Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Nowround robin

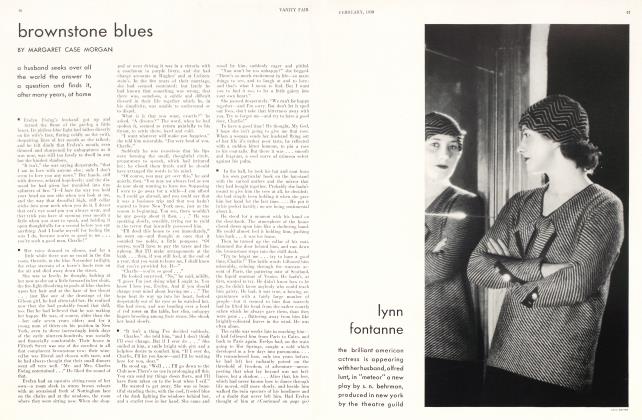

MARGARET CASE MORGAN

a thoughtful tale, in which a little too much of the feminine world loves a lover

Twilight came into the room like water flowing, a blue dusk, brittle with the noises of Paris but tapering, here, to silence, touching with fingers of wistful light the quiet face of the woman who waited by the telephone, her clear profile lifted against the blue air.

Waiting, she watched the liquid light thicken along the over-tapestried walls, obscuring the customary misfortunes in scarlet and gilt of a French hotel sitting-room. Only the telephone glittered, ebony and satiric and alone, in those soft scents and drifting shadows; but soon, Eugenia knew, it would ring and, miraculously, Robin would be there. Dear Robin, lonely in New York while she was so desperately far from him, in Paris. . . . Her gown, the colour of gardenias, shone delicately, reflected in a mirror on the wall, and the pretty thought occurred to her that she was like a figure carved in cool ivory upon the dusk, for she was a woman who liked to think in pastels. Contented, now, she closed her eyes to select the lovely words with which she would talk, presently, to Robin—words that, shaped and coloured in tenderness, would speed along the intervening wires in a pattern of delight as she told him of this twilight, of the young moon at her window.

Then, the background skilfully suggested, she would draw in a faint, enchanting portrait of herself. "My perfume is jasmine tonight," she would say, or, "I am wearing a dress as white as the moon"—definitely projecting, in a contralto current of charm, the picture, exquisite and unattainable, of her loveliness. And at the end, perhaps, there would be a final word, a last, perfect phrase spun vividly into space and according her hearer a little share in the enchantment born of herself. "My heart is lonely without you. . . ." or even, quite simply, "I love you. . . ." then a pause, the tragic click of the receiver, and silence. Eugenia, on such occasions, was irresistible.

Would Robin like her to be gay to-night, she wondered? Or whimsical, or perhaps a little sad? Dear, sensitive Robin. How brief their companionship had been—as brief as a sonnet, and as perfect. She remembered the dinner-party where they had met—her first appearance as a young widow, it had been, in a period when there are so few widows, either young or old. In a room clouded with smoke and cocktails and sharp laughter she had sat, alone and lonely in the cool perfection of her thoughts, until Robin had come and sat beside her; Robin with his brown, gesturing hands and his thin face with one eyebrow always higher than the other, as though it were shaped to the curves of his own enchanting mind. . . . They had talked of beauty, of rainy days and warm winds, of mad things like the cherry at the top of a coeur flottant—dwelling, all that evening, in a safe, enchanted place of their own building, with their mutual charm like a lovely secret between them. And, in the short weeks that followed, each day had been a bright thread woven into the texture of their companionship, a thread rooted in her heart and his until, one day, the thread had jerked and pulled until the pain in their hearts, they told each other, was unbearable. And that was the day when she had sailed for Paris, to take her small daughter out of school. She had contrived, then, to look so wistful, so entirely lovely, that Robin had gone quite pale with love for her. "Beloved," he had said that night, holding her hand very tightly a little before he left the boat, "you have lighted a candle in my heart that will burn forever." She could have wept for the beauty of that phrase. "One week from to-night I will telephone you," he had said, "at just this time, by your watch in Paris. . . ." And now, in the blue-and-silver evening, she was waiting, her mind and heart shaped to enchantment, rich with the lovely words she would give him.

The telephone rang. Her eyelids were heavy with smooth, grey ribbons of dusk as she lifted them.

"New York is calling, Madame. ... I will call you." The flat, staccato sentence did not touch the glamour of her thoughts as, again, she waited; and when the bell whirred a second time, she turned slowly toward it. An iris in a tall vase had broken, spilling its petals over the sleek, black metal, and she paused, held breathless for a moment by the charm of that picture'. . . even the telephone was clothed in beauty for Robin, she thought, her hand held eagerly upon the receiver.

