Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTiming the golf stroke

ROBERT T. JONES, JR

America's champion advises about rhythm and gives us a few hints on swinging clubs correctly

It is unfortunate that the most important feature of the golf stroke is so difficult to explain or understand. We all talk about good timing, and faulty timing, and the importance of timing, and yet no one has been able to fix upon a means of saying what timing really is. The duffer is told that he spoils his shot because his stroke is not properly timed, but no one can tell him how to time it.

But one very common error which results in bad timing can, I believe, be pointed out with sufficient exactness to give the average golfer something to work on. I mean the error of beginning to hit too early in the downward stroke. I have said that it is a common error. It is an error common to all golfers, a chronic lapse in the case of the expert, but an unjailing habit in the case of the "dub". I believe it will be found that, of the players who turn in scores of ninety and over, ninety-nine out of every hundred of them hit too soon on ninety-nine out of every hundred strokes. Many golfers who play even better golf and have a really decent looking form, fail to play better than they do for this same reason.

Hitting too soon is, in itself, a fault of timing. It results in the player reaching the ball with a large part of the power of the stroke already spent. Instead of being able to apply it all behind the ball, he has expended a large amount of it upon the air where it could do no good. Apparently every man fears that he will not be able to strike out in time, when, as a matter of fact, not a single player has come under my observation who has been habitually guilty of too late hitting. Sometimes men fail to close the face of the club by the time the club reaches the ball, but this is a fault due to something entirely apart from tardy delivery.

The primary cause of early hitting can be found in the action of the right hand and wrist. If the left hand has a firm grip upon the club, so long as it remains in control, there can be no premature hitting. The left side is striking backhanded and it will prefer to pull from the left shoulder, with the left elbow straight rather than to deliver a blow involving an uncocking of the wrist.

But the right hand throughout the stroke is in the more powerful position. Its part in the golf stroke is what, in tennis, would be called the forehand. It is moving forward in the direction easiest for it to follow. Because the player is intent upon effort and upon hitting hard, the right hand tends to get into the fight long before it has any right to do so. The right hand must be restrained if it is not to hit before its time arrives.

I wish everyone could study carefully a few sets of motion pictures showing the proper action of the right side, noting particularly the successive positions of the wrists. In the case of an expert player the wrists remain fully cocked (just as they have been at the top of the swing), until at least half of the downstroke has been completed by the arms.

The dub, on the other hand, starts immediately, when coming down, to whip the club with his wrists. He forthwith takes all the coil out of his spring.

It is hard to wait, so long as the player is expending anything like the maximum effort. It is therefore wise to work yourself into this sense of delayed hitting, by swinging, at first gently toward the ball. I have seen numbers of mediocre players who were able to obtain fine results by exercising a bit of this kind of restraint. When once this sense is felt and the drives begin to crack sharply, one's speed and force can gradually be increased up to the player's limit.

A full and free body-turn, or pivot, as some people prefer to call it, is, of course, a source of great power in hitting a golf ball. It is impossible to accomplish a rhythmic stroke of any considerable force without understanding the use of the body and taking advantage of such an understanding. Arms and hands alone, even when assisted by some shoulder motion, cannot approach the power delivered by a controlled stroke in which correct body motion is present.

It will be observed that the more expert player upon reaching the top of a full swing presents his back fairly to the objective, until he is looking at the ball over the point of his left shoulder.

To begin the pivot early and to retain the right elbow close to the side of the body is to start at least, on the road to a fine shot.

But here I must speak of the importance of a full and free backswing. I feel that this phase of the golf stroke is worthy of further elaboration here, particularly because it is one in which nearly all golfers err when, for any reason, the responsibility of making an important shot begins to weigh upon them. The length of the backswing is one of the things which I have to watch continuously even when I am playing golf almost every day.

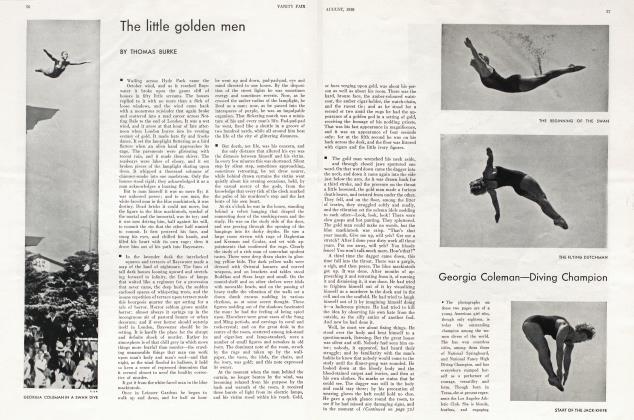

How the constabulary were forced to treat Bobby Jones in England, when he played in the championship there. The Bobbies had probably heard he made a habit of stealing holes, shooting eagles, smashing records and murdering par

