Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Midwinter Plays

An Outburst of New Plays Starts the Glad New Year

DOROTHY PARKER

THERE really isn't much to say for the life of a critic. In the first place, it is entirely too spotty. There are long, quiet stretches when he hasn't a thing to do with his evenings, and then there are sudden outbursts of such violent activity that he nearly succumbs to apoplexy. If only the managers could be induced to spread things out a trifle thinner, much, unnecessary suffering would be averted.

But no—managers aren't that way. The congested condition of the new plays is worse than ever. Before Christmas, for instance, there were two long weeks with not a single opening anywhere about them; the managers might just as well have carried out the idea and pasted decorative placards saying, "Not to be opened till Christmas," on the doors of their theatres.

But just as soon as the joyous Yuletide hit town, the managers suddenly unleashed a whole drove of new plays and set them on the public. It cut in horribly on the critics' holidays. On Christmas Eve, when everyone else was safe at home trying to make the children's new mechanical toys work, there were the critics, out in the bitter night, striving to see seven openings at once. Oh, it's a rough life, a critic's is.

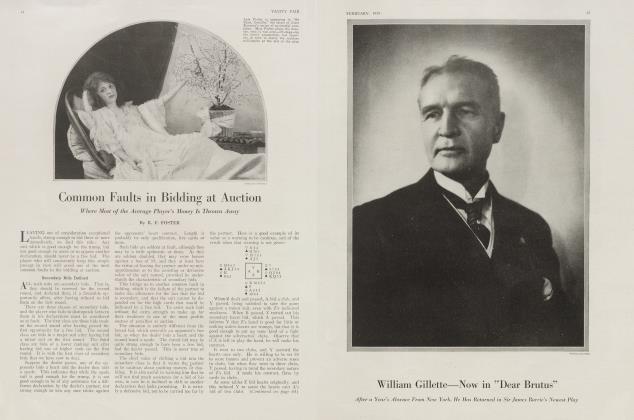

But then, it does have its compensations. For example, there is "Dear Brutus," the new Barrie play at the Empire. Seeing that really does make up for practically everything. So far as I am concerned, it is one of the big things in life. Of course, the minute you start to say anything about a Barrie play, you immediately bore everyone around you to the verge of tears. There is simply no use in trying to tell about it—the only thing to do is to go see it as soon as possible, which will probably be some time in Easter week, from the way the house is selling out. It is practically impossible to talk about the play without bringing in "whimsical charm," and that spoils everything. People are so everlastingly fed up with the poor old term that they say, "Oh, yes, it must be another of those things—let's go to the movies." But there you are; the play is simply packed with whimsical charm, and what can you do about it? And, after all, it does seem pretty good to call something charming for a change; it is certainly delightfully restful to see a play wherein nobody swears at anybody, or shoots anybody, or seduces anybody, or goes to war about anything. The outstanding feature of the Great Dramas of this season is their thorough and exhaustive lack of charm. You can count the exceptions on the fingers of one hand,—and have a thumb and two or three fingers left over.

Well, anyway, "Dear Brutus" is to me the event of the season. Besides the well-known charm, it holds you interested and entertained every second, and there are few other plays of the season that keep you right along with them all the way through. I don't know whether you feel that way about it, but I think it is a far better play than "A Kiss for Cinderella" was. I will admit that I got a bit sunk in the whimsicalities of "A Kiss for Cinderella," but "Dear Brutus" never cloys for a moment.

It isn't just the play itself—there is the excellence of its acting, too. Those whimsical things can be so completely ruined by an over-sweet performance. I shudder to think how sticky the whole thing would have been with a less able performance than that of William Gillette. The ladies' cup goes to Helen Hayes, who does an exquisite bit of acting. Hers is one of those roles that could be over-done without a struggle, yet she never once skips over into the kittenish, never once grows too exuberantly sweet,—and when you think how easily she could have ruined the whole thing, her work seems little short of marvelous. I could sit down right now and fill reams of paper with a single-spaced list of the names of actresses who could have completely spoiled the part.. The cast of "Dear Brutus" also includes Louis Calvert, Sam Sothern, Hilda Spong, and Violet Kemble Cooper—you can see for yourself it's a big evening.

Altogether, "Dear Brutus" meant practically everything to me. It made me weep —and I can't possibly enjoy a play more than that.

"EAST IS WEST" brought the tears to my eyes, too, but they were tears caused by extensive yawning. It is one of those plays where you can guess what is going to happen all the way along, if you can only work up the interest. It is a Chinese play, and you know how those things are —the love of the Chinese heroine for the American hero in the white trousers; the Chinese villain, wealthy, influential and head of a tong; the pidgin English; the selection from "Butterfly," during the second intermission, and all the rest of it. "East Is West" is strictly according to formula, except that it seems a good deal worse than is absolutely necessary. The heroine turns out to be not Chinese at all, in the last act, but an American girl, stolen in her infancy,—which makes the whole thing seem such a useless fuss, if she was going to go and be an American all the time.

