Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Decagon of the Modern Double

The Original Janus of the Conventional Double Now Has Ten Faces

R. F. FOSTER

DOUBLING, as a convention, has become so much a part of the game in this country that it is incumbent upon anyone having any pretensions to being a bridge player to understand it in all ten of its varieties. Six of these variations are in common use; the others not being so well understood as yet.

The English writers on the game are unanimous in their condemnation of the conventional double. Dalton, in his 9th edition, just published, says only three conventions are allowed by good players: the call for a ruff; the call for a suit; and the echo (to show number at no-trump). He states that, "the difference between the English, or Simplicity School, is that it does not attempt to force its game on Americans; whereas the American, or Complex School, cannot rest without attempting to force its methods on England." He says, "the American likes to leave nothing to chance, and tries to reduce bridge to a sort of exact science, with his multiplicity of conventions, so as to leave as little as possible to individual intuition and intelligence." (Page 105.)

In a sense, multiplicity is right; the ten angles of the conventional double being a large factor. Here are the six angles of the decagon that arc pretty well known and widely used. The numbers will be referred to later.

1. Doubling a suit bid.

2. Doubling a no-trumper.

3. Doubling after having bid a suit yourself.

4. Doubling after having bid no-trumps yourself.

5. Doubling a second time, if partner did not answer the first.

6. Doubling for penalties.

The four which are not so well known or generally used, are these:

7. Doubling opponent's suit, instead of assisting your partner's no-trump.

8. Doubling after having assisted your partner's suit.

9. Doubling after having denied your partner's suit, or having refused to assist it.

10. Redoubling, as a defence to the negative double of the opponents.

The redouble is seldom used as a defence, the hand to justify it being rare; but to each of the other doubles there is a defence, the more common being to increase the partner's bid before the double is answered, so as to make it expensive. The other is to shift the bid.

Taking these various doubling conventions in their order, it might lie well to state their exact meaning, as a guide to the partner's proper reply. There are two points which the beginner is usually misinformed about. One is that the double must be answered. This is a mistake. No one can dictate to the partner what he shall do. The double is a suggestion, just as bidding a minor suit is a hint that a notrumper is much more to be desired. The other error is that the double asks for the longest suit, regardless of its rank.

Doubling Objectives

THE object of the double is to arrive at the best declaration for the combined hands. instead of for the individual hand. This is arrived at by a thorough understanding of the holdings which prompt one player to double, and the suits which the doubler would like to have called in answer to the double.

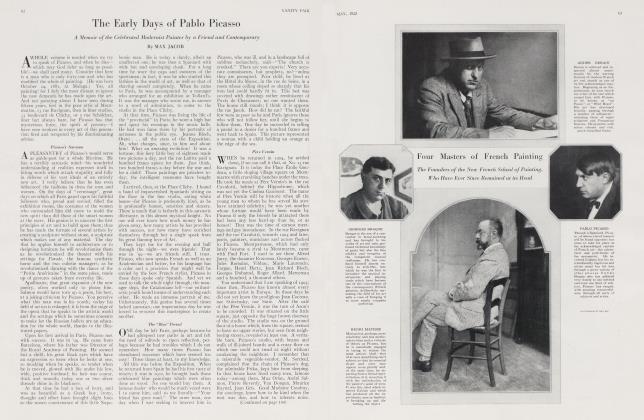

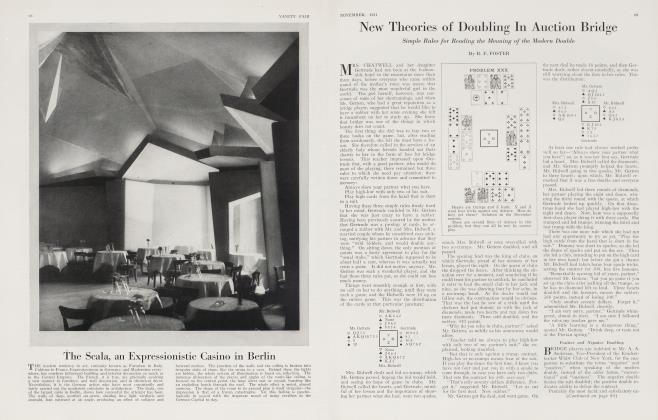

There are no trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want five tricks against any defence. How do they get them? Solution in the June number.

1. The double of a suit bid is limited by three conditions: it must be a double of not more than three tricks; a double of four or more always being for penalties, at any stage of the bidding, regardless of the suit named. The double must be made at the first opportunity; that is, it must be the first time the suit is named. One cannot bid a heart; overcalled by a spade, and then go two hearts, overcalled by two spades, and then double, except for penalties, because the spade call was not doubled at the first opportunity. The double must be made before the partner has done anything but pass, it is unreasonable to double, asking the partner to show a suit, when he has already. declared one. All doubles made after partner has bid mean business.

Here is a curious example of overlooking this condition:

Z dealt and bid a club; A bid a heart, which Y doubled and B passed. Z, mistaking the double of a one-trick bid for a convention, and forgetting that he had already declared clubs, answered the double with a spade bid. He made three odd, with simple honors against him, netting him g points. They would have set the heart contract for 200. Had B tried a spade rescue, when he knew the heart double meant business, he would have gone down 300

When a suit bid is doubled, the partner of the doubler not having made a bid, it indicates that the doubler had a potential notrumper; but that he cannot stand the immediate lead of that suit by the opponents. Whether the suit is bid on his right or left, the double has the same meaning.

