Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThere Isn't Any Santa Claus

Plays of the New Season Seem Willing to Face the Fact that Everything Is Not Always for the Best

HEYWOOD BROUN

ON account of the business depression, or something, playwrights have decided that they need not refrain from letting theatregoers in on the secret that everything which happens is not necessarily for the best. Indeed the most daring of the dramatists have been bold enough to hint at times that there isn't any Santa Claus. Of the notable plays of recent weeks two are definitely tragedies, while a third is a comedy so bitter that the laughter hurts. In addition The Easiest Way, the father of all modern American tragedy, has been revived.

Personally we would like Daddy's Gone AHunting of Zoe Akins a little better if it ended happily. The tragic ending this time represents no brave unwillingness to compromise, but rather a shortcut of a playwright not quite prepared to work out her interesting theme for all its possibilities. It has been much easier to let the heroine say, "God knows" and bring down the curtain. But Miss Akins ought, also, to know. The playwright is herself a creator, and from her the full and conventional six days of work may be demanded.

As a god, the dramatist ought to fulfill the obligations of divinity. She should not begin to rest on the fourth day or, worse still, the third. Daddy's Gone A-Hunting is an unfinished play. To us it seems a fine one, but we think that it is a prologue to one still greater.

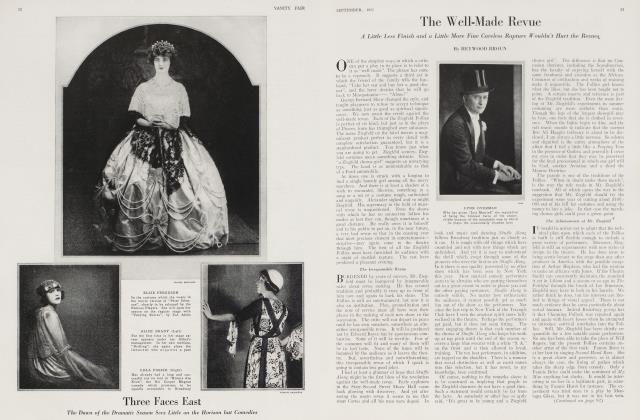

The first act is the best work which Miss Akins has done. Indeed it is an act fine enough to stand on the credit side of any master's ledger. After that there is a diminution in skill. The emphasis of the play must fall on the role of the heroine, particularly since Miss Marjorie Rambeau gives a superb performance in the role. Accordingly, one is led to expect a story of the growth and development of this woman or of downfall and decay. Instead she stands still. In the playwright's mind she seems to be an interesting, but rather slow and immature woman. We find her at the beginning of the play waiting for the return of her husband who has spent a year in Paris studying art. She waits for him eagerly, only to meet the most poignant disappointment. He returns an utterly strange person. The life he once lived no longer interests him. He is searching for something so intangible that he must journey after it alone. Husband and wife continue to keep up a pretense of marriage, but the wife is constantly harried not only by her husband's lack of love, but by his sudden forays in other directions for romantic adventure.

The Burden of Freedom

AND yet when one of the women, concerned in an escapade comes and pleads with the wife not to take action for a divorce she agrees readily enough. She goes further. In a puzzled and hesitant way she says that she is beginning to see that there is something to be said for freedom, after all. In spite of the terrific hardships it has imposed upon her she has a glimmer that being free in marriage has a dignity as well as a glamour. Perhaps, we jumped at a false clue too eagerly, for we were prepared from then on to find Miss Akins writing a story about the growth of a woman. As a matter of fact, nothing of the sort happened. The wife began to wonder whether or not her husband meant what he said when he told her that freedom included both of them. She tested him. She dangled bracelets in front of him, and then to her horror discovered that he had been telling the truth. She too was free and she could not bear it. Indeed she left her home on the instant and dashed into the protection of a man who had always loved her.

She found life outside of marriage more conventionally satisfying than existence with a husband who refused to be jealous. But after five years the artist and his wife meet again. Their child is ill—we forgot to mention the child, but she had been around for all that from the beginning of the play. The child dies and in a sudden burst of sympathy for her husband the woman realizes that he is the man she has loved all the time. She wants to return to him. She says goodbye to the lover, only to find that her husband no longer wants her. She has never had any great itch for the freedom, but in the end she is left the most free and lonely figure of the lot.

