Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowExcuse it, please

MARGARET CASE MORGAN

Wherein it is demonstrated that a domestic triangle can be no stronger than its weakest central point

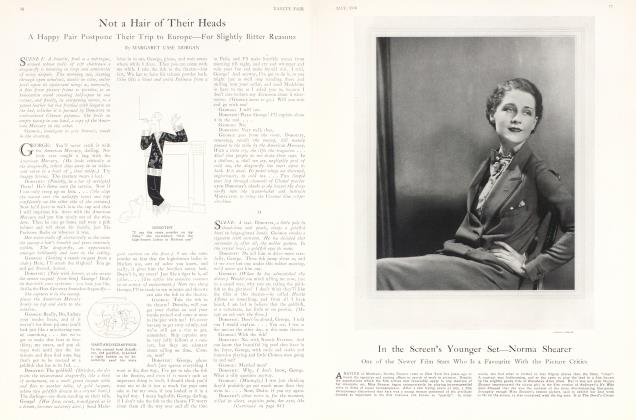

Mrs. Alfred Duffy lay in bed, in a frivolous sea of pink marabou, and looked at her husband without emotion. Alfred, having parted his hair and placed unguents upon it, was now brushing it carefully, a brush in each hand—two strokes to the right, two to the left. Upon the twin bed across from his wife's, his bag lay packed and ready for the usual fortnightly business trip to Boston.

The pale sun of a November morning drifted through the window to dwell timidly on the richness of the room, a pink-and-blue richness frosted with lace and with marabou and rose quartz; for Mr. Duffy was in the theatrical make-up business and, on the crest of a recent vogue, had made half a million dollars before you could say Florenz Ziegfeld.

His wife, now bringing her shallow blue eyes to rest for a moment upon a portrait that hung on the wall opposite the windows, was conscious that her husband's gaze had wandered there too. It was a portrait of himself, life-size and as accurate as though someone had sliced off the front of Mr. Duffy and pasted it neatly against the canvas—but with an added, sinister quality as well; for here the peaceful curves of the Duffy figure were exaggerated to an unhappy opulence, the friendliness of the eyes was lightly cartooned to a fawning anxiety. It was a portrait painted in skilful contempt of the sitter.

Mr. Duffy, however, did not observe these flaws in his likeness. He had never thought himself a handsome man, and he found sufficient enchantment in the gardenia portrayed upon his lapel, in the pearly gloss of the spatted feet. He liked to see it there, on the wall of the bedroom, it was a sturdy and proper background for the pretty laces and languors of Violet, his wife. And to see himself large upon his own wall gave him a comfortable feeling of presiding pleasantly over his home.

He finished dressing, kissed Violet briefly and picked up his bag. "I'll be home to-morrow night, Baby," he said, and paused before the portrait. "You're sure you don't think that painting ought to have glass over it?"

Violet's shoulder curved impatiently against a pink satin pillow. "It's dusted every day," she told him, "and -besides, people simply don't put glass over portraits."

He turned once in the doorway, his eyes peaceful upon the charming picture of his wife, his home, and the portrait smiling protectively on them both. Then he waved his hand, and was gone.

Violet, that night, was tearful in the smoked amber gloom of a familiar speakeasy.

"There's nothing the matter with one, Paul," she repeated, pathetically, "nothing except that—you don't love me any more."

Paul Baxter lit a cigarette. It was an accusation that he had heard from her so often that he no longer listened—so often, in fact, that he was sometimes inclined to agree.

"Do you, Paul? Don't you love me just a little bit, any more?" Her eyes filled with tears.

"Oh, for the love of. ... Of course I do, Vi," he told her fretfully, "only how do you expect me to, when you're always nagging and picking on me—"

"Picking on you! Oh, Paul darling—why, I try to help you. Why, I got you your first commission—to paint Alfred's portrait last year—"

"Yes, I know. You've reminded me of that before."

