Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSquare-Cut Emerald

The Story of a Triangle Blurred and Broken by the Slow Winds of the Riviera

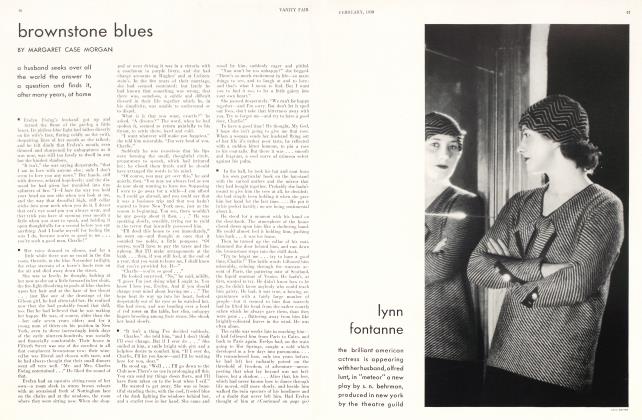

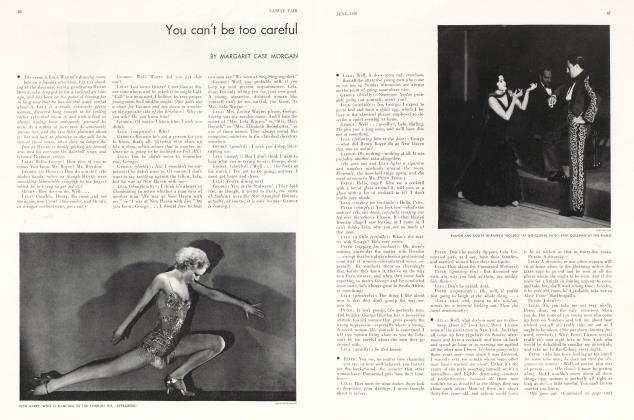

MARGARET CASE MORGAN

THE little floating shreds of coloured light, spun from a revolving ball suspended in the ceiling, dissolved like jewels upon the tinted walls, danced like petals over the gambling-tables; bubbles of citron, mauve, absinthe and crimson fantastically adorned a nose, a heedless chin, bit deep into the rich plush of rubies or enlivened the bland surface of a pearl; one even trembled, a triangle in gold leaf, in the depths of Cameron's liqueur. He lifted the tiny crystal goblet in his fingers where it hung as pendent as a tear. Green mint. So quiet, that liqueur, and so small —a little pool of emerald light in the sombre splinters of sound that filled the Casino. It was, he reflected, rather like Carol: radiant, and cool, and passionately alone.

Across the little table he watched her contentedly in the soft rain of colour. The pretty particles of dancing light did not foolishly invest her with gaiety; rather, she seemed steadily to shine through them, as a star can shine through fussy fragments of cloud. They touched her hair to deeper amber, warmed the pale, tranquil curve of her throat, but did not melt upon it. "Any more," he thought abruptly, "than fireflies could dissolve against the moon."

The moon. Lustrous thoughts of the moon filled Cameron. She was very like the moon, and should live there, he had told her once, absurdly. "With a little cream-coloured cloud for your pillow and the two smallest stars for your shoes."

Her reception of this had been deliciously grave. "I did live there once," she had informed him, with that curiously hesitant manner of speaking, as though each syllable were too soft, too lovely a thing to venture alone into a crisp world, "only I had to leave." She sighed. "My feet used to get so cold."

Delightfully he remembered this as he sat with her now in the Casino. He would have liked to tell her again about the moon, if they had been alone. But they were not alone.

The third person at the little table was a thin, gravely courteous man named Jollie, the proprietor of the Casino. And the fourth was Cameron's wife.

THE gambler's face was carved in thin semicircles of thought as he surveyed the tense little trio. Cameron was abstracted, sunk in the happy contemplation of illicit amour-, enormously protected by the soft wings of a love exquisite and unjust. The hair above his temples sprang upwards in small, expectant fans of pale grey; his eye, slightly prominent, was turned inward upon himself, romantically, and without reproach. With what ease, Jollie reflected, looking at Julia Cameron, men developed a sense of detachment when they wished to treat their wives badly.

Julia was bored, and lonely with the kind of desolation that obscurely comes to women like Julia in the presence of their husbands. Her face, in the swift, sliding colours of the room, swam brightly as a shell upon the sea, as emptily; her hands were pale, ineffectual curves. Only the small ridges in each shoulder where narrow bands of white satin, cold with diamonds, bit into the flesh betrayed a nervousness, a kind of tension. . . . She was, outwardly, the indulgent wife, schooled to the familiar consternations of marriage.

