Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOur Need of a New Remount Policy

The Experience of the Army in France Has Proved Conclusively the Necessity for Better Horses

O'NEIL SEVIER

THE American infantry which helped France, the British, Belgium and Italy to humble German insolence was all that infantry should have been as military specialists everywhere concede. American infantry was not as superlatively superior to the infantry of western European powers and of the British dominions, perhaps, as American chauvinists would like to think and to have the world generally think, but there can be no question that in the sovereign qualities of cheerful courage, resourcefulness and perseverance it was not excelled by the veteran infantry of Canada,

Australia, Great Britain and France. In murderous efficiency,

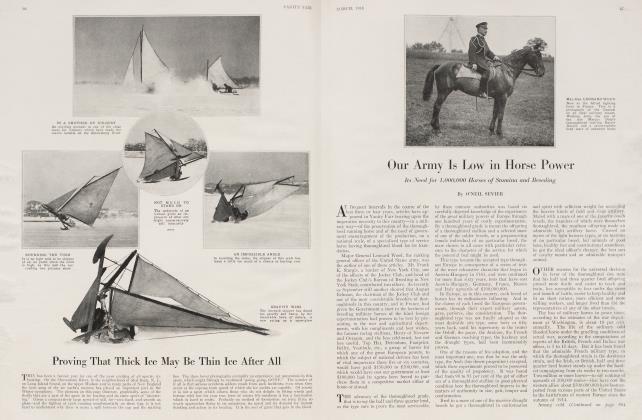

American heavy artillery, the artillery that made use of gasoline motor and portable railroad transportation and the heavy draught types of horses for moving guns and ammunition, was as good as the best Yankee infantry.

But here we must halt our praise of the combat branches of the A. E. F., at least as regards their demonstrated military efficiency. American field artillery generally was only passably effective. The American transport service, because of the marked inferiority in general efficiency of its horses, fell considerably below the best European standards, allied or enemy. There was no American cavalry. Beyond question it will be found when the records are examined and expert testimony is digested that there were Stonewall Jacksons, Longstreets, Meades and Thomases among the general officers who directed the movements of the divisions which stopped, at Chateau Thierry, the German rush on Paris and hewed a bloody way through the concentrated Hun masses in the Argonne to the vital railroad junction of Sedan. But there will be no Sheridan, no Forrest, no Wilson, no Stuart, no Kilpatrick, no Joe Wheeler for coming narrators and novelists to celebrate in history and fiction.

IF Germany had not shown the yellow that was in her in November, when her armies on various fronts were still at least equal in numbers and not at a hopeless disadvantage, as regards equipment, to the forces of outraged civilization, and had put up a fight to prevent desecration of the soil of the vaunted fatherland; if the war had at last been transformed into a war of movement, involving an invasion of German territory beyond the Rhine, the work of that great forward allied movement that devolves on mounted troops would, of necessity, have fallen to the not too numerous cavalry of Great Britain, France and Italy. If American field artillery had been called on to play its proper part in a great offensive toward Berlin it would have been necessary to have rehorsed it out of the equine reserves of Great Britain and France.

When the war came to its unexpected finish America had under arms at home and abroad a grand total of 3,700,000 soldiers* of which 389,000 were field artillery, but only 29,000 were cavalry. The field artillery was horsed after a fashion. So was the engineer, contingent. For such masses of infantry and artillery the proportion of cavalry should have been 250,000 sabres, according to the most advanced military opinion. Yet only a fraction of the absurdly small mounted contingent of the great American military organization of November 1st, 1918,—the 2d, 3rd, 6th, and 15th regiments—was in France. Most of the 29,000 troopers were patrolling the Mexican border and wishing they were dead.

Moreover, only a moiety of the so-called American cavalry actually in France was mounted. At no time was it possible to completely horse the 2d, 3d, 6th, and 15th regiments. There were no really accepted mounts available. France and Great Britain might spare artillery horses of serviceable types because, up to the last few weeks of the titanic struggle between the nations, that struggle had been largely a war of position and an affair of infantry and artillery. They could spare no horses for the troopers of an army that should have entered the conflict with the best-mounted and best-equipped cavalry to be found in the world.