This is unquestionably tragic, but it is the tragedy of a person who is merely buffeted about. The heroine is never turned back by fate because she is not going any place in particular. Hers is the tragedy of a dead leaf or a bit of paper in the wind. Things with fight in them are finer. Again the tragic end swings largely on the death of the child, which is merely a sudden unmotivated turn of fortune. Nevertheless, Daddy's Gone A-Hunting is well worth your attention. The first act is almost a model of what every play ought to be and, thereafter, although the main current may abate somewhat, the play is gripping, taken scene by scene. Throughout Miss Akins has written with simplicity and with feeling and Marjorie Rambeau has never appeared to better advantage than in the principal part. She is exactly the type with which Arthur Hopkins should work. Left to herself Miss Rambeau will rant and get her feet upon the mountains. Put through the Hopkins school of repression, everything comes out quite right. One feels always that the player has something in reserve, and yet the original exuberance of the actress is such that the Hopkins wringer has not left her dry and crackling. There is some fine work in the play also by Lee Baker. One or two extraordinary moments are contributed by Frank Conroy, but somehow or other, we can never get over our prejudice in favour of actors whom we can hear.

"The Detour"

FINER than Daddy Goes A-Hunting and in fact as capital a piece of tragic writing as the American theatre has known is The Detour, by Owen Davis. He was a king in melodrama, but he has approached his present job with all the simplicity of a commoner. Instead of tuning his ear for phrases with an echo, he has been content to set down language as people speak it. For us the story fulfills every requirement of tragedy. Nobody dies, nobody is hanged, nobody goes mad. The play ends much as it has begun. People live on. Those who dreamed still dream, in spite of crushing disappointments which have come upon them, and to our mind the most poignant thing in tragedy is that visions do persist after hope has gone.

The Detour concerns the wife of a Long Island farmer who has always wanted to get away from the land. She plans that her daughter shall be a great painter and skimps and saves with this end in view. Her plan brings her to the edge of a break with her husband, but just at the moment she and her daughter are setting out for New York, a neighbouring artist makes the revelation that the girl has no talent whatsoever. Inwardly, the girl's disappointment is not terrific. Her ambition had always been something imposed upon her by her mother's will. She decides to marry the man next door and the money saved up for her artistic education goes to buy a smart piece of meadow land. The mother has to face her tragedy alone and at the end we find her dropping some new coins into the old jar. She thinks that perhaps the grandchild will be her proxy in the world beyond the farm.

The theme is, of course, not startling in freshness, but it is amply novel to serve its place in the theatre. It is a theme which has the advantage of assuming at times the stature of a story dealing with all men and all women. Naturally, many of us face quite a different problem. We are trying to get away from the dull routine and grind of city life and longing to become adventurous farmers. Nevertheless the implications of the plot which Mr. Davis has used reach out far enough to nudge us all, even those in chimney corners. There are one or two places in which the early profligacy of Mr. Davis in cheap melodrama returns to plague him. These old sins crop out in an occasional tendency of characters to talk in language a little more flowery than life sanctions. There are also a few moments in which Mr. Davis boldly steps in and, thrusting the characters aside, inserts a funny line, or, to speak more strictly, a gag; but these are exceptional. The Detour is for the most part strikingly simple and sincere. It has a strong and sweeping current and it approaches great tragedy in its scrupulous care that nothing shall come in suddenly by the door of chance or accident.

Continued on page 100

Continued from page 33

More than that, it is a tragedy in which justice is done. Broadly speaking, men suffer for their sins rather than their virtues. Job, for instance, seems less a tragic figure than a gentleman out of luck. Although our hearts bleed readily enough for the heroine presented by Mr. Davis, we have no difficulty in realizing that her dream deserved to fail, since this career which obsessed her was something she planned to thrust ready made upon another. She is defeated because, in spite of new fangled notions, she clung to the old one which makes a mother the eternal manager of the affairs of her children.

