Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOur Auction Bridge Refuge

A Sanctuary and Retreat for Persistent—Not to Say Incurable—Bridge Addicts

R. F. FOSTER

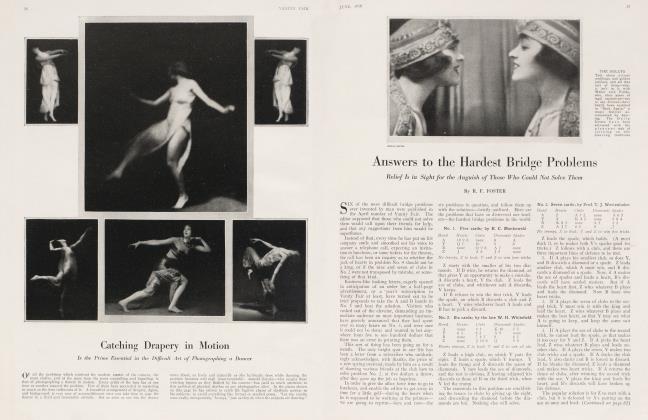

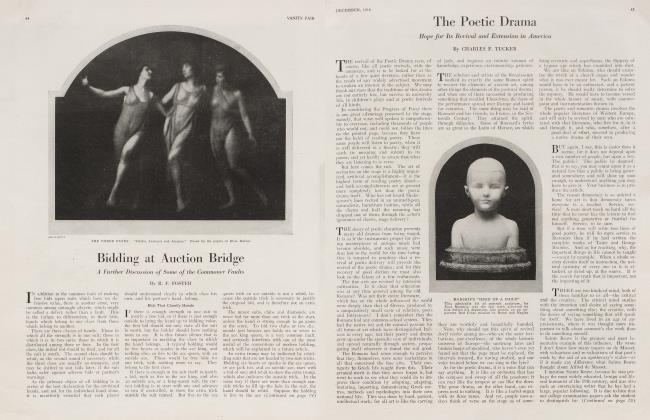

There are no trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want five tricks. How do they get them? Solution in the May number.

IN SOCIAL bridge parties, arranged for two tables, it sometimes unfortunately happens that at the last moment one of the eight invited cannot come, or is delayed, and all efforts to get a substitute are fruitless. The usual result is that the evening is spoilt, as three people have to sit and look on at every alternate rubber, or six make up a table and the seventh gets no bridge at all.

Heretofore this difficulty has been foreseen and provided against by the simple plan of inviting nine -people for a two-table game. There is a women's club in New York which is limited to nine players at each meeting. Their plan is for one to sit out and to take the place of the highest cut at whichever table finishes the rubber first. The one who is cut out at that table gets in at the other table, as soon as that rubber is finished. If one player fails to come, there are two full tables.

Mr. W. O. Preston has evolved a scheme which makes it possible to keep two rubbers going, even if there are only seven players available. This is accomplished by the simple process of loaning the dummy at the full table to make up the four at the other table, so that there .may be no change in the usual process of bidding; two players against two.

The ingenious part of the Preston system lies in the method of scoring. The fundamental idea is that the original arrangement at each of the two tables is placed at the top of the score-card, and that the original partners win or lose the result of the rubber, whether they play all the hands themselves, or a substitute plays some of them for them; the substitution being due to the borrowing of players from one table to the other. The moment the bidding is complete at either table, and dummy's cards are laid down, the dummy himself is free to make up the other table; but must stay there until he becomes a dummy again.

IF WE suppose seven players to cut for the choice of seats, cards, and the deal at the first table, the four lowest start there. Let us further suppose, for the sake of this description, that these four are A and B, cutting as partners against C and D. At the other table, three players cut for choice of seats and cards and the first deal in the same way. Let us say that G gets the deal, E and F being his opponents, the seat opposite G being left vacant until the arrival of the dummy at table No. 1. G can proceed to deal the cards into four packets, as usual, and all is ready to begin.

This gives us this arrangement:

At table No. 1, let us suppose that D becomes the declarer, and makes 30 and 30. The moment the bidding is closed, his dummy, C, goes to table No. 2 and takes the vacant seat, opposite G. The partnerships are then entered at the top of that score-pad as E and F against G and C. No matter who moves, he must belong to two tables, with a chance to win—or lose—at both. At this table, suppose E gets the contract and scores 36 and 36. His dummy, F, is free to go to Table No. 1 as soon as wanted. This will bring him into the seat left vacant by C, and make him D's partner for the next deal.

At this table, No. 1, let us suppose A to become the declarer on the second game of the rubber, and to score 24 below, 16 above. His dummy, B, goes at once to table No. 2, so as to be ready to bid the second deal there as E's partner, taking the place left vacant by F. It will thus be seen that every time a player gets the contract, he loses his partner, who leaves the table as soon as he lays down dummy's cards. This continual change of partners makes the game more interesting to some players. Others do not like it. It was one of the minor objections to pirate bridge.