^ "Hello! Eugenia?" said a voice quickly. "Robin. . . . Robin ... is it really you. . . ." Five minutes later, she turned on the electric lights and the room leapt at her in a nightmare of red and gold. Her face was white, sharpened in distaste. How could he. How could Robin do a thing like that . . . to telephone from three thousand miles away, to telephone over swift waters and through the dark night to her whom he loved . . . and then to spend the whole time in asking her to go and see another woman. It was crude, it was incredible. He had, she reflected tragically, scarcely allowed her to speak at all. "Eugenia darling," his voice had danced briskly along the wires, "I adore you. Do you love me? Well, then, be an angel and look up Ethel Pickering, she's divine. She's arriving in Paris to-day—the Ritz—you'll love her. ... I say, I haven't got much time left, but how are you?"

She had not answered that, however; she had been too wounded. But now, as she stood at the window and watched the pale splinter of moon above the Tuileries, she decided to see this Ethel Pickering. Ethel—what a name! Like an old piece of blue dimity with spots on it. But she would telephone this Ethel, and she would go to see her because it was the charming thing to do, and because it might be well for Ethel to see that the woman beloved of Robin was a little different from the Ethels of this dull world.

Charm was like a bright mist all about ® her when, the next afternoon, she sat at tea with Ethel Pickering in the gardens of the Ritz. She was a little disappointed, perhaps, because Ethel had not quite come down to the standard she had set for her. She was a square young woman with beauty in her eyebrows, and in her nose which seemed, in straight, perfect lines of defiance, always to be lifted against the wind. But she looked, there was no denying it, square; and Eugenia, thinking of Robin profiled against the moon, of Robin saying mad, lovely things about a blade of grass, found it impossible to think of Robin and this Ethel together. Thoughtfully, she introduced a strawberry into the perfect arc of her lips, and tried to listen to what Ethel was saying. It appeared that Ethel was interested in dogs, was going on to Germany to look at some Schnauzers. To Eugenia, who had once, for a season, made her appearance in public dressed exclusively in black broadtail and accompanied by a white wolfhound, dogs were an accessory to chic and nothing more; and a little wearily, now, she contemplated a small cloud, silver and powder-blue in the western sky.

Continued on page 122

Continued from page 66

"Robin," Ethel was saying, "was a perfect lamb about keeping two of my Schnauzers for me until I get back." The word Schnauzer, thought Eugenia dispassionately, punctuated this woman's conversation like a large, recurrent sneeze. She said:

"Have you known Robin long?"

"I met him just after you'd sailed, at a dog-show." Ethel's deep voice brimmed into laughter, and Eugenia waited coldly. She had heard enough about dogs; and she was curiously offended by the thought of a dog-show as a background for Robin, who had dwelt, with her, in the high abodes of loveliness. Ethel went on. "Poor Robin, he made a most awful mess of things that day. He was showing a shepherd bitch for some friend of his, and when they got to the field trials—you know, where the dog is told to pursue a man who's supposed to be an escaped convict or something—well, Robin commanded his dog beautifully until she'd got her teeth nicely sunk in the man's shoulder. And then, my dear, what do you suppose the idiot did?"

Eugenia's eye again sought the thin, far cloud. "What idiot?" she inquired, without inflection.

"Robin! He forgot the command to stop. He just simply and starkly forgot the words for it. And there was the poor fugitive being mauled until he was black in the face, with nobody to call the dog off." She sat back in her chair and laughed again, her fine nose broadening a little with laughter. "Robin simply collapsed. But I happened to be near him, and as I've shown shepherds myself, I knew the command; so I gave it to him. And after the show, it turned out that I was with some people he knew, so we went to a speakeasy and drank beer and talked about dogs." Ethel's eyes became reminiscent. "I told him quite a lot he hadn't known about distemper."

Eugenia sat very still, stiff with distaste. It seemed to her a caricature of Robin that Ethel had drawn, a portrait of an incompetent buffoon in whose burlesque antics she recognized none of the charm, the delicacy of her Robin. She lit a cigarette, and, remote among blue threads of smoke, replied:

"I didn't know that Robin was so interested in dogs."

"It's quite possible," Ethel admitted, "that he didn't know it himself until he met me. That's Robin's great charm, don't you think? He's the most entirely adaptable man I've ever known; he's so perfectly capable of sharing one's enthusiasms."

"Yes," said Eugenia, slowly, "he seems to be extremely adaptable."

In a little silence they sat there, these two women to whom Robin had so successfully adapted himself, and each one, in that silence, was thinking: "But this woman doesn't know the real Robin—the real Robin is the man who loves me. . . ."

Ethel took a pink cake from the tray on the table, and looked at Eugenia thoughtfully, even appraisingly.

