Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOur Auction Bridge Refuge

A Sanctuary and Retreat for Persistent, Not to Say Incurable, Bridge Addicts

R. F. FOSTER

A HAND was quoted in the March number in which only one pair out of a dozen or more in a duplicate match succeeded in winning the game, although it was possible to win it against any defence, and attention was called to the fact that just winning game,or saving game, was the surest mark of a fine player.

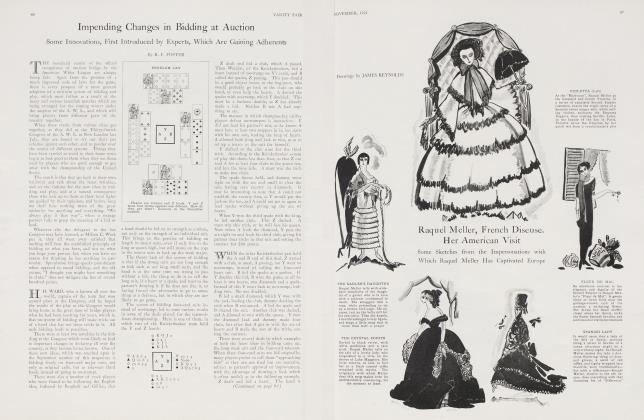

A large number of the readers of this magazine have responded to the request for an expression of their idea as to how this hand should be played, among them one of the clearest and most logical is from Major C. L. Patton, ex-president of the American Whist League, whose picture appeared in these pages for June, 1919. This is the distribution:

The final declaration was hearts, by Z, and A led the spade queen. The problem was to get four by cards against any line of play after that. This is how Major Patton accomplishes it.

A must be allowed to hold the first trick. If he continues with a spade, Z wins and ruffs dummy, putting himself in again with the ace of diamonds to ruff dummy again, but this time dummy trumps with the ace, as B is marked with no more spades. Y then leads the queen of trumps, which B wins.

If B now leads a club, dummy wins with the king and leads a small diamond. It does not matter which side wins this trick, but suppose B holds it with the nine. If he leads another club, Y wins it and leads the third diamond for Z to trump, and Z makes the rest of the tricks with the trumps.

If A switches to the trump, after being allowed to hold the first spade trick, which is probably his best defence, dummy must put up the ace second hand, so as to prevent two of his trumps being drawn before he gets the spade ruff. The lead of the small spade puts Z in, and another spade gives Y the ruff. Z gets in again with the ace of diamonds, and leads his last spade, which dummy trumps with the queen, over-trumped by B with the king. Now the top diamond is the only possible trick remaining for A and B.

This is a peculiarly instructive hand, as it shows the importance of the principle that if two losers in the adversaries' suit cannot be discarded, the hand should be so played, if possible, that dummy shall trump them.

The Man from Missouri

AT every winter resort in the South there are some persons who acquire the reputation of being the best bridge players, if not at the hotel, in whatever town they happen to be from. This is either because they have had a few lucky days in the early part of their stay and won almost everv rubber, or because they talk learnedly about the modern conventions of the game, and have impressed the average person with a sense of their importance.

Here is an extremely interesting end game, in which there are eight cards left in each hand. It is instructive in showing the importance of providing, in advance, for any side jumps the adversaries may unexpectedly make:

Problem XIII

There are no trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want five tricks. How do they get them?

The answer to the April problem will be found on page 102.

In some such way Mr. Luckton-Wells had acquired the reputation of being the best player from a well known club in Boston, and had found in Mr. Winston-Smiles an attentive and appreciative listener, who agreed most heartily with all the learned expositions of the finer points of the game. So much so, in fact, that Mr. Luckton-Wells somehow formed the idea that Mr. Winston-Smiles was an adept at the game. As there were no other members of either club to which these gentlemen belonged on hand to alter this opinion, it was allowed to stand.

LOUNGING in the chairs in the hotel lobby after the day's golf was over, the conversation happened to turn on bridge, and Mr. Luckton-Wells was trying to convince a gentleman from Missouri of the great advantage of certain conventions, such as playing down-andout, unblocking, making re-entries, getting in twice for double finesses, and a number of other things which he had lately absorbed from a little book entitled "Winning Bridge", by a woman teacher in Waukegan.

Not being able to convince his acquaintance that there was anything in it, he was continually confronted with the statement that the man who held good cards and played a "backwoods game", without bothering his head about any conventions, would win all the time.

A number of listeners being apparently interested in the argument, a little friendly match was suggested, the man from Missouri to get his own partner, who happened to be from Texas, with no reputation as a player, while Mr. Luckton-Wells would get Mr. WinstonSmiles and they would demonstrate the superiority of the conventional game.

Nothing unusual happened for the first rubber or so, and the gallery was beginning to lose interest, except those who had side bets on the result, when this hand came along on the rubber game:

The man from Missouri, having the deal, bid no-trump, which the others passed. Mr. Winston-Smiles led a small diamond, which was won by the ten. The problem being to make the club suit, the man from Missouri proceeded to lead out the ace and queen, hoping to drive the king before he lost dummy's spade ace, his only re-entry.

Having no clubs, Mr. Winston-Smiles proceeded to discard the small diamonds, hoping to stop the spade suit with four to the nine probably. This gave the man from Missouri pause for a moment, but he followed the ace of clubs with the queen, mentally regretting that he had not started with the queen instead of the ace, instead of assuming that the clubs were split.

