Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowNew Theories of Doubling In Auction Bridge

Simple Rules for Reading the Meaning of the Modern Double

R. F. FOSTER

MRS. CHATWELL and her daughter Gertrude had not been at the fashionable hotel in the mountains more than three days, before everyone who came within sound of the mother's voice was aware that Gertrude was the most wonderful girl in the world. The girl herself, however, was conscious of some of her shortcomings, and when Mr. Gettem, who had a great reputation as a bridge player, suggested that he would like to have a rubber with her some evening she felt it incumbent on her to study up. She knew that bridge was one of the things in which beauty does not count.

The first thing she did was to buy two or three books on the game, but, after reading them assiduously, she felt she must have a lesson. She therefore called in the services of an elderly lady whose friends handed out their charity to her in the form of fees for bridge lessons. This teacher impressed upon Gertrude that, with a good partner, who would do most of the playing, there remained but three rules to which she need pay attention; these were carefully written down and committed to memory:

Always show your partner what you have. Play high-low with only two of his suit. Play high cards from the hand that is short in a suit.

Having these three simple rules firmly fixed in her mind, Gertrude confided to Mr. Gettem that she was just crazy to have a rubber. Having been previously assured by the mother that Gertrude was a prodigy at cards, he arranged a rubber with Mr. and Mrs. Bidwell, a married couple whom he considered easy picking, notifying his partner in advance that they were "wild bidders, and would double anything." On sitting down, the only mention of points was a hasty agreement to play for the "usual stake," which Gertrude supposed to be about half a cent, whereas it was actually ten cents a point. It did not matter, anyway. Mr. Gettem was such a wonderful player, and she had those three rules pat, so she could not lose much money.

Things went smoothly enough at first, with no call on her to do anything, until they were each a game, and the Bid wells were 10 up on the rubber game. This was the distribution of the cards at that particular juncture:

Mrs. Bidwell dealt and bid no-trump, which Mr. Gettem passed, hoping the bid would hold, and seeing no hope of game in clubs. Mr. Bidwell called the hearts, and Gertrude, mindful of her lesson and the importance of showing her partner what she had, went two spades, which Mrs. Bidwell at once overcalled with two no-trumps. Mr. Gettem doubled, and all passed.

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want four tricks against any defence. How do they get them? Solution in the December number.

There are several lines of defence in this problem, but they can all be met by correct play.

The opening lead was the king of clubs, on which Gertrude, proud of her memory of her lesson, played the eight. On the queen of clubs she dropped the deuce. After thinking the situation over for a moment, and wondering if he could trust his partner to unblock, he concluded it safer to lead the small club to her jack and nine, as she was showing four by her echo, in a no-trump hand. As the dealer would not follow suit, the continuation would be obvious. That was the last he saw of a trick until the declarer had put dummy in with the jack of diamonds, made two hearts and run down five more diamonds. Three odd doubled, and the rubber, 410 points.

"Why do you echo in clubs, partner?" asked Mr. Gettem, as mildly as his annoyance would allow.

"Teacher told me always to play high-low with only two of my partner's suit," she explained, looking troubled.

"But that is only against a trump contract. High-low at no-trumps means four of the suit. If you play the deuce the first time, I know you have not four and put you in with a spade tp come through, in case you have only two clubs. That sets the contract for 300, aces easy."

"That's only seventy dollars difference. Forget it," suggested Mr. Bid^well. "Let us cut for the first deal. New rubber."

Mr. Gettem got the deal, and went game. On the next deal he made 18 points, and then Gertrude dealt, rather absent-mindedly, as she was still worrying about the flaw in her rules. This was the distribution:

At least one rule had always worked pretty well so far—"Always show your partner what you have"; so, as it was her first say, Gertrude bid a heart. Mrs. Bidwell called the diamonds, and Mr. Gettem promptly helped the hearts, Mr. Bidwell going to two spades, Mr. Gettem to three hearts; upon which, Mr. Bidwell remarked that it was a free double and everyone passed.

Mrs. Bidwell led three rounds of diamonds, her partner playing the eight and deuce, winning the third round with the queen, at which Gertrude looked up quickly. On that disastrous hand she had played high-low with the eight and deuce. Now, here was a supposedly first-class player doing it with three cards. She trumped and led trumps, winning the third and last trump with the king.