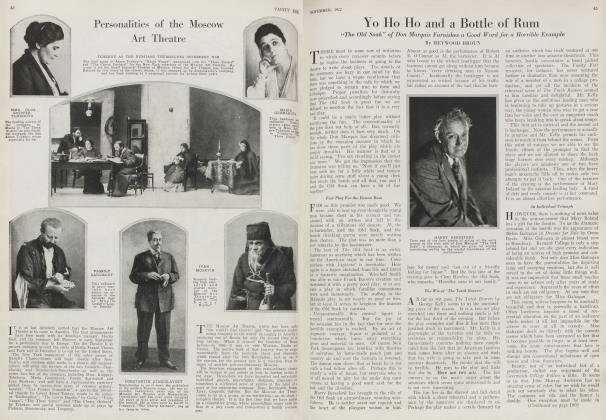

Effie Shannon has brought fine fervour to the role of the mother and she and Augustin Duncan, who staged the piece, make it throughout one of the great achievements of our theatre.

The Cynical Maugham

T'HE third distinguished offering of the early season is an importation. Somerset Maugham's The Circle is a comedy, but it need not be excluded from the evidence which we are assembling to prove that the happy ending is no longer a universal demand. With all its cleverness, The Circle is so bitter in spirit that one laughs almost until his heart breaks. The play serves to bring back to the theatre an echo of such ancient dramatists as Pinero and Jones. The wife and the young man from Mesopotamia are with us again, although this time he comes from the Federated Malay States.

Everybody who has followed the English theatre knows the scene in which somebody tells the wife who wants to run away what a rotten time she will have wandering about cheap watering places without a marriage certificate. This speech used to be done by the friend of the family. He is the gentleman who was wont to wind up by telling the husband to "take her out and buy her a good dinner". Maugham is much smarter than that. He gives the speech to a lady who herself has done the wandering. Thirty years before the beginning of our play, Lady Kitty left her husband, Clive Champion-Cheney, and ran away with Lord Porteous. An old woman, she brings her mildewed romance back to England and finds that her son's wife is about to leave him. By unconscious example and direct precept, both the broken rebels against the herd warn the young couple not to repeat their error. The play seems about to end with one of those patched up endings, more moral than happy, according to the old formula, when Maugham suddenly steps in and turns everything with a puff of fresh air. The young man is his instrument. He takes the scene in hand by telling the girl that he never promised her happiness or anything like that. He had been talking about love and before the audience can say "Bernard Shaw" the two adventurers are away on their adventure, while the old couple, who made a mess of theirs, stand waving them Godspeed.

This may seem a little sentimental, but Maugham disarms such objection with great skill. He is so bitter for the better part of three acts that the sudden note of feeling catches everybody unawares and bowls him over before he can get his hands up to defend himself.

The twist at the end puts The Circle a good many notches up in our estimation, although it would still be a brilliant exercise in an old theatrical form without this spurt. In the very first act there is a single line which practically justifies the entire evening. Lord Porteous, returning to England, meets the son of the woman with whom he ran away. He gulps once and then says, "How do you do—I knew your father".

The role of Porteous falls to John Drew, who not only does well with it, but gives the lie to the old assertion that John Drew is always John Drew. Leslie Carter is also surprisingly good. She was never noted for her skill in comedy, but now she does it excellently, even though there is an occasional tendency to hammer points. However, the best performance of the evening seems to us to be that of Ernest Lawford, who plays the malicious old Clive Champion-Cheney. He makes his rapier work as gentle as plain mending and much more effective.

We know nothing else among the new offerings which stands on the same plane with the plays which have been mentioned. Still, Six Cylinder Love is capital entertainment. Half of it is the most familiar sort of theatrical trickery, but the other half which concerns misadventures with an automobile is fascinatingly new and amusing. However, nothing in the play is as good >as Ernest Truex, who gives a comedy performance worthy of a masterpiece. The Nightcap also seems to us excellent entertainment. It derives pretty frankly from The Bat, but the method employed by Guy Bolton and Max Marcin is quite different. They make no attempt to create an atmosphere of horror, but spend all their energies in farce. Before the evening is over they have fully convinced you that nothing is quite as funny as a good bank robbery, unless it is a bloody murder. Two Blocks Away presents Barney Bernard, one of our best character actors, but the play is only fitfully amusing. Swords, by Sidney Howard, is magnificently mounted by Robert Edmond Jones, but its verse seems bombastic to us, and its dramatic interest thin. The most striking performer in Tarzan of the Apes is a real lion. Unfortunately he is miscast. At any rate he deserves a better play.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now