Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTwo Systems of Calling at Auction

A Discussion of the Differences between the American and British Methods, with the Advantages of Each

R. F. FOSTER

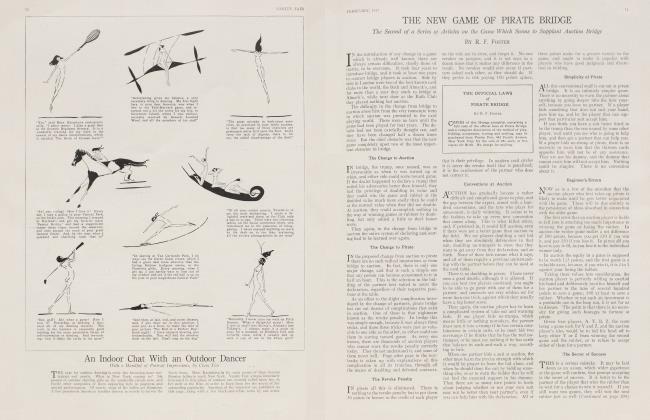

AT the beginning of another Winter, during which more bridge will probably be played than ever before, we find the players divided into two great camps, each depending on a different style of weapon with which to wage the millions of coming contests at the card table.

Whether the superiority of one over the other will ever be settled is doubtful. Human nature is opposed to universal agreement in anything. In the old whist days it got down to the long-suiters against the shorts, and neither could convince the other, although all the shorts were converted from long-suiters. A magazine published largely in the interest of the long-suiters arranged a duplicate contest by correspondence between sixteen of the leading exponents of each system, but it was abandoned toward the end, when the shortsuiters were about two hundred tricks in the lead, and the results were never published.

Perhaps if a similar contest could be arranged between the two leading schools of calling at auction today, we might find out something. . Some persons distinguish them by calling one American and the other English; but neither country uses either system exclusively. It is only the writers on the game that suggest the distinction.

So far, no one has suggested an appropriate name. One writer suggests calling the American idea "the suit system", and the British method "the hand system." The difference between them is briefly this:

Both believe there should be a definite minimum of strength in the entire hand, and agree upon that minimum.

There is little difference of opinion about no-trumpers.

The American writers insist on the caller having the chief strength, or at least more than half the minimum, concentrated in the suit which is named in a free bid.

The English writers believe in calling the longest suit in the hand without regard to its individual strength, provided the whole hand is up to the required minimum.

Two examples will make this clear: The American writers recommend calling a heart on the first of these hands but they say that the other hand is either no-trump or pass. The English writers would call a heart on the second, but not on the first. They are still in the stage that demands outside tricks, even with five to the ace king. Many American players are also still of Aat mind, although the writers believe in calling in the ace king and three small. It took Milton Work some time to get down to it; but he finally had to fall in line, and now recommends calling on five to ace king, even with nothing outside.

The minimum in both systems is agreed upon as being a hand as good as average, ace, king, queen, jack, ten; or as good as two sure tricks, and five cards in the suit called. Writers differ slightly, however, in their minimum strength for the suit named. American writers insist on ace jack at the top. Bergholt, most conservative of the English writers, says king jack, and points out that Milton Work gets down as low as king ten. Other English writers get down to the queen ten.

Ernest Bergholt, who is card editor of the London FIELD, puts the situation this way, in a letter to this magazine:

"My minimum of king knave and three small, is, of course, entirely arbitrary, but one must fix a limit somewhere, and other English writers accuse me of being oldfashioned for not putting it lower. My principle is that if the suit called is as weak as this, there must be at least an ace and a well guarded queen and ten outside to bring the whole hand up to average strength. For example:

"The principle in bidding is that as the strength in top cards diminishes in the suit called, the outside strength must proportion ately increase. It remains to fix an inferior limit, beyond which the top-card strength in the suit called must not fall. in

"My minimum is king knave to five, It as plain that just as soon as we fix a minimum it will be possible to show many cases in which calling on that minimum leads to unfortunate results; but that does not disprove the soundness of the rule. A higher minimum would not guarantee against occasional loss. A sound minimum is one that will show a balance of gain over a long sequence of deals. For example; if you call on king knave, it is 5 to 4 that partner has ace or queen, and 17 to 2 against both those cards being on your left."

The point about the English system of calling on the whole hand is that it depends on the law of averages. If the length and strength is all in the one suit that the caller names, he is no better off than the player who has simply length in the suit called, but has strength scattered through several other suits. Such players would much prefer to call hearts on five to the queen ten, with tricks in two other suits—ace jack in one and four to the king in another—than they would to call hearts on the ace king, with eleven small cards.

"What difference does it make," they ask, "whether you lose a trick or two in the trump suit, and win them elsewhere; or win them in trumps and lose all the others?"

For the benefit of those who are not familiar with "the hand system," and may wish to try it out, the following details are given, showing wherein it differs from the "suit system" as commonly recommended in this country.

