Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOur Auction Bridge Refuge

A Sanctuary and Retreat for Persistent, Not to Say Incurable, Bridge Addicts

R. F. FOSTER

Our April Bridge Problem

In the April Vanity Fair, the Editor jailed to make it clear that the bridge problem published in that issue, might easily be solved by a number of our readers, and that, in such an event, every successful contestant would receive the prizes offered. Owing to certain difficulties, due to U. S. Postal rulings, we will henceforth discontinue offering prizes for solutions of our monthly bridge problems.

THERE is nothing, in Auction Bridge, so conducive to improvement in the play of the hands as the study of end-game situations, because it is in the end game that most of the tricks are won or lost which really decide the issue. Very good players, who pay strict attention to the fall of the cards, can usually place all the commanding or important cards in each hand, for the last five or six tricks, and the play then becomes a problem indeed.

Vanity Fair will present, from time to time, a number of these little endings, in which there is a trick or two to be picked up by careful management, which tricks would entirely escape the average player.

A Pretty Seven-Card Ending

Hearts are trumps. Z leads. Y and Z want six tricks against any defense. How can they make them?

Mr. Leibenderfer's System

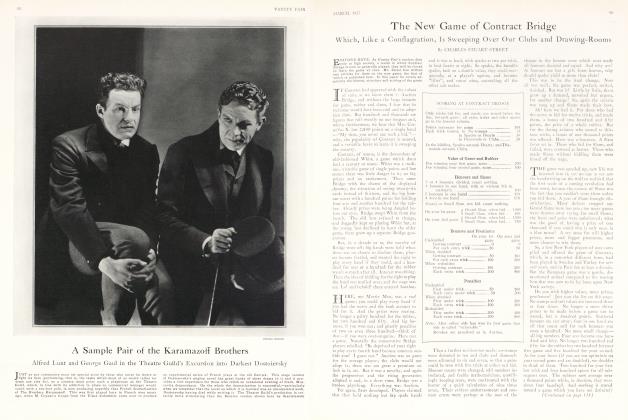

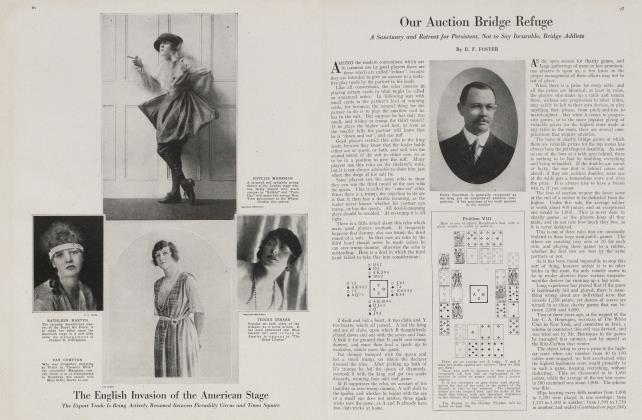

THE system by which Ralph J. Leibenderfer —whose picture appears in this article— has won so many tournaments against all kinds of opponents and with all kinds of partners, cannot fail to be interesting. In an interview he was good enough to give Vanity Fair a brief outline of his methods.

"When I pick up a hand at auction I first look at the score, and then size up the possibilities of my cards very carefully. I memorize every card, so that during the bidding I shall not have to look at my hand again. After deciding what to do, I note carefully the expressions, mannerisms, and modes of bidding of my opponents. The psychological side of auction I consider even more important than in poker, because there is a greater chance for successful bluffing in the bids.

The winning declaration having been settled, if I am opposed to the declarer, I decide upon the best opening lead, and from then on I look at my cards only for the purpose of picking out the one I have decided to play. This allows me to devote my entire attention to the cards played by others. I consider this one of the most important parts of the game. The cards in one's own hand can be seen any time; but those in the tricks turned down are beyond recall if not observed as they fall.

