Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowCountry life in Europe in Europe

PAUL MORAND

Visiting on the continent observed by a Frenchman who has lived through a thousand gay week-ends

It is a comparatively simple matter, in Europe, to own a chateau; in fact, there are ancient strongholds in Italy and southern France that can be had for a few hundred dollars. It is rather more difficult to own motor cars. It is almost impossible to have friends who are willing to climb into your motor cars with you, and go driving off to your chateau.

Generally, a chateau is not purchased; it is a curse handed down by one's family, a sort of hereditary disease. Only Americans can really enjoy one, for they do not inherit their chateaux; they rent them. They do not know what tremendous sums can be spent in repairing a roof, or in breaking through a twelfth-century wall with tools that are scarcely less ancient. They can also ignore the animosity of the peasants, the feuds between neighbours, and the various forms of rural theft that go by the names of leases, fermage, metayage, tithes. . . . Happy indeed are the Americans who reach their chateaux on a fine summer day, play tennis (if the grass court isn't transformed into a hayfield), plunge into the swimming pool, and sail home on the Mauretania at the first sign of frost. "My dear, I had such a lovely place in Normandy this summer, and so cheap, too. . . ."

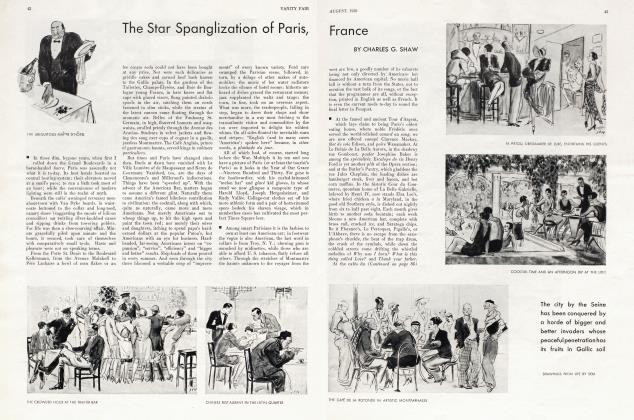

Every nationality has its own ideal of chateau life. The French, for example, are notorious for their horror of nature, as all their literature goes to prove. The French garden, with its upholstered look and its decorative effects, is made to be gazed upon from a window—from a closed window, of course. The French country house is silent most of the day; the ladies are reading or writing in their rooms. Shortly before dinner, they appear in the salon, where a brilliant, witty, and malicious conversation is carried on by people who have never felt the slightest wish to hear the song of the nightingale, or to trip through the dews of morning. It is true that the hunting clothes of a few determined sportsmen may bear, occasionally, the frightful odour of woods and soil, but all the other guests will have ridden to hounds in a carriage, with books on their laps.

The dinners are like mediaeval feasts. There is a superabundance of game—for what has been shot must naturally be eaten—but there is nothing to do afterwards, except to wait for the next meal. The host has one amusement: he can clamber down to the cellar with his keys and select a cobwebbed bottle from the old wines bequeathed him by his ancestors. He must rise, however, at break of day, and set a good example to the peasants by hearing mass. Shortly before dark, he must have a pony hitched up and driven to the station, since one or two of the guests will now be returning after a few prudent hours spent in the heart of urban culture. . . . And so, for two weary months, Frenchmen buried in the country impatiently await the signal for their return to Paris.

There are two distinct types of Italian chateaux: the château-fort, or castle, which dates from the Renaissance, and the chateau de plaisance, or villa, which dates from the eighteenth century. The first is approached over impassable roads, but even after it looms into sight, you have hours of patient climbing in front of you, for the castle is a sort of eyrie, perched high on the mountainside. Night has already fallen, and the lord of the manor, whose only distraction has been to follow your painful progress across the plain, now suddenly lights a thousand flaring torches on his battlements. It is a splendid moment; you are proud of having a friend who has been cradled in so rich a past. You feel as if you were returning from the crusades. At last you reach the moat, where the donjons tower above you, red in the torchlight. You enter by a narrow drawbridge, to the great detriment of your mudguards. A terrific uproar greets you—for, as in times past, the whole population of the village inhabits the castle. You wander through endless corridors which are completely denuded of furniture (it has all been shipped off to Hollywood where it adorns the Hotel Ambassador). You pass beneath terrifying heraldic devices carved in stone; you scurry through vast and glacial rooms where ancestral portraits glower down at you suspiciously. Finally, in the Guard Room, amid red silk hangings, ebony and ivory furniture, forged steel weapons, and instruments of torture, you are greeted by your host.

