Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAppraising the Assisting Bid

Simple Rules by Which the Bidder's Partner Decides Whether or Not to Assist

R. F. FOSTER

THERE is probably no part of the tactics of auction bridge in which the average run of partners is so unreliable as in the matter of assists. This is probably because most players overlook, or their attention has never been called to, two important factors in their estimate of the strength or weakness of their hands, when they are called upon to assist or not to assist their partners' original bids. That is, free bids made by the dealer, or by second hand when the dealer passes. For the sake of clarity, we shall suppose the dealer is always the bidder.

The first and most important consideration is that at least three of the prospective tricks in the partner's hand, if he has so many, are included in the dealer's bid. The second consideration, and almost as important as the first, is the exact value of their trump holdings, which is something the average player is continually overestimating.

It is generally conceded by good players that if the dealer has as good as ace and king at the top of a five-card major suit, he has a sound original bid, regardless of the rest of his hand. Let us suppose this suit to be hearts. Experience and calculation have agreed in showing that such a trump suit will be good for four tricks on the average. This does not mean that it will win four trump tricks every time the bid is left in, but that it will produce 400 tricks in 100 trials, if the opening bid is one heart and the hand is played with hearts for trumps.

But the dealer who bids a heart on four tricks undertakes to win seven, not four, and he will undertake to do this, even if he has nothing in his hand but those five hearts to the ace-king. That is his contract, to win seven tricks with hearts trumps. It is quite true that his hand may be much stronger than that, but his original bid of one heart does not say so. That will be shown when he rebids his hand, if he is overcallcd.

IF the second hand passes, the dealer's partner is not called upon to say anything unless he is so short in hearts that he must or should deny the dealer's suit, but that part of the game is not at present under discussion. If the second hand overcalls the dealer's heart bid, let us say with a spade, the dealer's partner may have two good reasons for refusing to assist the hearts. He may not have more than normal strength in the heart suit itself, which would be three small cards; or two, one of them as good as the queen. Or, he may not have more than the three tricks that were included in the dealer's bid when he undertook to make seven with only four in his hand.

Taking the normal assistance in the heart suit for granted, there are three elements that constitute assisting strength in the partner's hand. The first is high cards in other suits. The second is the ability to ruff the first or second round of a suit. The third is the number of trumps more than normal, which make it probable that the declarer will not lose a single trick in trumps if he holds five to the ace-king.

The high cards, aces and kings, or such combinations of honours as are given a standard average value, are counted on the assumption that the hand is going to be played at hearts. The only change in these values is when the suit in which any of these high cards are held is bid by an adversary or by the dealer. In such cases the ace falls to its face value, one trick, and if it is the trump suit it counts nothing except as an extra trump if there are three of them, or more.

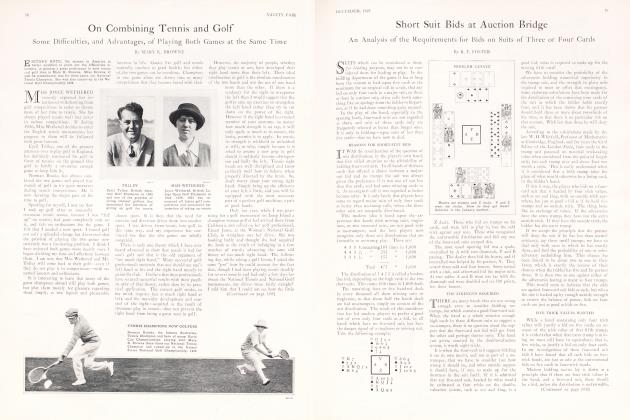

PROBLEM LXXXIX

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want seven tricks. How do they get them? Solution in the December number

One of the most common and persistent errors in the average player's assisting is attaching too great a value to length in trumps, regardless of what can be done with them. Taking three small trumps as normal, they are worth nothing in counting up the assisting value of the hand, because the dealer expects you to have them and they are therefore included in his bid. Four or five trumps add only one trick to the assisting value of the hand, and this value is due to the probability that, with so many between the two hands, the declarer will not lose a trick in trumps.

One of the important values in an assisting, or dummy, hand, is the ability to trump the first or second round of a suit, or both. By putting a trump alongside a singleton, one may count that trump as equal to the king of that suit. Putting two trumps where there is a missing suit, one may count it as equal to three tricks in the play of the hand.