The authors, Samuel Shipman and John Hymer, haven't missed a trick. All the old ones are there—the heroine's refusing to worship Chinese gods, and her frequent pulling of a crucifix from her Oriental camisole and praying aloud, holding it on high; the conversation about the moonlight, the flowers and the little clouds; the hero's house, with affluence shown by a property butler, and an over-abundance of cocktails; the mother with the prematurely talcumed hair; and the getting of a laugh by means of the words "hell," "damn," "chicken," and "shimmie," uttered by the guileless heroine. And the worst of it was that the audience at the Astor Theatre fell for all those things, the night I was there. They were just as excited as if it were all new stuff.

I have heard it said that it took Messrs. Shipman and Hymer just three and a half days to write their drama. I should like to know what they were doing during the three days.

Fay Bainter is so persistently kittenish in the leading role that it was all I could do to keep from rising in my place and appealing to her personally,— "Please, Miss Bainter, won't you stop being cute for just two minutes? You don't know how I should appreciate it." I can't quite fathom why George Nash, who plays the part of a Chinaman, should use a pronounced Italian accent. If Mr. Nash's peformance was meant to be a huge joke on the audience, it was perfectly corking; if he was in earnest, it was distinctly something else again. Forrest Winant plays the white-flanneled hero in the conventional manner—invariably resting one foot on whatever elevation happens to be convenient, and bending over to clasp his hands on his upraised knee. Judging from the pose, I expected him to burst into a waltz song any minute. Hassard Short has a minor part, showing what can be done with it, and the honors of the evening go to Lester Lonergan. The scenery and the costumes look as if they had been designed by Sears, Roebuck.

Continued on page 74

Continued, from page 39

FROM what I could hear of it, I gathered that "The Gentile Wife" is a very interesting play. The actors in Rita Wellman's drama deliver the major part of their speeches with their backs toward the audience, which renders it a bit difficult to gather just what is going on. In fact, I think I should have heard a good deal more of the proceedings if I had left the Vanderbilt Theatre and gone and stood out in the middle of Forty-seventh Street, in which direction they were all facing. On the few occasions when the people on the stage so far forget themselves as to do anything so theatrical as facing the audience, they spoke in such Confidential tones that I felt unpleasantly like an eavesdropper and tried not to listen. It would greatly heighten the enjoyment of the play if the ushers would sell librettos, so that the audience could follow the story.

However, the few things I could manage to overhear seemed to be very good, and, anyhow, Emily Stevens' acting always interests me greatly, and she is unusually good in this. Vera Gordon contributes a remarkably fine and a delightfully audible characterization. Unfortunately, one of the few speeches, besides hers, that I could hear was that of Frank Conroy, who read a bit of a French poem aloud. Anyone with an accent like Mr. Conroy's should read aloud only in English.

"THE LITTLE JOURNEY," Rachel Crothers' new comedy, is pleasantly mild and restful. If you want a nice long rest, with nothing particular to think about, do drop in some evening. For two of its acts, it is gently amusing, but the last act is a bit sticky. The play is one of those affairs the scene of which is laid on a train,—but don't give up in despair, for it's so well done you will hardly mind at all. At the end of the second act, there is a railroad wreck so convincing that the entire audience feels in need of first aid. This wreck is to blame for the last act—for, startled and sobered by their narrow escape, all the characters become regenerated and change into paragons of virtue. The heroine is supposed to have been hit on the head by a piece of wreckage, which causes her to become remarkably tiresome. She talked about her soul and a brighter, sweeter life, until I found myself wishing that she could only have been hit harder, and made unconscious.

The heroine's part is charmingly played by Estelle Winwood, who proves herself to be one of the few actresses that can fuss over a property baby and not make you look around for the nearest exit. Cyril Keightly is the Westerner who saves her in the wreck, and then marries her, as they always do. Jobyna Howland is most amusing, until her role goes bad on her and she has to become virtuous, and Victor LaSalle and Theodore Westman, Jr., come in for honorable mention. Perhaps the best thing about the play is that it is an excuse for re-opening the charming Little Theatre.

"Oh, My Dear," at the Princess Theatre, simply goes to show that no one can do musical comedies the way P. G. Wodehouse and Guy Bolton do. This time, Louis Hirsch is the third party in the case, contributing the music in the absence of Jerome Kern. His music is so reminiscent that the score rather resembles a medley of last season's popular songs, but it really doesn't make any difference,—Mr. Wodehouse's lyrics would make anything go. The cast helps to make the time pass pleasantly—Juliette Day and Roy Atwell in particular. If only steps 'coiild have been taken to have prevented Ivy Sawyer from sounding the "t" in "often" and to have restrained Joseph Santley from saying "avviator," my happiness would have been complete.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now