I am very careful about discards. Nothing is so important in saving games and slams* when opposed to the declarer; or in winning them when playing the hand. The end play in every hand hinges upon the discards, which show which hand holds the dregs of a suit, and unless the number and size of each card thrown away is carefully noted and remembered, end plays are impossible. These end plays, forcing discards from opponents when you are the

declarer, or keeping the right cards when opposed to him, are the delight of the expert, and should be the aim of all who wish to excel at auction. Discarding is the key to almost every bridge problem, as such problems are, in their essence, nothing but end games."

Concerning Seats and Cards

THE professional gambler has a theory that the reason one can never be a consistent winner at faro is because one has to do the guessing. The banker never guesses. He sits still and takes his luck as it comes, secure in the belief that time at last will defeat the guesser.

There is a man in New York who is always anxious to bet against the superstitious player that insists on taking the winning seats at auction, instead of remaining where he is, because the player is always doing the guessing. There are persons who consider it more important to deal with the cards that brought them together as partners in the cut, than it is to understand each other's bids. On the other hand, there are some who do not insist upon anything except that they shall be allowed to keep the pencil with which they scored the last rubber, in spite of efforts on the part of the other players to appropriate it.

The remarkable thing about the choice of seats is that it is always the winning seats that are selected, no matter how long they have been winning. The theory seems to be that the luck will continue to flow in only one direction, while it is a well-known fact that, year in and year out, the seats will divide equally the number of games won.

It is also a curious paradox that while these players believe that luck has "runs," they also believe that, if they have bad luck to-day, it must certainly change to-morrow. They imagine that if they lose a large number of rubbers this week, they are due to win a large number next week. Why cannot they see that it is just as likely that the luck of the seats will change for the next rubber as it is that their personal luck will change from day to day?

It may interest some of these superstitious players to know that a careful record of both seats and cards has been kept on more than one occasion. In a thousand rubbers played consecutively at a table reserved for the purpose at Almack's, in London, it was found that the number of times the winning of the rubber shifted was almost exactly the same as the number of times the same seats won again. The largest number of consecutive wins was ten; but six rubbers in succession were won by the same seats seventeen times. This is very close to mathematical expectation.

Some persons consider a knowledge of cardtable hoodoos quite as essential to success as a knowledge of the leads. For the benefit of those who are not familiar with the most effective remedies for bad luck, the following quasi-flippant collection may be useful.

In choosing seats one must consider how the previous games have run. If the seats have been winning, turn about, choose those whose turn it is to win next. If certain seats have had a run of winning, take them if you believe in runs; choose the others if you believe in the maturity of the chances. If you are not superstitious and your partner is, let him do the choosing.

In choosing cards, the same principles apply, but you must be careful to observe whether the cards won with certain seats, or in spite of them. If there is a conflict between the seats and the cards, choose those in which you have the more faith, always trying to get both cards and seats to fit your belief.

When you have a run of bad luck, consider a moment, whether it is owing to bad play on your part, bad cards, or a bad partner. If it be the first, it might do to change your game; try bidding no trumps without an ace, or doubling without a sure trick. If it is bad cards, walk around your chair three times, but be sure to walk in the right direction, or you will only make matters worse.

Continued on page 88

Continued from page 59

Nine times out of ten you will find that the fault is with your partner. Next time you cut for partners, wait until your Jonah has drawn his card and then take the second one from it, in either direction.

If your hands never seem to fit, try sitting with the grain of the table, no matter which seats or cards won the last rubber. If you find that, no matter what you lead, you would have done better to lead something else, lead out of turn once, and let the declarer call a suit. If you cannot get a mascot to overlook your hand while you are bidding, at least see that no one is resting his feet -on the rung of your chair. If you always lose when wearing a particular scarf pin, present it to the player whom you have not yet cut for a partner.

Persons not versed in psychological phenomena will tell you that none of these things has the slightest effect on the result. If that is true, you can lose nothing by trying them; if it is false you must inevitably gain by them.