The silence grew between them. Once, their conversation had been made solely of mutual assurances of their love, and it had been enough; but beyond that, they had nothing to say to each other. And it was this silence that Violet had come to recognize, that filled her with panic. "I ought, to talk," she would tell herself, "I ought to be amusing." And then her tongue would stumble desperately into the old channel of tears and of discontent with the kind of love that she had found for herself.

She finished her highball. "I'm so worried, Paul. I don't know what Alfred would do— he's so proud of his home and his wife and everything. . . . Sometimes I'm afraid, Paul, when I think of what he might do if he ever found out about us." She touched her eyes with a handkerchief, and the mascara came off on it in a muddy streak. "You know, I was on the stage before we got married, and Alfred always thought that actresses were immoral until he met me." She was unconscious of the faint look of amusement that visited her lover's face. "And all this secrecy is getting on my nerves so, and that private telephone—"

Paul interrupted her. "Well, you had to have that," he explained reasonably, "unless you wanted your cook and the whole household listening in on you from the other telephones in the apartment. And I've always been pretty careful not to call you up when he was home."

"I know, but—"

"And anyway," he went on, irritably, "what do you suppose a scandal would mean to me? Have you thought of that? Have you thought what would happen to my career if every husband in New York was afraid I'd steal his wife?" He frowned, and lit another cigarette. "It would ruin me, artistically."

Violet's eyes dwelt incredulous upon this man who could talk of himself when her home and her life were at stake.

"Oh, this," she murmured dramatically, "this is the end."

He was silent. And in that haunted silence Violet was able to be thankful that she had found him unworthy. She would give him up. She would be a better wife to Alfred, the virtuous wife he -had always thought her. She would try to make it up to him. . . . When Paul had paid the check, she rose and moved with dignity to the door.

When he left her at the entrance to her apartment, they both knew that it was for the last time. But there were no tears in Violet's blue eyes now; they were lifted purely toward that new life that was to be hers and Alfred's. All through the next day she moved with an exaltation that was dramatic and complete; and the beauty of her emotion was scarcely dimmed by the knowledge that she had never learned to time her gestures of renunciation properly; whatever she sacrificed proved generally to be something that would, before long, have failed her anyway.

Violet Duffy extended her hand into the dark space between the twin beds and sought, by a series of playful murmurs, to impress her husband with the knowledge that it was there. He took it tenderly into his own.

"Good-night, Baby."

"Good-night, darling. I'm so glad you're home again with me."

Continued on page 82

Continued from page 29

Then, suddenly, into the stillness warm with sentiment, a telephone bell cut sharply, insistently once and again. Alfred disengaged his hand to pick up the receiver. In a moment, he put it back.

"'Number, please?'" he quoted scornfully. "I guess it was a mistake, honey."

But it rang again—and again, and the sound did not come from the instrument beside the bed. Mr. Duffy sat up and switched on the light.

"It's the telephone next door, dear," Violet finally found it possible to say. "If you'll just go out to the hall and listen. . . ."

"It is not," replied her husband flatly, getting out of bed as the bell rang sharply once more. He stood in the middle of the room, tracing the sound; and then he moved across the floor as it rang again. Now he was standing, incredulous, before the portrait of himself that hung on the wall

Now he had traced the bell. ... He was lifting the painting from the wall placing it carefully on a chair. . . He was opening a hidden door in the wall behind it. . . . The secret tele phone was in his hand. . . .

"Hello! . . . What? ... No, there' no Mr. Allison here. You've got the wrong number, madam—I say Cen tral's given you the wrong number There's no one by the name of Allisor here."

He replaced the receiver, in an in exorable silence turned and faced hi wife. Violet threw a white arm befor her face, as though to ward off a blow

"Alfred, I swear—", she shrilled.

"Shut up!"

The pink marabou trembled as Mi Duffy, his eyes too bright with un derstanding, moved slowly toward his wife.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now