There was one more rule which she had not had any opportunity to try as yet, "Play the high cards from the hand that is short in the suit." Dummy was short in spades; so she led the deuce of spades and put on the ace. Then she led a club, intending to put on the high card in her own hand; but before she got a chance Mr. Bidwell had taken home four spade tricks, setting the contract for 300, less five honours.

"Remarkable opening bid of yours, partner," observed Mr. Gettem; "but you go game if you set up the clubs after pulling all the trumps, as he has no diamond left to lead. Three hearts doubled and the honours, means the rubber; 388 points, instead of losing 300."

"Only another seventy dollars. Forget it," admonished Mr. Bidwell, cheerily.

"I am very sorry, partner," Gertrude whimpered, almost in tears. "I am sure I followed the rules my teacher gave me."

"A little learning is a dangerous thing," quoted Mr. Gettem. "Drink deep, or taste not of the Pierian spring."

Positive and Negative Doubling

BRIDGE players are indebted to Mr. A. A. Anderson, Vice-President of the Knickerbocker Whist Club of New York, for the suggestion to substitute the terms "negative" and "positive," when speaking of the modern double, instead of the older forms, "conventional" and "business". The negative double denies the suit doubled; the positive double indicates ability to defeat the contract.

Probably the most lucid and satisfactory explanation, so far given, as to the uses and limitations of the modern double, especially in its negative uses, has been given to us in Wilbur C. Whitehead's Auction Bridge Standards, about forty pages being devoted to it. He lays down three simple rules for the guidance of those who are not thoroughly familiar with the uses of the double, which should enable any person to distinguish clearly between the negative and positive at any stage of the bidding.

Continued on page 84

Continued from page 69

1. The negative double must be made before the doubler's partner has declared himself in any way.

2. It must be made at the first opportunity.

3. It must be a double of not more than one no-trump, or not more than three in suit.

As distinguished from the negative double, which is a demand for the partner to declare himself, the positive dou-

ble, which aims at letting the adversaries play the hand and penalizing them, is any double after the doubler's partner has declared himself, either by bidding or doubling, or any double which was not made at the first opportunity.

It is a common error to suppose that the negative double is a command to the partner to declare himself which must be answered. The partner's silence may

be an answer; if, in his judgment, there is no hope of going game, and the contract is manifestly impossible for the

adversaries. In such cases the double is much better left in. Many players recognize the value of this latitude in answer to the positive double, and are quick to take it out when they think there is more likelihood of gain by playing the hand than by taking penalties.

The many variations in the circumstances under which the negative double has to be carefully distinguished from the positive, frequently prove confusing to the average player. Here are a few examples, which may make matters clear, as a thorough understanding of this convention has become a necessary part of the equipment of any one with pretensions to playing good auction.

1. Dealer bids a heart. Second hand doubles. This is negative, because the doubler's partner has not yet declared

2. Dealer bids a heart, second hand a spade. Third and fourth hands pass. a spade. Thrid and fourth hands pass. Dealer goes two hearts and second hand doubles. This is positive. Although the doubler's partner has said nothing so far, the double was not made at the first opportunity.

3. Dealer bids a heart, second hand doubles, third hand says two hearts, doubles, third hand says two hearts fourth hand and dealer passing. If second hand doubles two hearts, that is still negative, because the doublers partner has not declared himself, and hearts were doubled at the first opportunity.

4. Dealer bids a heart, second hand doubles, third hand says two hearts and fourth hand doubles two hearts. This is positive, because the partner has already declared himself by doubling one heart.

5. Dealer bids no-trump, fourth hand two spades, which the dealer doubles. This is negative.

6. Dealer bids no-trump, second hand passes, third hand says two no-trumps, and fourth hand doubles. This is positive, because it is a bid of more than one no-trumps.

7. Dealer bids no-trump, second and third hands pass, and fourth hand doubles. This is negative. If dealer or his partner goes to two no-trumps and fourth hand doubles again, this is positive, as it is more than one no-trump; but if dealer or his partner shifts two in a suit and fourth hand doubles, that is still negative, and asks partner to bid.