The alleged champion from Boston studied the situation for a moment, and saw, or thought he saw, the importance of killing dummy's reentry before the clubs were cleared, and as the declarer still blocked that suit with the jack, Mr. Luckton-Wells won the queen of clubs with the king and started leading his high spades, to force out the ace.

The man from Missouri allowed both the king and queen to win, by holding up the ace of spades; but when the third spade was led, he promptly discarded the jack of clubs upon it. This allowed him to make all the clubs, winning the game and rubber.

"You should have let that queen hold, partner," remarked Mr. Winston-Smiles, reprovingly. "Let him make his jack, then he will have to come to me in diamonds, or to you in hearts."

"If you play the second-best echo, putting your six of spades on the king, as I explained to you yesterday, and then play down, showing me four in suit, I shall be aware that the player on my left has no more and will get a discard," retorted Mr. Luckton-Wells. " Then I shift, putting him in with a small club, and we set him two tricks."

(Continued on page 102)

(Continued from page 81)

"I am not sufficiently familiar with the plain-suit echo, I fear," apologized Mr. Winston-Smiles.

"The system does not seem to work very well tonight," was the only comment of the man from Missouri; who was adding up the score. "But where I come from we don't need any painful suit echoes, or whatever you call them, to tell us to hold on to the king of clubs until the thirteenth trick."

Re-Entries

ONE of the first matters to demand the declarer's attention, the moment dummy's cards are laid down, is the probability that he will have to provide for getting into dummy's hand twice. This double re-entry may be wanted for any one of several purposes. If one has an ace-queen-jack suit, or an ace-jack-ten finesse, two leads from the weaker hand must be planned for. They may not both be needed, but they must be available.

It is frequently necessary to put dummy in twice in order to make a long suit. Perhaps the first re-entry will be necessary to clear the suit, the second to bring it into play. Again, there may be an opportunity to lead through the right-hand opponent twice, to ruff out a suit, or to establish an inferior card.

All such situations as require two reentries must be planned for in advance, end the opportunity to take them is frequently lost on the very first trick, through being too hasty in playing to it. A familiar example, given in most of the books, is a small card led through queen and jack alone in dummy, aceking and one small in the declarer's hand. A re-entry may be made by overtaking the jack with the king.

All such situations are governed by the general rule that if the declarer and dummy hold between them four honors in sequence in any suit, it is usually possible for either hand to get into the lead twice. All that is necessary is for the player to know the mechanical rule under which this is

done, and apply it. An example!

The declaration is no-trump, by 4 and A leads the spades, the first trick being won by the queen. The problem is to get dummy into the lead twice, so as to get the benefit of the double finesse in clubs, as there is nothing else in the hand worth thinking about.

Having four honors in sequence between the two hands, in the diamond suit, the rule is to lead the queen or jack and overtake it with the king. This is the first re-entry. The club finesse loses to the king and A establishes the spades. The next step is to see if either adversary is void of diamonds, because if both follow suit to the ace, the dummy's five of diamonds becomes a re-entry for the second finesse in clubs on the fourth round of the diamond suit. This wins the game, before the spades get in again. The original lead of the small diamond will not do this.

This rule, at two re-entreis Can be made in any suit in which declarer and dummy hold between them four honors in sequence, will usually hold true in suits that do not contain the ace, but the management of the re-entries differs materially. Here is a good example:

Z is playing a no-trumper, and the opening lead is the spade queen, which he wins with the ace or king. The problem before him is not only to get out of the way of the long diamond suit in the dummy, but to get dummy in twice; once to clear the suit, and once to make it.

Having four honors in one suit, hearts, between the two hands, two reentries are an easy matter, but allowance must be made for the fact that one of these re-entries can be killed by whichever opponent holds the ace. As they have the choice as to which of the tricks they will kill, it will be necessary to put dummy in three times to make two re-entries, because one will be killed by the ace.

This is accomplished, after getting rid of the ace of diamonds, by leading the jack of hearts and overtaking it with the queen; just as the king overtook the queen or jack in the first example, B may allow this trick to hold, to sec what is going to happen. The diamonds are then led until the king falls, Z discarding spades. Whatever B leads, Z gets into the lead again, probably on the spade, if he false-carded the ace on the first trick.

Now the nine of hearts must be led, and dummy must overtake it with the ten. If B does not take this trick, all the diamonds make. Another spade, and A makes two in that suit, but that ends it, as the trey of hearts will bring in the long diamonds and win the game.

Answer to the April Problem

THIS was the distribution of the cards in Problem XII, by Frank Roy.

There are no trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want all eight tricks against any defence. This is how they do it. Z leads the ten of hearts, which A covers and Y wins, B discarding a club. Y returns the eight of hearts, and B discards a spade, while Z sheds a club. Y's next lead is a club, which B covers with the jack and Z wins with the ace. On this trick, A can discard either the spade or the diamond,

Z leads the suit B has discarded, the spade ten, which A must cover and Y wins. When Y returns the spade, the eight in Z's hand is good, and B must discard a diamond, or Z makes all the dubs. When Z leads the ten of diamonds, A must pass it up, to block Y, but Z can put Y in with the smaller of his remaining clubs, so that Y shall make the last trick with the eight of diamonds.

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now