You are then escorted to one of the eighty bedrooms. It is lighted by a tiny window, and they warn you it is haunted. Here you are abandoned. "It's a simple matter," they tell you, "to find your way. Follow the Corridor of the Popes, then turn to the right and climb the stairway that leads to the Gallery of Roman Emperors. Just beyond the bust of Tiberius, take the corridor on the right, and the fifteenth door to your left leads into a hallway and your bedroom decorated by Mantegna is at the end."

Later, when you decide you will take a bath —there is one tub for every fifteen bedrooms—you retrace your steps through the corridors toward a sort of hall as spacious as the waiting-room of the Pennsylvania Station. Sunk in the marble floor of this hall is a Roman bath, into which you descend by a flight of stairs, as if you were entering a tomb. Water as red as blood, and icy cold from having passed through the glacial walls of the castle, trickles on you dismally from a faucet. In vain you call for a servant; nothing answers but the echo, and your voice trails off into infinity. The shades of incestuous popes, the ghosts of blood-thirsty condottieri, hover about as you slip your trembling body into the cold, stiff, gleaming bag that is your evening shirt. Clanking chains ring in your ears as you grope through the corridors toward the grand salon, where whole trees blaze in a fireplace that roasts you without yielding any real warmth. Wind moans among the flickering tapers, as in The Fall of the House of Usher. . . . Your sleep is haunted with nightmares, and you resolve to leave at dawn. But alas! it has rained during the night; the mountain torrent has become a river too deep to ford, and there are no bridges. You must therefore return to your haunted chamber, and in the canopied bed like that of Desdemona, wait for better days.

The Italian chateau de plaisance is more cheerful, but the roads to it are just as impassable. After leaving your car in the court of honour—which the village has taken over and transformed into a marketplace full of corn in golden heaps and scrawny hens tethered by their legs—you are swallowed up by a monumental door. The walls of every room are covered with frescoes; not a square foot is left unpainted. There are the Room of the Navigators, the Room of the Horses, the Room of Celebrated Philosophers; even the ceilings sag with the weight of allegorical figures. Your hostess apologizes: "Italy is really no place to entertain. The foie gras hasn't come from Paris, and the grouse missed the plane from London." You are therefore condemned to spaghetti and polenta. As for champagne, Mussolini has just forbidden its importation, and you are reduced to drinking asti spumante in its sweetest and most Italian form. Beneath you lies the valley, a sweltering furnace where no one would dare to risk his health. So there is nothing left but to stroll in the garden, or investigate such ancient curiosities as the labyrinth where laughing girls spy on you, invisible though near, and the moving bench that squirts a stream of water over you as soon as you sit down—a device which proves that the pleasures of Coney Island are not strictly modern inventions.

In the evening the village youths arrive with a little orchestra of mandolins and accordions led by an ill-shaven priest, while the little boys run to set off fireworks on the hill in back of the garden. These beautiful green skyrockets, the secret of which was stolen by the Italians from the Chinese, and these Bengal lights that gleam like the furnace of an alchemist, reveal the frescoed pavilion where cardinals and popes used to take their daily siestas. Its ceiling, on which Tiepolo painted a host of blackamoors, has crumbled away, and the stone figures representing the gods of forest and river are eaten with yellow lichens.

Continued on page 70

Continued from page 24

In England, the country house is not abandoned in headlong flight at the first autumn frosts. On the contrary, its life begins with winter. Rain, snow, and draughty rooms have no terrors for the country squire. Riding to hounds imparts the glow of romance to his life. Should you arise late, when all the huntsmen have taken to the fields, and thus be left to play bridge with former ladies-in-waiting to Queen Alexandra, you will miss the true significance of these ivy-clad Gothic structures, built under the influence of Sir Walter Scott. In England you must hunt, or at least ride. The icy rooms, the snow that seeps in through the windows, trouble the apple-cheeked sportsman not at all. He is kept warm by his great meals, by foaming brown ale and by his day in the saddle.