Jollie felt a vague astonishment that she should be so calm, so bright. Did it matter, he wondered, how bright she was, how calm, when across the table the woman whom Cameron loved shone like a flame, purely, remotely, in that glittering room? He knew so well the air of security that she wore—he had seen it in a thousand women. Women alone, without background, but women who were loved; women like water-lilies, detached and tranquil, drifting in a sharp excitement of clear waters, exquisite and unexplained.

He raised the liqueur glass to his lips, the green liquid curling frostily upon his tongue. "It's the colour exactly," he said, twisting the glass in pensive fingers, "of an emerald. A jewel set in the brow of a lonely goddess . . . the colour of loneliness."

"Loneliness?" inquired Julia, with that charming manner she had of being always ready to listen to anyone who seemed really fond of what he was saying.

"Emeralds," said Jollie, looking at no one unless it was, obscurely, at Carol, "remind me of lonely women. A tear shining on a blade of grass—bright with stolen colour, with fire stolen from the sun, but in itself—alone. It's like the detached, exquisite women whose only fire is kindled under the attention that wives have learned to do without."

CAMERON, wincing from an alien melancholy, became abruptly roguish. "No women will ever have to be lonesome while I'm around!" he promised lavishly. But he, too, looked at Carol. Lonely women? . . .

Webbed in soft colours from the whirling ball, Carol began suddenly to speak, her voice threading with a slow amusement the words she recited:

"A silver till if in a bowl,

The crystal stars above me,

A liquid eye, a shallow soul,

My lover doesn't love me.

"In chiffon shadows on the grass No beauty I discover.

A little fause—a tear—alas!

I dorn't care for my lover.

"That's a very cynical poem about lonely women," she concluded softly.

"It's about Women Alone," corrected Jollie, "which is often a very different thing. And it's about love, and beauty, and—impermanence, which is frequently another name for both."

"It's very sad," said Julia politely, after a little pause. She smiled brightly through liquid triangles of gold and blue light that fantastically caressed her, desperately exploded in her hair. . . .

Cameron looked impatiently at Jollie, at his pale eyebrows curved in revery. He would go on and on, Cameron supposed, about these Women Alone. There was something reproachful, almost something sinister in the way he spoke of them; as though they weren't quite— safe. He didn't, he decided, want to know anything about Carol, for instance, except that he was in love with her, and she, perhaps, with him. He wanted her as she was—unexplained, a lovely phantom, a flame of moon and mist dancing in the shrill delight of his mind.

Jollie was talking about emeralds, about water-lilies and impermanence. And now, Cameron felt, he was going to tell a story. He curbed his impatience, remembering that gambler's anecdotes were generally brief—with the briefness of disaster itself, he reflected grimly. And when it was over, he could take Carol out on the terrace, could be alone with her, frosted in quiet silver by the moon. . . .

This was the story that Jollie, sitting at the . little table amid changing shafts of silver and amethyst and powder-blue, told to Cameron and to his calm, bright wife, and, with a curious directness, to Carol Drake:

AT Saratoga, the season had begun. In the Ca-Z_A_sino, the gambling-tables were mute plateaux of despair, fringed with men and women alert as cactuses; fat hands and thin, electrified by the toneless cry of the croufiers, scrabbled noiselessly among the endless staccato whispers of chips. The players moved like birds on a wire, compactly. The girl, looking at them, noticed with detachment, how, with increased concentration, a diamond necklace would sink deeper into the folds of a pudgy neck, or a string of pearls start, as if in alarm, from a thin neck.

But it was on a thin boy crouched next to the croupier that her gaze remained the longest. The pale, upward gleams of a pile of gold in front of the fat man next to him mirrored themselves in frail yellow upon his cheek, but tragically produced no contrast, since the boy's face was of the same desperate tinge. Jollie, the proprietor, veiled in blue smoke near the tables, saw them bath. The boy was only about twenty, he decided, an unattractive little rat, but cocksure as the devil or at least, he had been before his luck turned. Now his thin face was calamitous, his little raw hands trembled as they grasped the chips. And that girl was watching him like a hawk ... or like a rabbit, Jollie reflected. Scared. Her eyes, beneath her shining amber hair, were bright, it seemed to him, with apprehension.

It was too bad; but what can you do, Jollie demanded of the end of his cigarette, when boys are fools, and their parents let them run off to all kinds of places? He sighed, and strolled around the tables, stepping lightly, a willow-wand of graciousness among his patrons.

Ten minutes later, the boy had lost ten thousand dollars; and, when Jollie looked for the girl again, she was gone.

She came to his office the next morning. She wore a little black hat over her amber-coloured hair, and she was pale. She moved lightly, tentatively, and when she spoke it was with a slight withdrawal, a kind of soft translation to some moonlit space beyond heaven from where, passionately alone, she looked upon the earth.