Continued on page 32

Continued from page 62

Many authorities say that to take the club back so far that it passes the horizontal position is to be guilty of a fault which they call "overswinging." While I admit that it is physically possible to swing back too far—that is, so far that the balance of the player will be disturbed or his head pulled away from its proper position —I am still certain that the temptation or inclination to do so is not present to such an extent as to constitute a menace to the player. The average man's tendencies are all in the other direction. His desire, nine times out of ten, is to shorten his swing rather than to lengthen it.

The full backswing accomplishes one thing above all others—it gives the player time and room in which to start a gradual acceleration of his downward swing. It enables him to build up velocity, from zero at the top, to a maximum at impact without having to hurry. No swing can be smooth if the backswing is stopped at a point from which the club must be yanked downward with no chance to flow easily into the rapid motion.

In this connection I may digress a little to point out that more short pitches are missed because of an abbreviated backswing than for any other reason. The player has been told to limit the length of the shot by limiting the length of the stroke and in no event to soften the force of the blow. In attempting to play a short shot firmly he invariably chops off his backswing and ruins his timing. He need not, indeed should not, employ a full swing for a short pitch, but neither must he get the idea that the length of the swing should be only half when the length of the shot is half. In any case the club must be taken back far enough comfortably to accommodate the blow to be delivered. The club must be given time to gather whatever speed it is intended to attain.

The initial movement in the golf swing (that which starts the club travelling away from the ball) has always been a puzzling one to describe. The whole thing occurs so nearly simultaneously—with the hips, arms, hands and clubhead starting to move at so nearly the same time—that it is difficult to determine just where the motion originates.

One thing revealed by fast motion picture photography is that nearly all expert players permit the clubhead to lag behind the arm motion during the first few inches of the backstroke. Pictures showing the player's position when the clubhead has travelled only a few inches show that the hands have travelled farther and that the shaft of the club no longer occupies the same position with respect to the arms as at the time of address, but that the wrists are flexed slightly backward toward the ball. This is an indication of two important things: first, that the motion of the swing originates back of the hands and wrists; and second, that there is perfect relaxation, permitting the weight and inertia of the clubhead to make itself felt before it is flung back to the top of the swing. In describing this feeling, the pro will tell his pupil that the clubhead should be "dragged" away from the ball or that it should be "flung" to the top of the stroke.

That the first motion of the backswing should be made by the legs or hips there can be little doubt. To start it with the hands inevitably results in the lifting upright motion characteristic of the beginner who swings the club as though it were an axe, elevating it to the shoulder position without a semblance of the weight-shift and shoulder-turn effected by good golfers. But there are various opinions concerning the best way consciously to begin the motion.

George Duncan believes that the swing is begun by the knees—that the player "takes off" from the left foot by employing a quick knee action and swings the weight over to the right foot. This is all right and may in certain cases be true enough. But the trouble is that when the player actually puts his mind upon knee motion and upon shifting the hips first, he is more apt to pull his entire body backward and settle, his weight upon the heel of his right foot before his club gets anywhere.

It is all-important that a correct; start be made so that the player will be in position, at the top of the swing, to deliver the blow in the most efficient; manner possible. To be able to do. this his weight must be back of the; ball and his club must be in a position to be swung around against the; ball and not to be chopped down upon it. To accomplish the first of; these the shift of weight to the right, foot is imperative, and obviously it is. a more easily controlled action if the: order is "shift, turn," rather than, "turn, shift," for in the latter case: all sense of balance would be destroyed. The correct position of the: club—the second factor of importance: —is more easily accomplished in the: manner described, because the shift of. weight pulling the club away from, the ball, at the same time causes the clubhead to come away inside the line of flight, the very opposite of the chopping stroke referred to.

I of ten.believe that to start the back^ swing correctly is one of the hardest; jobs the beginner has to accomplish* It is always easier to follow a motion correctly started than it is to steer it into the proper direction. There is a confusing something about takingoff from a position of rest which leaves, the average beginner in a state of! helpless perplexity.

It is always best for us to consider the golf stroke as one flowing and; uninterrupted motion backward and. forward from the position of address, through the ball to the finish. This, view is far more valuable than that which regards the swing as a seriesi of distinct motions.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This is one of a series of articles on golf by Robert T Jones, Jr., which is published here with the consent of the Bell Syndicate, Inc.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now