(Continued on page 84)

(Continued from page 62)

"A branch of the service," to quote George Rothwell Brown, "that in all previous American wars had not. only been the most typically American and picturesque, but one of the most serviceable, was practically unrepresented on the battle-fields of France. Most of the American cavalrymen in France were compelled to do their bits as unmounted troops in the S. O. S., back of the lines or serve as infantry or field artillery."

THE lot of these unhorsed troopers in France was harder than that of the troopers left behind on the Mexican frontier. But had they been mounted as well as it would have been possible for the American remount service to mount them their status would have been hardly less humiliating. Because of the indifferent quality of the only horses that might have been assigned them they would have been condemned to patrol work behind the advancing victorious lines, whipping up stragglers —if there had been any stragglers—and forwarding ammunition and supplies.

Caspar Whitney, writing of the A. E. F. field artillery and transport horses that took part in the crucial Argonne drive says: "Our poor horses during the Argonne drive were a sight to make the gods weep. Mostly they were culls, left over after our short-sighted and parsimonious government had refused to pay more than $150 a head for military horses." Some of these animals were horses that had actually been sold by American farmers to Great Britain and France earlier in the war and resold in France to officers of the remount service of the A. E. F., at from $400 to $700.

The experience last June of the artillery brigade of the 2d, regular division of the A. E. F., one of the best equipped, as to its horseflesh, of the American units that served in France, was typical of the experiences of American field artillery generally. Ordered, with a couple of French divisions, from a quiet sector near Verdun to Chateau Thierry to meet the Ludendorf thrust that was to win Paris and peace, the 2d division undertook a march of no more than 100 miles. Yet 80 per cent of the horses of the artillery brigade of the 2d division were out of the running before the infantry regiments reached their objective, although the division had not come within the range of hostile guns. The accompanying French divisions lost less than 5 per cent of the horse strength of their cavalry and artillery contingents.

THE artillery brigade of this 2d division, the division with which the famous marine regiments served, was a day late in reaching Chateau Thierry. Its guns did not open on the Germans until the second day of the battle, which proved to be the turning point of the war. That this brigade finally reached Chateau Thierry was due to the preparedness of the French remount service to rehorse it with half and three-quarter breds from French base stations. Not 10 per cent of the nondescript horses of the artillery brigade of the 2d division that had proven unequal to a march of 100 miles were fit to be sent back to base stations for recuperation and restoration to active service. Such as were not de- stroyed and skinned for their hides were abandoned to peasant farming folk, perhaps for the table.

(Continued on page 86)

(Continued, from page 84)

Twenty thousand properly mounted cavalry would have converted the German defeat at Chateau Thiersy into a disintegrating rout, entailing the loss of tens of thousands of prisoners and innumerable guns and material, according to American cavalry officers recently returned from France. Two divisions of mounted troops at St. Mihiel, where, by flattening out an irritating salient which had tortured the French battle line for three and a half years in a few days' fighting, the infantry and artillery of the A. E. F., first demonstrated their merit to an expectant but skeptical Europe, would have converted a mere defeat of German arms into a disaster comparable in ultimate results to that of Auerstadt and Jena. The same unimpeachable authorities declare that two divisions of cavalry operating with the American and French armies in the Argonne forest would have made another -Sedan, with the consequences of the French debacle of 1870 reversed, and compelled the surrender of 200,000 men two weeks before the signing of the armistice.

THE defeated and demoralized German infantry and artillery were jumbled together in almost hopeless confusion for days before the appeal for the armistice was sent to President Wilson in a terrain free of wire entanglements in which cavalry might have manoeuvred with brilliant results. Skillful leadership succeeded in extricating them because the attacking infantry and artillery, owing to the difficulty the S. O. S. encountered in bringing up supplies and ammunition, could only creep.

