Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAre You Built to Play Golf?

Technical Form and The Human Form Are Not Necessarily Related

GRANTLAND RICE

You may be lean or fat or tall Or rounder than a well fed Nero; As long as you can hit the ball The rest of it is less than zero.

For in the old game's growing guild Where countless thousands swing and suffer, A man may have a perfect build,

And still may be a perfect duffer.

A LARGE, thick, chunky citizen steps up to the tee, swings at the ball, lifts his head and then as the stroke goes badly astray you can hear him moodily remark—

"What's the use, anyhow? I'm not built for this game and I'll never play it right."

Among the countless alibis that go hand in hand with bad golf this matter of the human frame is one of the most extended of them all.

The fat man says he is too fat to play. The thin man says he is entirely too thin and lanky. The tall man says he is too tall to control a proper swing and the small man says he is too greatly handicapped by lack of bulk. We recall one big powerful athlete, an old football star, perfectly muscled and weighing 230 pounds who after many trials said he would never be able to play well as he could never control his muscular development and his physical power sufficiently to handle a game requiring so many delicate strokes.

An Example

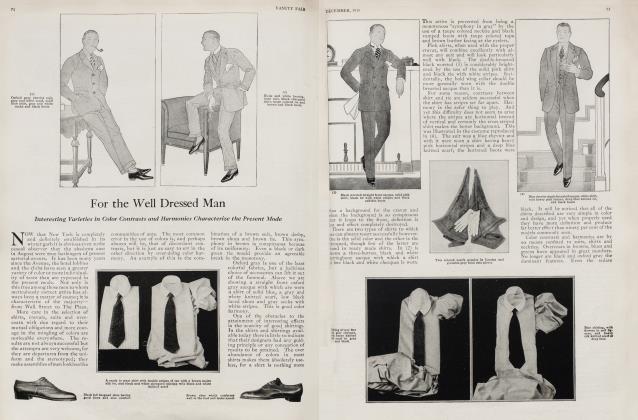

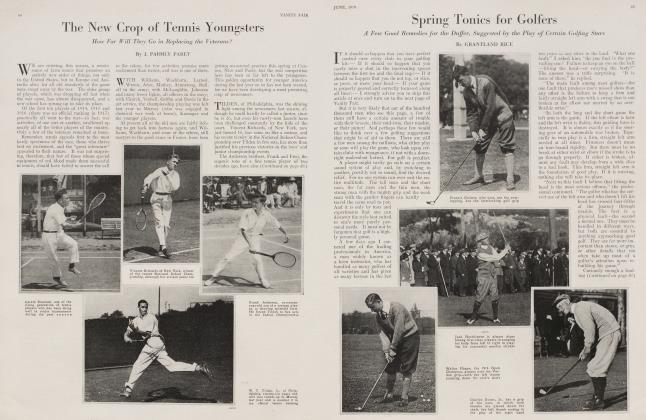

IS par golf a matter of physical build? Suppose we take up the matter with a few human illustrations. The recent professional championship was under way at the Engineers' Golf Club near Roslyn, L. I. Over this fine course one of the greatest fields of the year came to battle for the big prize. Who reached the final round? Two tall men? Two fat men? Two thin men? Or two what not?

One of them was Jim Barnes. Barnes isn't quite so tall as the Woolworth bulling or the high cost of living,. but he can give both a battle for altitude. His gaunt and willowy frame extends into mid-air after the manner of the steeple on a French church. From far away you can see that shocky head of his drifting on through the morning mists. He is 6 feet 4 if he is an inch and a half. He was one of the field to plough his way safely through. The other finalist was Freddie McLeod. Ever see Freddie? Probably not, unless you looked twice or had a pair of field glasses along. Freddie is a wee Scot about the size of a short putter. He won the open championship at Myopia many years ago when he tipped the beam with a displacement of 118 pounds. He stands around five feet six when he rises on his toes. Yet, like Barnes, he fought his way through a hard half, beating fat men and lean men, tall men and short men, plump men and skinny men, on his way to the goal. Barnes, 6 feet 4, defeated McLeod, 5 feet 6. But it wasn't because Barnes was taller by the length of a put. For McLeod was getting almost the same distance with both wood and iron but it so happened that in this match his putter went astray and left him stranded on the moor.