And castles in Spain? Even an Italian villa, to be enjoyed, must be owned by an American who has spent many years in Paris; so what can we say of a castle in Spain? They exist, and some of them are very lovely, but they are almost totally inaccessible. Occasionally you will come across a Spaniard who invites you to his hotel, but the Spanish grandee who entertains foreigners on his estate is still to be found.

In Spain there are the great eighteenth-century chateaux in the foothills of the Guadarrama, most of them built in the style of the royal residence at la Granja. The castles of Aranjuez, which are about as gay as the Escorial. The little Renaissance manors on the banks of the Guadalquivir, each one of which claims the honour of having sheltered a mistress of Don Juan. Basque strongholds visited in summer by motor car from San Sebastian or Sentander, and the villas built by new-rich Catalans, in a style that is Mediterranean and international. Chamois hunting in the Pyrenees, and the austerity of monasteries perched on inaccessible cliffs. The charterhouses of Majorca, the groves of African palms in Elche, veritable prisons for great noblemen in disgrace. Nowhere, in Spanish chateaux, can the joy of living be found, save perhaps in Andalusia, during the springtime, on those ducal estates where bulls are raised, and where the amateur bullfights, the novilladas, remind one of the rural sports pictured on Goya's tapestries.

German chateau life was not destroyed by the war; indeed, the case is quite the reverse, for the landed aristocrats weathered the defeat and the period of inflation by taking refuge on their estates. However, with the disappearance of the Emperor, their life was deprived of its significance. . „ . The Kaiser is expected! Throughout the year, the counts, the dukes, the princes, lived for the moment when, with his pointed moustache, with his withered arm hidden in a green cape, he arrived for the hunt. Though the Kaiserin never accompanied him, he was attended by a brilliant retinue. All the nobility was invited to great house parties, which were surpassed in luxury and formality only by certain Russian receptions, and which made English hospitality seem drab and rather bourgeois in comparison.

In Austria and Hungary, the social life resembles that of the German nobles, but the chateaux are still feudal. They are of the soil and for it, and they exist as intermediaries between the pleasures of the West and the monotony of Russian country life. Csardas danced till dawn; stupendous drinking bouts; rich displays of velvet and sable uniforms. . . . About you lies the plain that stretches into the distance, the great wheatfield of the Danube, dotted here and there with clumps of acacias.

Rumania alone, of all the Balkan countries, has chateaux that are worthy of the name. The life led there is interesting from the historical point of view; it is our last reminder of Holy Russia as depicted in Gogol's poems and Anna Karenina. The Rumanian boyars were provincial, it is true, in comparison with the Russian nobles, but they were untainted by Western ways, and to-day, in spite of the neighbouring Bolsheviks, in spite of the radicals clamouring for a division of the great estates, and in spite of the ravages of war, the Rumanian chateau still exists. However, it is neither a chateau, strictly speaking, nor yet a simple farmhouse; it is a vast, unpretentious dwelling lost in the midst of the plain. Life here in summer—except for a few eccentrics, no one lives outside of the cities in winter —is tame and frugal.

The dismemberment of estates, the disappearance of thrones, the scarcity of farmhands and servants, the migrations of the ruined aristocrats who have been forced to earn their living in the cities—all these tendencies have little by little deprived European chateaux of their ancient prestige. Built in an age of permanence, they will astonish tourists for long years to come, but they are dying from within; they are not reared for this era of small fortunes, of cheap automobiles, of palatial hotels; nor for the youth of this age, who demand costly, intense pleasures, shared in common and changed each day. The new generation will rarely visit these mansions of French stone, these halls of English brick, these fortresses of the Quattrocento, save when some troupe of movie actors on location peoples them for a moment with painted nobles and great ladies with straw-coloured hair, directed by an exacting emperor with a Jewish name, clad in shirt and voluminous knickerbockers, who shouts his orders through a megaphone. . . .

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now