The weakness of the British cavalry divisions in relation to the infantry masses of the armies which operated in Flanders in October under Sir Douglas Haig prevented the commander of the northern wing of the allied attack from properly exploiting the brilliant successes won by his foot troops and splendidly served field guns. Two divisions of first-rate cavalry pouring through a gap that might easily have been made in the so-called Hindenburg line by an intensive artillery and infantry operation in the Verdun sector could have destroyed German communications in the Rhine valley and blown up innumerable bridges a fortnight before the first American division reached the neighborhood of Sedan. Germany could not have met such a raid with good cavalry.

The embarrassment of the A. E. F., due to the indifferent horse equipment of its field artillery and transport services and its utter lack of cavalry; an embarrassment that would have overwhelmingly handicapped an American army operating on home soil, or in a foreign country, without better outfitted allies, against an enemy of the first class, was the inevitable and discouraging consequence of the criminally stupid refusal of congress to heed the pre-war warnings of enlightened army officers and studious experts of the agricultural department that the automobile, the rural trolley and general railroad development had practically put a stop to the breeding by farmers of horses of serviceable military types and that government encouragement to highly organized production of special military kinds was more than imperative.

CONSPICUOUS among the soldiers, who, for fifteen years before the outbreak of the great war, had been demanding liberal appropriations and systematic legislation for the establishment and maintenance of a national horse breeding organization to be directed jointly by remount specialists and agricultural department experts, were General Leonard Wood, General Hugh L. Scott, General Henry T. Allen, General Robert M. Danford, General Frank R. McCoy, General E. St. John Greble and General Gordon Johnston. The recommendations of these accomplished soldiers had been warmly seconded by George M. Rommel and A. D. Melvin of the Department of Agriculture.

General Danford, now chief of the artillery brigade of the division training at Camp Jackson, South Carolina, is properly regarded in military circles as the army's super specialist of the remount problem. Sent abroad some ten years back to study the remount systems of Europe, General Danford, then a lieutenant of field artillery, made exhaustive observations in France, Germany, Italy, Russia and Austria-Hungary, and then came home to write a report that is recognized as a classic in war department literature on the subject. General Danford showed that Europe, after a century of experimentation, a work that had cost the great powers collectively about $100,000,000, had come separately to the unanimous opinion that thoroughbred blood was indispensable in the military horse. He made the daring recommendation that the government buy immediately, and in its entirety, the famous thoroughbred stud of'the late James R. Keene, which was then in the market. It was his idea that this stud should form the nucleus of a great national military breeding establishment.

THAT this state of disgraceful unpreparedness to equip cavalry, artillery and transport for effective warfare, defensive or offensive, cannot be permitted to continue if the United States are to take a big nation's part in the future regulation of the affairs of the world, whether under the Wilsonian league of nations theory, a new balance of power arrangement, or in a catch-ascatch-can scramble, is obvious. That provision for the stimulation of systematic and voluminous production of horses of proper types must be made ahead of any other military preparation specialists of the remount service are urging with the utmost vehemence.

Provost marshals cannot call American horses to concentration camps for intensive training in the expectation that in six or seven months they will graduate finished specialists as they did the young manhood of the country. As I have pointed out already, America's once famous breeds of tough and enduring horses have about disappeared. A new breed must be called into being, and it will take five years to bring to the firing line a horse bred especially for military service.

The experts of the American remount service have accepted without reservation European endorsement of the thoroughbred grade as the type sure to give the most satisfactory military results, so the country will not be called on to spend vast sums and waste precious years experimenting with breeds. The only thing congress has to do is to create the machinery for the purchase and management of some eight or ten thousand suitable thoroughbred stallions, finance the enterprise on the scale demanded by its essentialness to national safety, and to make proper provision for a campaign of educational publicity. The publicity angle of this proposition is not its least important one, either. Ignorance of horses and the values of breeds among Americans generally is almost unbelievable. It has been no great while, in fact, since a colonel of the army in all innocence and ignorance asked an official of the department of agriculture whether or not a thoroughbred could trot. The least costly part of this enterprise will be the acquisition of stallions.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now