Take the following examples of third hands on dealer's bids:

If the dealer bids a heart, second hand a spade, neither of these hands is good enough for a sound assist, for two reasons. The trump holding in each case is only normal, with no ability to trump any suit until the third round; and neither hand contains more than the three tricks that are included in the dealer's bid. If he has only four tricks himself, but has undertaken to win seven, you are carrying him beyond his depth if you force him to win-eight.

If we change these hands a little we might get this distribution:

In C, we find a four-trick valuation, counting the club ace as worth 2, no one having bid that suit; the king of diamonds as 1, and the ability to trump the second round of spades as equal to the king of that suit, worth 1; total 4, which is a trick more than the dealer expects. If he has 4, to which you add 4, the total is eight, equal to a bid of two hearts.

In D, the ace is worth 2 tricks, and the ability to trump both first and second rounds of a suit 3 more, bringing the value of the assist up to 5, which is good for two assists.

IT should be noted that whether the suit that can be trumped is the suit bid against the dealer or another suit, docs not matter. It should also be remembered that any extra length in trumps should not be counted twice over. If the trump is counted on for ruffing, it niust not also be counted on for length only. Take these two hands as examples, dealer bidding a heart and the second hand a spade.

In E, we count the ace as worth 2, the king 1, and the extra trump 1. These 4 tricks are an assist. The reason for counting the extra trump is that if the declarer holds five to the ace-king he may win five tricks in trumps.

The reason that F is no better than E is that nothing can be done with the extra trump, and all five of them will probably fall on the five held by the declarer, the prospect of trumping a third round being too remote to justify bidding on it.

If the dealer is overcalled, and the third hand passes without assisting, and has no suit good enough to justify a shift, it is often found that the dealer is quite strong enough to rebid his hand. This invariably shows that he holds one or more sure tricks in some suit or suits, other than the one named in his bid. On some occasions he may have a two-suiter and bid them both.

When a two-suiter is shown, the question of strength for an assist is secondary, and the important thing is to indicate which of the two suits can be the better supported. In other words, the partner is called upon to choose; not to assist.

(Continued on page 108)

(Continued from fage 89)

Suppose the dealer bids a heart, second hand a spade and third hand holds any such combination of values as is shown in A or B examples, he would be justified in assisting on the second round, although not on the first, if the dealer rebid the hearts and the second hand went to two spades. If the dealer has 6 values for his rebid, and his partner has 3, that is 9, equal to three odd in hearts. The dealer will know that his partner has exactly 3 tricks, because with 4 he would have assisted the first time, and with less than 3 he would not assist the second time.

It must not be imagined that, just because a hand is not worth an assist, or should not assist more than once, such bids should never be made. Every good player will occasionally overbid a hand, but the point to be kept in view is that he should know just how much he is overbidding and how much risk he is running of being doubled and set. That part of the game belongs to what is called "poker bridge" and "push-em-up", both of which are great favourites with a certain class of players.

Here is a deal which shows several of the points connected with assisting bids:

The Partner

The Dealer

The dealer bid a spade, the higher ranking of two suits, each of which is worth 3 tricks, total 6, worth a rebid. Second hand bids two clubs. The dealer's partner passes, as his ace of clubs falls to its face value as soon as an adversary bids that suit, and his hand is worth 2 only, the ace and the extra trump, as king and one small would be normal.

Instead of rebidding the spades, which he might do, the dealer tries the diamonds, and second hand goes to three clubs. Now the dealer's partner cares nothing about his strength but indicates his preference for the spades by bidding three.

It is a game hand in spades if the dealer sees the importance of getting two finesses in diamonds by letting the trumps alone and taking the first finesse on winning with the club ace; and, on getting in again, leading high trumps from his own hand, dummy winning the third round and giving him the second diamond finesse.

ANSWER TO THE OCTOBER PROBLEM

This was the distribution in Problem LXXXVIII:

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want seven tricks. This is how they get them:

Z leads ace and another club, A winning the second round with the jack, as nothing can be gained by B's trumping the trick.

If A leads a diamond, Y passes it up, allowing Z to trump it and come through A's minor tenace in trumps, so that Y can pick up both of them and make the rest of the tricks.

If A leads a spade, Y wins with the ace, and leads a small diamond for Z to trump, and again Z can lead trumps through A.

If A leads the trump, Y wins whichever trump A plays, and leads the small diamond for Z to trump, getting in with the ace of spades to pull the trumps and make the third club.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now