"In fact," she said, "I sometimes wonder if Robin isn't perhaps a little too adaptable to make a good husband. . . ."

Eugenia's shoulder curved very slightly. "I haven't thought much about that." Her voice was firm, and she told herself that she was speaking the truth. Anyway, she didn't want to discuss Robin with this Ethel, this too, too sturdy creature.

Ethel appeared to be surprised. "No, of course you haven't. . . . Robin has told me all about your friendship for each other, and what a lovely, ethereal thing it was." She smiled companionably, and put three lumps of sugar in her tea; and Eugenia, chilled, wondered desperately if this woman beside her were thinking of marrying Robin herself. Had he asked her to marry him? Had he, with the flame of Eugenia bright in his heart, asked Ethel to marry him? "You have lighted a candle in my heart. . . ." he had told her, told Eugenia; but had he, she reflected, asked her, Eugenia, to marry him? Had he, in fact, asked anyone to marry him? Hadn't she, rather—and perhaps Ethel, too—hadn't they both, secure in the warmth of Robin's eloquence, concluded that this enchanting promise of eternal love could have but one ending? But which one did he love—Eugenia or Ethel? Eugenia looked at Ethel, and saw a square young woman; and at once her heart was lifted again among those small, drifting clouds whose silver plumes brushed the distant sky.

Continued on page 123

Continued, from page 122

"Of course, with Robin's enthusiasm," Ethel was saying, "anyone could marry him. He is the perfect bridegroom, eager and unafraid. And he does make love divinely—with words, you know.He told me," said Ethel, brooding tenderly upon the past, "he told me that I had lighted a candle in his heart that would burn forever. ..."

Dimly, then, Eugenia heard Ethel's deep voice raised in greeting, in presenting the Contessa Rossi. The Contessa leaned over the table, a woman done in long lines and thin upward curves like the drawings in the fashion magazines; a woman from whom conversation flowed without stopping in bright, ascending arcs of words and laughter.

"But, my sweet Ethel," she was saying, "when did you arrive in Paris? Yes, of course I will sit with you. . . . I just got here this morning. Yes, I've brought Pepi over once more to divorce him—isn't it triste? Poor Pepi, it happens every year. But he's done the same thing again—vanished like mist before the sun; I haven't set eyes on him since we got off the boat, although there are rumours that he's been seen in the Ritz bar. But who hasn't been seen in the Ritz bar?" A small sigh, scented with Chanel, escaped her. "It's too depressing; every time I want to divorce that man, he disappears. . . . Martini sec" She looked briefly after the departing waiter, and resumed:

"It's rather too bad this time, because I had such plans. . . . I'm in love. Yes, I am in love; with a most enchanting young man whom someone presented to me a little before we sailed. . . . not quite good-looking but with one eyebrow higher than the other, which is so engaging, you know. One feels constantly that one would like to straighten them for him as a task of love. And such charm he had. Although," she added reflectively, "he himself confessed that it was a little dimmed on the evening we met by the fact that he was all over dog-bites from some foul animals that a foul woman had left in his charge. But anyway, he told me that I loved him, which is so refreshing in a man instead of saying that he loves you—don't you think so?"

Continued on page 124

Continued from page 123

"Delightful," agreed Ethel in a curious, flat voice; and Eugenia, looking at her, saw in Ethel's face the toneless reflection of her own. The Contessa sipped her cocktail.

"So I had the divine idea of asking him to come to Europe and go with Pepi and me on a walking tour from Saint Mâlo to Mont Saint Michel, or some such trip—to find out if I really loved him as much as he said I did. It's a lovely scheme. The perfect triangle moving with slow fatefulness through the fields of Britanny. . . . But, as I told you, Pepi has disappeared again, and since I can't find him to divorce him or to go walking with him either, I'm afraid the whole thing's off. . . ." She sighed briefly, in tribute to a lost romance. "And do you know what he told me?"—the Contessa's bright voice deepened a little— "he said that I had lighted. . . ."

Eugenia rose, too swiftly. "I'm afraid I must go—I've some letters to write. . . ."

"So have I," said Ethel. "I've got to write to Germany," she added, unnecessarily, "about those Schnauzers. . . ."

Robin folded the three letters into a single envelope, and put them in his pocket. With the other hand, he arranged the motor-robe over the structurally perfect knees of the girl beside him.

"What a huge correspondence from Paris!" she observed. "Is that all one letter?"

Thoughtfully Robin turned the car up Fifth Avenue. "Fundamentally, yes," he said, "but the signatures are different. It's a sort of . . . round Robin." He smiled at her, his eyebrow curving in an accent of charm. "Where shall we go for tea?"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now