A Freak Hand

THERE is always a peculiar fascination in a freak hand. It illustrates the never-ending possibilities of the game. When the results are due to atrociously bad bidding, or play, they are hardly worthy of notice; but when both bidding and play are fairly logical, they are frequently not only interesting, but instructive.

Frederic Jessel, of London, author of the "Encyclopedia of Playing Cards and Gaming," has written me that, in a recent rubber at the Portland Club, in London, famous for its fine players, the dealer bid up to three diamonds, doubled and redoubled. The player on his left, who had done the doubling, then bid four diamonds; was overcalled with four hearts on his left, and went to five diamonds, doubled, which he redoubled, only to make a little slam.

This seems almost impossible, but here is the hand, Z being the dealer:

Z started with a diamond, A one heart, which Y doubled. B then bid three clubs, to indicate that his hand was good for nothing unless clubs were trumps. Z went to three diamonds, and A doubled. He cannot go no trumps with no club to lead and his hearts doubled on his left.

When Y and B passed, Z redoubled. He reads his partner's double of the hearts as encouragement to go ahead, and he has every suit stopped. A then began to do a little thinking. He finally decided upon preventing any bidding by Y, and so went to four diamonds. Here Y went—very foolishly—to four hearts, B and Z passing, and A, instead of doubling the hearts, going to five diamonds. Y and B passed, Z doubled, and A redoubled.

Here is the play. Y led a heart, B discarded a club, and the heart jack won. Dummy ruffed the small heart

and led the ten of trumps, which Z covered with the jack. This is a mistake, but a very natural one, and cost a trick, but passing would not have set the contract. A ruffed dummy again with a heart and led the jack of spades. Z covered and A won.

A then led ace and another trump, forcing out the king. Z led the king of clubs, which B won, returning the smaller spade, which A won; A then pulled both of Z's trumps, made his ace of hearts and led the small spade to dummy's ten; little slam.

Overcalling No-Trumpers

I HAVE always advocated letting sleeping dogs lie. If the player on my right bids no-trumps, I pass, no matter what I hold. I may miss a game hand occasionally, but, in the long run, I am a long way ahead of the game by leaving the alleged no-trumper to work out its own salvation. If I have what most players would consider a bid, and can make game on it, the no-trumper would have been badly hurt if left alone. If I cannot make game, I am playing for 6 to 8 a trick, when I might have been playing for SO. The usual result of making a bid is to drive the no-trumper into a safer declaration, at which he can go game, or at least save himself from the penalties that he would have incurred at no-trumps.

Here is a hand, recently played at the Knickerbocker Whist Club in New York, by four persons who are supposed to be experts. It is an excellent example of the importance of letting no-trump bids alone.

Z dealt and bid no-trump. Whether or not this is a legitimate no-trumper is not the question. That is the way many players bid them now. Z has a big minor suit and three suits stopped. The chief interest lies in A's hand. He can do one of three things: double, bid two no-trumps, or pass.

If he passes, Y and B say nothing, and A holds the declarer down to the odd trick, scoring 100 aces against him. It is manifestly impossible for Z to win the game against A's cards, as he can lay down five tricks before he loses the lead. If A opens the diamonds, he will set the no-trumper for one trick.

If A doubles, Y at once interposes a club bid, while it is cheap, and B bids two spades. Y went to three clubs and B to three spades, in the actual game, which Z doubled and A redoubled, being set for 200.

If Y had been left to play the hand at clubs, he would have been set, as he cannot make three clubs. A can lay down four sure tricks against the club contract and still hold a potential tenace in trumps over Y, who will find himself with a trump too many at the end. If Z takes out the clubs with the diamonds, bidding three, he will be doubled and set for 400.

This hand is an extreme example, but the fact remains that more money can be made, by refusing to go two no trumps after the dealer on your right has gone one (or even to bid two of any major suit), than can be made by allowing the dealer to play the hand as a no trumper.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now