Or Another

THE final round of the Amateur Championship is under way over the rugged, rolling Oakmont course—one of the great golf courses of the world. In this championship there had been entries of every conceivable build. There was Francis Ouimet, thin and willowy. There was Chick Evans, compact and leanly set up. There was Bob Gardner, with the mold of a track star, the make-up of a star all-around athlete. There was Max Marston and there was Oswald Kirkby, both possessing what is technically known as the "ideal build" for the game.

But who reached the final round? One was an amazingly rotund young man who at the height of 5 feet 7 or 8 inches weighed 218 pounds. There was certainly nothing svelt or wiry about him. When he entered one cf the big, yawning traps he almost filled it. You wondered at times where he found room to swing. But he always found it, and when necessary to get the ball out he frequently took part of the trap with him.

The other was a well built youngster of 17. His name was Bobby Jones. Three years ago at Merion he was 5 feet-S and weighed 155 poundsv Three years later at Oakmont he was 5 feet 7 and weighed 136. He had gained 2 inches and had lost 20 pounds in 3 years. Yet this pair, absolutely different in build, had not only fought their way through the big field but had also been two of the longest hitters of the tournament. Both were slashers from the ancient Indian village known as Hit-'em-a-mile. Neither had the lankness or length of frame that is supposed to go with great distance, but they got it, just the same, and in copious quantities. They proved again beyond any debate that championship golf is not a matter of width so far as the human frame is concerned. They proved it effectively by playing the best golf in the tournament, and in the final test it was the chunky entry who finished first.

(Continued on page 106)

(Continued from page 70)

The Complete Proof

THERE we have together two of the big champions of the year in the amateur and the professional field. Consider them side by side. One is tall and thin—6 feet 4 and weighing less than 150; the other is thickset and rotund, 5 feet 8 and weighing 218. It would be almost impossible to find two men more dissimilar in build. They are exact opposites—yet each has proved his ability to play the highest class of golf—to play all strokes—to get great distance from the tee—to use an iron—to swing with both form and power.

Bob McDonald, probably the longest hitter of the year, is tall and rangy, a powerful Scot. But McLeod, weighing around 120, can get far enough to give any man a battle. McLeod is the only professional golfer we know of who had consistently stuck in the money for the last 15 years. No other golfer can equal him in this respect. While tall men such as Barnes— powerful men such as McDonald, and thick-set men such as Hagen can get great distance, so can smaller men such as Bobby Jones and Norman Maxwell who by getting additional leverage with their hands carried well above their heads can send the ball spinning as far down the course as the mightiest sluggers of the game.

Jerry Travers weighed only 130 pounds when at his best. His hands, too, were small and thin, with fingers much shorter than the average. He had a pair of hands that never appeared to be built for distance. But who can forget, the long range he found with his driving iron in the days when he discarded the wood? He could tear into an iron shot for as great a distance as most stars could get with the wood. Yet, in a physical way, he was not put up for any such ground-covering range.

No, golf is not a matter of the physical build. It is a game for all the varied assortments that go to make up a fairly varied universe. No man—and may we not say— no woman—can use his or her human make-up as any alibi for a groggy round. The fact that you are thin or fat or tall or short doesn't make you lift your head or break your swing or hit too soon or fail to time your strokes. And these, in the main, are the canny details that put 7's, 8's and 9's upon your card and turn your suffering soul inside out.

Lives of golfers oft remind us We can have a perfect frame,

And, departingleave behind us Rounds that mean a life of shame

Let us then be up and doing With a heart for any score,

Still achieving, still pursuing, Though we wear a forty-four.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now