighbourhood are whispering together and laughing. His wife has got him into a hell of a mess.

The Squire may not pass on a case involving a felony, where there is a prison term hanging over the accused. He may, however, ask questions, find out if there is enough evidence to justify the man's being sent to court or to the next meeting of the grand jury. Most of the liquor cases have become felonies now. These stiff penalties they are putting on for violations of the liquor laws, are cutting down the number of cases that properly belong in the Squire's court. It cuts his income too.

In the court of Squire McHugh, who is an old man of eighty-two, the case of Jim McGrew is being heard. Jim is a thin-lipped, smiling man of forty-five, who has a slight limp. His case has attracted wide attention, and neighbours have come to court from all the cornfields around.

It is such an unusual case, that the sheriff, who took Jim and his two sons, Harold and Burt McGrew, has come over from the county seat, and the county Prosecuting Attorney has come.

It is obvious that these two men are bent on convicting Jim and his sons, who are accused of chicken stealing.

But Jim is slick, with a hard good-natured slickness difficult to get past.

There have been chickens missing from the neighbourhood for months. It isn't a question of a few chickens. Mrs. Sullivan, a widow, lost forty-two fine hens in one night, and John Williams, a prosperous farmer, lost thirty.

The hen-houses were safely locked at night and there was no noise, not a sound. On the night when Mrs. Sullivan's hens disappeared she was lying awake. She did not sleep a wink all that night. She remembers having locked the door to the hen-house. They were just gone. Not a sound from the hen-house.

In these days, when almost anyone can own a cheap car, a carload of chickens may be lifted in one neighbourhood at night and be a hundred miles away by daylight. A man who looks like a farmer, drives up to a dealer in poultry in some distant place. He sells the chickens, gets the money and leaves. The hens are shipped off to a distant market. How are you going to identify chickens after they get into the dealer's shipping crates?

The man named Jim McGrew lives in a little house on the side of a hill and has six children. They are all in court, with Jim's wife, and look like a brood of young foxes. All of them have sharp eyes, like Jim's, and you can get nothing out of them. The "whole neighbourhood knows that Jim never works. He lives in one neighbourhood until it gets too hot for him and then moves to another. Wherever he goes things just disappear.

Continued on page 128

Continued, from page 63

He's slick. In spite of themselves, the Squire and the neighbouring farmers, who have gathered in, admire his smartness.

They might have got him one time —there was a hen-house, filled with fine friers, back of the rich man's house—but for Jim's brood of kids. When Jim operated he could scatter kids all over a neighbourhood. People said they had a system of signals. A dog barked or there was the mew of a cat. Then Jim got out into the road and came moping along, as innocent looking as you please.

He likes to smile at the Sheriff, with that cold smile of his.

"What are you doing here, Jim?"

"Well Sheriff, if you want to know the truth, I came out here to get some whiskey. A man was going to sell me some. I guess he saw you here and he lit out."

Whiskey indeed. Jim was after them friers.

The Prosecuting Attorney is after something now. He scents a liquor case. "Where does he live?" "I don't know." That smile is playing about Jim's lips.

The Prosecuting Attorney is asking him to describe the fictitious man who was to sell the liquor.

"Well," Jim drawls, "he had two gold teeth, like you got, and had grey hair, like the Squire there." He points out the more respectable men present. The fictitious whiskey seller had eyes like this one, wore a hat like that man over there, had on a suit of clothes like the man leaning against the tree.

In the Squire's court everyone talks when there is something to say. The Squire can't be too dignified. He is a man of the neighbourhood. He stops the procedure of the court to borrow a chew of tobacco from the man accused. He and the Sheriff and the others will get the man if they can. It is a game. Most law cases, even in the higher courts, are a good deal that way.

In the case of Jim McGrew, the Prosecuting Attorney had something up his sleeve. He and the Sheriff had got Jim and two of his brood of kids on a country road at midnight two or three nights before. It is true there were no chickens in the car that night but Jim had in the car several empty bags and there was a heavy wire-cutter.

And, on almost any night, for two weeks, there had been chickens missing from hen-houses in just that neighbourhood. The hen-houses had all been stapled and locked and the staples had been cut with just such a heavy wire-cutter.

They had taken Jim and his kids to jail and one of the kids had talked.

Then afterwards, when he was brought into the presence of his father, the boy had tightened up. "Yes, I did say we stole the chickens but it was a lie," the boy declares now. He says he was bluffed into telling a lie.

There had been a trick played. They had made the boy think his dad had confessed. It is all right, the Prosecuting Attorney says, smiling at Jim, who smiles back at him, "We can't get you Jim, but we can get the kid."

He explains to Jim that he can send the boy up for what he calls "perjury". The idea frightens Jim. Perjury is a big, dangerous-sounding word. Jim gets up from his seat on the grass, his back against a tree in the Squire's yard, and calls his wife to one side. The Prosecuting Attorney is smiling at the Sheriff and the old Squire is smiling. They have got Jim. Jim's wife is a heavy woman with a shrewd face. She and Jim whisper together.

"They can get the kid for telling a lie, eh. Can they send him to jail? Well, I guess they can send him to the reform farm."

"Huh," says Jim, "one of my kids going off there, eh."

He comes back and calling t'he Prosecuting Attorney to one side holds another whispered convexsation.

The crowd is tense now. "You ain't got no case against me and you know you ain't, but I don't want one of my kids stuck. You went and bluffed the kid and made him tell a lot of lies. I'm an innocent man."

It is the Prosecuting Attorney who is smiling now.

"I'm going to get the kid."

"What is the least you will give me if I come through."

It is agreed that the Prosecuting Attorney will ask the Squire to be as light as he can on Jim and Jim confesses. It is to save his kid. They have got Jim this time but all the men in the crowd feel a certain sympathy for him. The Squire feels it too. He will let Jim off light.

And so Jim makes his confession to the Squire and to .the men and women gathered in the Squire's yard. He makes it as dramatic as he can. After all, even in a chicken-stealing affair there is such a thing as art, and Jim is an artist.

He tells how it was done, how he and the kids have been working, how he got Mrs. Sullivan's chickens and John Williams' lot. There was a night when he and his kids did a stunt. They stole the chickens of the Sheriff himself.

It was a night when the Sheriff was right at home and was sitting on his front porch. Jim looks at him and grins. He and the kids got the chickens right from under his nose. They had their car parked within a quarter mile of the house.

Jim is making the Sheriff cringe a little as he tells his tale. He takes a shot at the Prosecuting Attorney, too. "We would have got yours if you had kept any chickens", he says. Then he takes the jail sentence that has been agreed upon with his characteristic cold little smile and is marched off.

As for the people who have come to the trial, they all feel they have got a good show. They go away along the road talking it over.

"After all he stuck to his kid. If it hadn't been for him sticking to his kid they wouldn't never have got him," they say, as they go back to the fields and to their work in the corn.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now