To call on four cards, they must all be honors. If these miss the ace or king, there must be at least queen jack in a side suit.

To call on five cards, the whole hand must average as good as ace, king, queen, jack, ten; with at least king jack in the suit named. Some writers recommend even weaker, for examples:

To call on six cards, Aere should be ace, or king queen, at the top, and one sure trick outside. If the six cards are only king jack at the top, there should be an ace and a queen jack suit outside, at least. For example:

In calling two-suiters, the mere fact that there are two suits, and Aat it is desirable to show them both, prompts calling on much blow minimum. One writer gives this

Continued on page 98

Continued, from page 82

In calling two-suiters, the mere fact that there are two suits, and that it is desirable to show them both, prompts calling on much below minimum. One writer gives this example:

One writer gives the following as sound original heart calls by the dealer:

On the other hand, the English writers advise against calling minor suits without length, and apparently disregard their value as showing assistance or defence. The following are given by one of the most liberal writers as hands to be passed up:

Almost any American player would call a club on these, if not no-trump on the third.

The argument put forward by Gillies, is that it is the bold or forward caller that wins. He comes a cropper every now and then; but in the long run, Gillies thinks, he will get away with contracts that a more timid player would never try for.

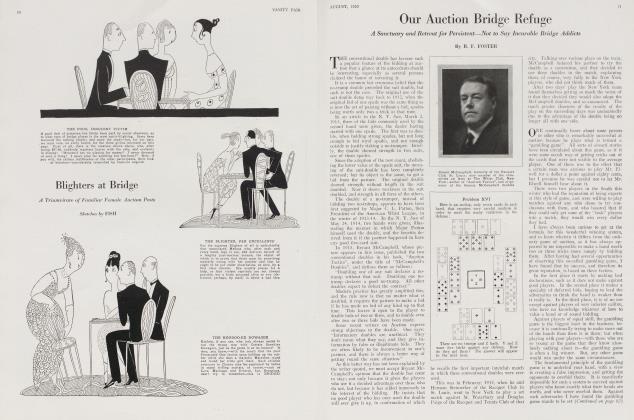

Answer to the October Problem

(Owing to a mistage, the problem in the October issue was wrongly stated. B should hold the. jack of diamonds; not the king. The answer here given is intended for the problem as correctly stated.)

This was the distribution in Problem XLI, which was a very tricky proposition, full of false leads.

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want five tricks. This is how they get them:

Z leads the spade king and follows with the trump, which Y wins. B's best discard is a diamond. Y leads a small club. If B puts on king or queen, Z wins with ace and leads the queen of diamonds. If A covers the diamond, Y trumps and leads the losing spade, which B wins. Now Y must make a club trick.

At the third trick, 2 may refuse to play a high club. Then Z let; A win with the nine. Having nothing but diamonds, A must ether lead the ace to kill Z's queen, or lead a small one and let the queen make. If he leads the ace, Y refuses to trump it, disdiscarding the spade. If A wins and retrumps. What will B discard?

A very promising opening which will not solve is the queen of diamonds Y dfccarding the spade. If A wins and returns the diamond, Y and Z can separate their trumps, which solves easily If A leads his trump, instead of returning the diamond, Y wins and forces a discard by leading the other trump. As B cannot afford to weaken his spades he lets go a' diamond and a club', Z discarding a spade, if B keeps that suit. Now a club from Y is won by Z, who returns it and makes the third club by getting in with the spade king, which solves.

If A returns the club, instead of the diamond or the trump, the same thing happens, the tricks coming in a slightly different order. Z wins the club and leads the trump, Y forcing the discard from B with the second trump, and Z makes the third club later. This variation solves.

But the diamond opening is nevertheless unsound, as it can be defeated by A's winning the first trick with the ace and leading the spade, which B refuses to cover, and which Z must win. Now if Z leads the ace of clubs and follows with a spade, A will refuse to trump the spade, and Y is forced to lose two club tricks if he trumps it; or a spade and a club if he does not.

Z cannot get out of this by leading the trump upon winning the second trick with the spade king, because even if Y wins the trump and leads the club through B, and Z lets B hold it, B can wriggle out of the trap by leading the winning spade, forcing Y to trump it, and then covering whichever club Y leads next.

Another false opening which many thought would solve is the trump, B discarding a diamond. Y wins the trump and leads a small club. If B puts on the. queen, he is allowed to hold the trick. If he leads another club, Y's eight will be good. If he leads a diamond, the ace falls to Y's trump, and two rounds of spades force B to lose two clubs. If B leads a spade, Z comes right back with it, with the same result.

If B returns the spade, instead of the club or the diamond, Z will put on the king and lead a diamond, allowing Y to -trump and lead another spade, throwing B into the lead again, and forcing him to lead away from his clubs.

But the trump opening can be defeated if B ducks the first club trick, letting it run to A's nine. If Z puts on the ace, both B's clubs are good. If A is allowed to win with the nine, he leads the ace of diamonds, and if Y trumps it, B must make a club and a spade later.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now