At table No. 2, suppose G gets the contract, and scores 36 below, 18 above. This sends his partner, C, back to table No. 1, taking his old position as D's partner. C niust not take the place just vacated by B, with A as his partner, instead of his opponent, or C would be playing against himself, as his financial interest in the rubber remains as D's partner, with whom he started. C and F, therefore, change places.

Here we shall suppose that F gets the contract, and scores 32 and 32, which is entered to the credit of A and B, as A has not left his seat, and is still playing with the same cards, red or blue, as the case may be. It is a good idea to put the colour of the packs at the top of the score-pad, as along about the fourth or fifth deal of a rubber neither of the original partners with that pack may be in those seats; but they get credit for whatever is won or lost with the red pack, if they started with it. This is one of the amusing features of the game. Sometimes one has two substitutes, instead of one, playing the hands.

As F is the declarer at table No. 1 on the third deal, he drives A to table No. 2, as G's partner. At this table A gets the contract, and makes a little slam in hearts, with four honors, winning the rubber for G and C, who started in that position. His partner, G, goes back to table No. 1, and plays with F as his partner, against C and D.

This is the fourth deal at this table, and G gets the play at five odd in diamonds, doubled, and makes it, with five honors. This gives the rubber to A and B, who started in that position at table No. 1, although neither of those players is at the table now. F goes to table No. 2 to make them up for the second rubber there, all four cutting for partners, seats and deal.

THE following scores, from actual play, show the various changes of position in the players from deal to deal, and the scores made, together with the colors of the packs used:

Each rubber is a four, throwing off the odd figures and taking the nearest hundred. The first player to move, C, who was interested in both rubbers, lost at one and won at the other. Three of the seven players, D, E and G, retained their seats throughout the rubbers in which they were interested.

It might be possible that two players who started as partners would find themselves opposed for several deals, as A and B are on the third deal at table No. 2; but as this can happen only at a table in which they have no interest in the result, because they do not belong to that table except as substitutes, there can be no objection to it.

Mr. Preston points out that there is a possibility of a player's being unlucky enough not to be in the scoring at all after the first rubber. This is a very rare case, requiring a peculiar run of circumstances to bring it about. To illustrate : Suppose A and B start against C and D, and C moves, D winning a game. At the other table, E and F start the other rubber against G and C. On the next deal, B goes to table No. 2, and stays there for three deals. On the second of these, table No. 1 finishes its rubber and on the third starts another, with A and G against F and D. When B comes to that table, he is not interested in that rubber, and they finish the rubber at table No. 2 after B leaves.

Continued on page 84

Continued from page 67

At table No. 2, they start a-fresh rubber by getting F from table No. 1, so that B is not interested in either rubber, not having been at the table at which either of the rubbers was started. Both F and D are in both rubbers. This objection is largely on paper, and if it happened now and then, it would be equalized by the times a player would be in both rubbers.

Waiting for a Fourth

WHEN three bridge players are waiting for a fourth to turn up, the usual alternatives are to start a rubber of three-hand, or to play rummy. In either selection, if the available fourth suddenly turns up, he has to wait for the conclusion of the threehand rubber, or the decision of the rummy game.

It has been suggested by a wellknown bridge expert that as the desirable thing is to be ready for the fourth man the moment he appears, all that is necessary is to alter th? method of scoring at three hand, so that every deal ends the rubber. The rubber at bridge being no longer two games out ot three, but the greater number of points won (see the latest edition of the laws of auction), rubber may end at anv time the points are added up.

Answer to the March Problem

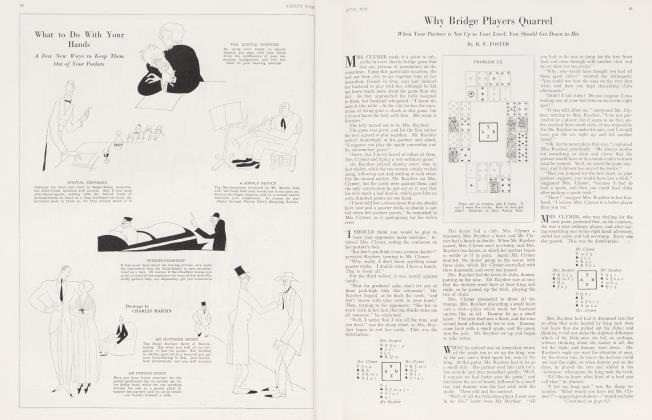

THIS was the distribution in problem XXII, one of Captain Frank Roy's compositions:

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want six tricks. This is how they get them:

Z leads the ace of spades, and follows with the trump, on which Y plays the ace, winning A's nine and dropping the jack from B's hand. Two winning spades follow. If A trumps the second spade, he must lead clubs up to Z, who makes both eight and jack, Y making the last trick with the trump.

If A refuses to trump the spade, he must discard a card, leaving himself with two only. In that case Y follows the last winning spade with the losing trump, putting A in, and again Z must make two club tricks.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now