Continued on page 152

(Continued from page 78)

"Pm Mrs. Blake," she said, with that curious detachment. . . . ("Blake wasn't the name she gave me; she gave me the boy's name," said Jollie, "but Blake will do for the story".) She went on: "My husband lost ten thousand dollars in your Casino last night, Mr. Jollie," she said, "and I've come to ask you to give it back."

Jollie's eyebrows faintly curved with astonishment. "Unusual," he smiled.

She was very grave. "Ten thousand dollars can't mean so very much to you out of a whole evening, Mr. Jollie. And it means everything to my husband. It means ruin to him. You see—" —she leaned forward, sitting on the edge of her chair—"you see, the money wasn't his. He was keeping it for someone—in trust. It wasn't his. And now it's gone." Her voice was so quiet that Jollie couldn't be sure whether it was trembling. He frowned.

"It has been my experience, Mrs. Blake," he told her, "that gambling with other people's money is bound to end in disaster. If I gave the money back to you for your husband, neither you nor I know that he wouldn't do the same thing again."

"I know," she said quietly. "You see—I feel somehow that this is my chance to help him, to give him strength. We haven't been married very long, and I think if I can just start him fresh from this—episode—I know I can influence him, keep him strong, all the rest of our lives. Besides," she added, "Pm not asking you to do it for nothing. I—I thought perhaps we might exchange." She held out her left hand, a rather frail left hand, with a ring on the third finger. "It belonged to my mother," she said. She was very pale then.

Jollie took the ring. It was a square-cut emerald with a heart carved in the centre, a heart with long, slow drops of blood dripping from it, melting from it into the suave, liquid heart of the jewel; and beneath the carving was the inscription: uje meurs".

" 'I die' is a rotten motto for a Casino," said Jollie, with a grim smile. She had not urged him to take the ring; she sat in the barren little office as remote, as tranquil as a flower. But Jollie saw that her hands were tense.

"I'll keep the ring as security," he said, "and give you a cheque for the ten thousand; then, if your husband feels that he would like to pay it back some day, you can have your ring."

They were both thoughtful as he got out his chequebook; the details of the transaction were clothed, softened by. her moonlit stillness. She said, "We're going away this afternoon, so that I shan't see you again." And then she thanked him gravely, and was gone.

He was still thoughtful as he sent for his manager and gave orders that Mr. Blake, if he turned up again, was not to be admitted to the tables; his thoughtfulness had purely crystallized to doubt that evening when the boy came to him, heavy with dignity, his little face puckered with wrath.

"They tell me I can't play at the tables, Mr. Jollie," he fretted. "What do they mean? Didn't I pay what I owed last night?"

"Yes," said Jollie slowly, "and I gave the money bade to your wife for you this morning."

And then everything was made beautifully plain to the gambler, as Mr. Blake gasped and in bewilderment cried, "But I don't know any women here, Mr. Jollie. And Pm not married."

There was a little silence. Carol was playing with her lipstick, a tiny cylinder of platinum and gold, twisting it so that it shone in her fingers, a pale, metallic splinter of light. Jollie finished his liqueur.

"IPs odd," he concluded, "that I wouldn't know that girl now if 1 met her. AM I can see, when I think of it, is a white hand, white and frail, beneath a heavy emerald—a square-cut emerald with a bleeding heart, and 'je meurs'." . . .

It happened then. The lipstick rolled from Carol's fingers to the floor; she stooped for it; the thin, platinum chain around her throat swinging forward with the swift motion, its weighted end escaped from confining bands of silver cloth at her breast—and to the three who watched, it seemed that all the dancing bubbles of light in the room melted into one pure shaft of liquid green as they dissolved and broke upon the emerald at the end of that chain—a square-cut emerald, carved with a bleeding heart and the inscription, "je meurs" . . .

Julia Cameron flung her hand out toward it with a small, involuntary cry. The others were quite still.

Cameron lay in bed. Julia would be there presently, she had said. He suddenly wanted her. In the warm darkness he thought, with an increasing tenderness, about Julia. After all, a man's wife—he could be sure of her. The others were water-lilies, drifting, impermanent blossoms, lovely and too perilous. His mind was like a stem of a water-lily—groping for security. . . . He fell asleep, grateful for Julia.

Below the terrace outside the Casino, the sea was sleek with moonlight; moonbeams splintered and crashed in silver shreds upon the emerald in Carol's hand as she held it out to the other woman.

"Jollie gave it to me a year ago," she said. "I didn't ask where it came from. We. don't always ask, you know —we Women Alone." Her smile was a cold thread of moonlight. "But I didn't know it was yours until—I watched you while Jollie was telling that story. And I saw your face when you saw the emerald. ... I want to give it back to you."

Julia took it. It hung, for a moment, poised in silver; then it flashed through the air to the still sea below.

"I shouldn't like to have my husband hear of it," she said quietlv, "because it was only paste, you know."

Together, the two women stood there, beneath a moon urbanely carved upon a warm sky.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now