8. Dealer bids no-trump, fourth hand two spades, dealer three diamonds, second hand three spades, third and fourth hands passing. The dealer doubles three spades. This is positive, as the double of the spades was not made at the first opportunity,

9. An unusual case would be this: Dealer bids a diamond, second hand doubles, third hand bids two diamonds, fourth hand and dealer pass. Second hand now bids two spades, third hand three diamonds, fourth hand and dealer passing. Second hand doubles. This is still a negative double, because he doubled the diamonds at the first opportunity, and his partner has not said a word so far. The last double practically says, "If you cannot help the spades, what have you got?"

Players are frequently blamed for leaving negative doubles in, with a resulting loss, when the real fault lies with the doubler, whose hand did not justify the declaration. The strength necessary for a negative double of suit or no-trump is five or six tricks, counted according to modern schedules. The only excuse for doubling on weaker hands is the ability to support either of the major suits. As a rule, it is bad policy to double no-trumpers unless able to support either major suit or to go to two no-trumps in case the partner calls the major suit in which the doubler is weak.

One of the less understood uses of the double, as pointed out by Mr. Whitehead, is to show that there is strength in other suits than the one called. Whitehead gives this example:

In the actual play, Z starting with a spade~and A two hearts, they got it up to three spades, Y and B saying noth ing, until B doubled three spades and set the contract 318 points. -

When Y refused to assist the spades, over A's bid of two hearts, Z should have doubled. This would have prac tically said to~ Y, "I have bid spades, but I actually have a no-trumper, but for the weakness in hearts. If you have no spades, what have you got?" The result would have been a diamond con tract, and five odd and game against any. defence.

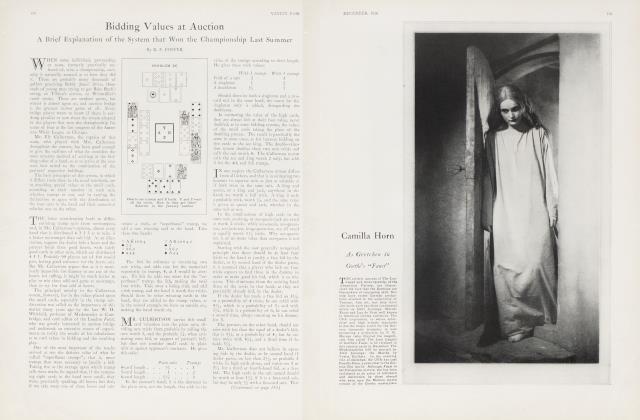

Answer to the October Problem

THIS was the distribution in Problem XXIX, given last month, which many readers of this magazine probably thought could not be solved.

There are no-trumps and it is Z's lead. Y and Z want seven tricks out of the eight. This is how they get them: Z leads the ace of hearts and Y discards a small diamond. Z follows with the queen of hearts, on which Y discards another diamond. What follows depends on what B has done up feo this point. If B has kept a smaller heart than A, the next lead from Z's hand must be the king of diamonds, which Y ducks, and on which B will discard his third heart.

Continued on page 96

Continued from page 84

Z now leads the spade king, on which

Y sheds a small club, B a small spade. This clears the field for Z to throw A into the lead with the small heart, while

Y discards another diamond, B a spade. Now, if A leads the diamond, he forces his partner, B, to discard his last spade or unguard the clubs. If A prefers to lead the club, he kills his partner's queen.

B may decide to keep the best heart if he plays the ten or jack to the first round and the other high heart on the queen. To meet this defence, Z goes right on with the third heart, giving B the trick, while Y discards a third diamond. It is now B's choice of defences.

If B leads the spade, Z makes two tricks in that suit at once, and Y trims his discard according to the pattern set by A, who discards first. Suppose A discards a diamond, Y can overtake Z's king of diamonds with the ace and make a trick with the nine. If A prefers to discard a club, Y will blank his ace of diamonds, win Z's king of diamonds on the next trick and lead the club ten through B's queen.

The third defence for B, at the fourth trick, is to lead the queen of clubs. This Z wins with the king, and makes the trick with his king of spades, on which Y discards another diamond. Now Y still has the ace of diamonds, to get in with, and two good clubs.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now