There are two answers to the double of a suit. One is to go no-trumps if that suit can be stopped twice, no matter who leads it, which is rarely possible against good bidding. The other is to pick the best suit in hand. As the object of all conventional doubling is to get a game-going contract, preference should always be given to major suits, even if only four cards, and in spite of a five-card minor suit in the hand. There are many cases in which the hand may be such that there would be more in leaving the double alone; either more gains or less loss, especially when the longest suit in the hand is the doubled suit, but without any "tops".

2. The double of a no-trumper takes the place of the old system of going two no-trumps or guessing at a suit, or passing. It is considered useless to double a bid of two notrumps, as game against such a hand is usually impossible, and if partner is very weak, the double may get one into trouble.

The partner should read the doubler for scattered strength, but enough cards to support a take-out in either of the major suits, preferably spades. It has become conventional to call spades on four of any size, even in preference to five hearts.

3. The double of opponent's suit, after having bid a suit yourself, asks your partner to show what he has, if he cannot assist your suit. The nature of the double limits its use to situations in which the partner has refused to assist. Suppose you bid a spade, second hand two hearts, partner passing. The double of two hearts asks partner to call a suit of his own, if he cannot support spades. This double can be made only on hands that have some strong cards outside the suit first named. A common answer is to let the double stand; the hearts being the partner's strong suit.

4. Doubling a suit after having bid notrump is practically the same as doubling the first suit bid made. (No. 1) When a suit is doubled originally, it shows the potential notrumper, .weak in that suit. When a suit is doubled after having bid no-trump, it shows that the suit named has hit the weak spot in the no-trumper.

It becomes the partner's duty to bid the best he has, giving the usual preference to major suits if he has four of either, and to spades instead of hearts, if spades is not the suit doubled.

Continued on page 92

Continued from page 76

5. Doubling the second time, partner having declined to answer the first double when the intervening player took it out, shows that the doubler is willing to have his partner call any four-card suit, no matter how weak. The reason for passing, when the double has been taken out by the intervening player, is usually the absence of any five-card suit, or strength enough in four cards of a major suit. With a five-card suit, the intervening bid is usually disregarded and the double answered, especially with five spades or hearts. It must be remembered that this second double, or even a third, is still conventional; but only if the double was made at the first opportunity, and before partner bid anything.

6. The double that means business and is aimed at penalties, does not usually come until after two or three rounds of bids. It is often objected to by those who would like to double early, to get penalties, especially in no-trumpers; but no call should mean two things. To double for penalties, partner must have previously made a bid, or the double must not have been made at the first opportunity. These things usually postpone it until the bidding is somewhat advanced.

Three Informatory Doubles

THE doubles which are little used are chiefly informatory. They do not ask the partner to show a suit, but rather give him a hint as to where he will find the tricks in dummy if he goes on with his own bid. They are sometimes very useful.

7. Doubling a suit which is bid against partner's no-trumper shows two stoppers in that suit, and at least one sure trick outside. This says to the partner: "if all you are afraid of is that suit, I can take care of it." The great mistake made by untaught players is in going on to two no-trumps. When you assist a suit bid, you know what you are assisting; but when you assist a 110-trumper, you don't know anything about it. Your partner can go two no-trumps, if you double, or he can leave the double in and get good pickings from poor players. If you go two no-trumps, you tie him up, often without knowing it, to your sorrow.

8. The double after having assisted partner's suit bid once, brings it into the business class, as it was not made at the first opportunity; but that docs not compel your partner to leave it in. This double should never be made except with one or more sure tricks in the opponent's suit, and enough outside to have advanced your partner's suit once more. It is better than advancing the bid, as it indicates exactly where the assisting strength lies, which may be very useful information to the original bidder. This double clearly differentiates hands that assist on the ability to ruff, from hands that assist on good cards, especially stoppers in the adverse suit.

9. The double after having denied partner's suit comes under the same conditions as No. 8. Suppose your partner deals and bids a heart. Second hand passes, and you deny the hearts with two clubs. Fourth hand bids two spades. This bid comes up to you. If you have a sure trick or so in spades, and your clubs are good ones, the double may encourage your partner to go no-trumps. Nothing but the double would give him such a good photograph of your hand.

10. The redouble, as a defence, must come early in the bidding. It is very much like the double in No. 3, when your partner has not assisted your suit, as it asks him what lie has. When the bidding is such that a double cannot be used, the redouble may take its place. Here is an instructive example, played at the Knickerbocker Whist Club the other day: Z dealt and bid a spade, which A doubled, Y and B passing. Z realizes that he is in a hole, as Y passed on the assumption that B would take out the double. If it were not for the conventional redouble, Z would be in a bad way. As it is, the redouble opens the bidding again, and gives Y a chance to show his club suit.

When Y was left with his clubs he made three odd. When B went to two spades on his own account, he made it, if Z did not go to three clubs; but when B answered the double by going to notrumps, he was set.

It is rather remarkable that while there has been so much discussion about the use of the double, there has been little or nothing said about its abuse. Little or no attention is paid to the fundamental part of the whole subject, which is the nature and quality of a hand that justifies a double, and the situations that demand special treatment; but that must be left for a future article.

Answer to the April Problem

THIS was the distribution in Problem XLVI; the solution of which hinged upon the adversaries' play.

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want seven tricks. This is how they get them.

Z leads the club ace, and follows with the spade king, which Y trumps. Y leads the club queen, upon which Z discards a diamond. The five of trumps from Y is won by the ace. Z then leads the spade queen, upon which Y sheds the queen of diamonds, regardless of A's play to the trick.

If A discards a diamond, refusing to trump that spade, Z leads a diamond, and Y makes the jack of trumps. Now a club allows Z to over-trump B, and the ten of trumps is good if A over-trumps both.

If A trumps the spade queen, he must lead a diamond, which Y trumps with the jack. Now Z lies tenace in trumps over B for the last two tricks.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now