Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSir Barton, the Chestnut Hope

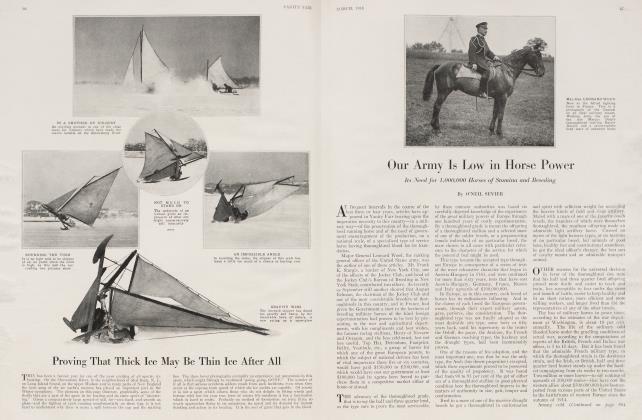

A Horse Which Has Excited Even the Old-Timers

O'NEIL SEVIER

THE most difficult men in the world from whom to wring an admission that any horse of the present day may be as good as was some renowned flyer of the past are the hardshelled trainers of twenty-five to thirty years' experience at racing. To them Hindoo, which flourished forty years back, was the incarnation of speed, the embodiment of equine courage, the last word, in short, in thoroughbred merit. The finest thing they can say of a horse even at this remote day, is that he has the speed of a Hindoo.

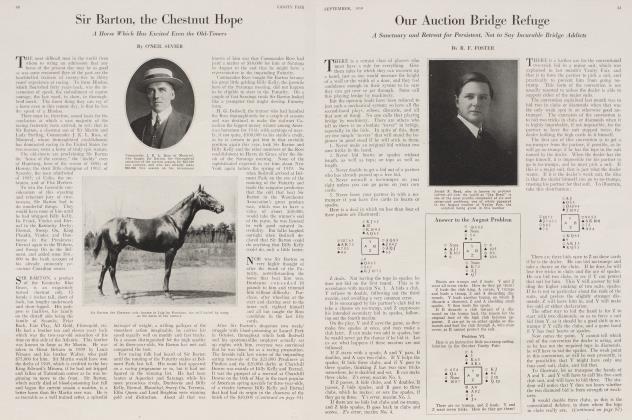

There must be, therefore, sound basis for the conclusion at which a vast majority of the racing fraternity have arrived, to wit: that in Sir Barton, a chestnut son of Sir Martin and Lady Sterling, Commander J. K. L. Ross, of Montreal, whose thoroughbred establishment has dominated racing in the United States for two seasons, owns a horse of truly epic stature.

The old-timers are proclaiming Sir Barton the ''horse of the century," the "daddy" even of Hamburg, hero of the season of 1898; of Hermis, the stout little champion of 1902; of Sysonby, the roan whirlwind of 1905; of Colin, the unbeaten, and of Fitz Herbert.

To win the favorable consideration of this exacting and reluctant jury of crustaceans, Sir Barton had to do wonderful things. They would have none of him until he had whipped Billy Kelly,

Be Frank, Vindex and Eternal in the Kentucky Derby;

Eternal, Sweep On, King Plaudit, Vindex and Dunboyne in the Preakness;

Eternal again in the Withers, and Sweep On in the Belmont, and added some $66,000 to the bank account of his already eminently pecunious Canadian owner.

SIR BARTON, a product of the Kentucky Blue Grass, is an exquisitely turned chestnut colt, 15 hands 3 inches tall, short of back, but lengthy underneath and short-legged. His pedigree is faultless, his family on the distaff side being the family of Sysonby, Friar Rock, Fair Play, All Gold, Flittergold, etc. He had a brother ten and eleven years back which was the two-year-old sensation of his time on this side of the Atlantic. This brother was known to fame as Sir Martin. He was taken to Great Britain in 1909 by Louis Winans and his brother Walter, who paid $75,000 for him. Sir Martin would have won the derby of 1909, which is credited to the late King Edward's Minoru, if he had not tripped and fallen at Tattenham comer as he was beginning to move to the front. Sir Barton, which nearly died of blood-poisoning last fall and began the current season a maiden, is a better horse than Sir Martin ever was. He is as tractable as a well trained setter, a splendid manager of weight, a willing galloper of the smoothest action imaginable, he carries his speed equally well on muddy and fast tracks.

In a season distinguished for the high quality of its three-year-olds, Sir Barton has met and conquered the best.

Few racing folk had heard of Sir Barton until the running of the Futurity stakes at Belmont Park, last fall. His name had appeared on a racing programme or so, but it had not figured in the winding list. He had been beaten at Aqueduct and Saratoga while his more precocious rivals, Dunboyne and Billy Kelly, Eternal, Hannibal, Sweep On, Terentia,

Elfin Queen and Lord Brighton were winning gold and distinction. About all that was known of him was that Commander Ross had paid a matter of $10,000 for him at Saratoga in August to the end that he might have a representative in the impending Futurity.

Commander Ross bought Sir Barton because his great little gelding Billy Kelly, the juvenile hero of the Saratoga meeting, did not happen to be eligible to start in the Futurity. On a couple of fast Saratoga trials Sir Barton looked like a youngster that might develop Futurity form.

H. G. Bedwell, the trainer who had handled the Ross thoroughbreds for a couple of seasons and was destined to make the stalwart Canadian the biggest money winner among American horsemen for 1918, with earnings of nearly, if not quite, $100,000 to his stable's credit, as he is certain to put him in that enviable position again this year, took Sir Barton and Billy Kelly and the other members of the Ross establishment to Havre de Grace after the finish of the Saratoga meeting. None of the sophisticated expected to see him about New York again before the spring of 1919. So when Bedwell arrived at Belmont Park on the eve of the running of the Futurity and made the sanguine prediction that the colt that beat Sir Barton in the Westchester Association's great produce race, which was to have a value of about $30,000, would take the winner's end of the purse, he was listened to with good natured incredulity. But folks laughed outright when Bedwell declared that Sir Barton could do anything that Billy Kelly could do, only a little better.

NOR was Sir Barton so very highly thought of after the finish of the Futurity, notwithstanding the horse that beat him won. Dunboyne conceded 10 pounds to him and trimmed him without difficulty. Purchase, after wheeling at the start and darting over to the inner. rail, righted himself and all but caught the Ross candidate in the last fifty yards.

After Sir Barton's desperate two weeks' struggle with blood-poisoning at Laurel Park in October, throughout which both Bedwell and his sportsmanlike employer actually sat up nights with him, everyone was convinced that he was done for as a racing proposition. The fireside talk last winter of the impending spring renewals of the $25,000 Preakness at Pimlico and the $20,000 derby at Churchill Downs was mainly of Billy Kelly and Eternal. It was the prospect of a renewal at Churchill Downs on the 10th of May in the most popular of American spring specials for three-year-olds, of a rivalry between Billy Kelly and Eternal that had had its origin in the closeness of the finish of the $30,000 John R. McLean Memorial Cup at Laurel Park, the juvenile championship event of 1918, which Eternal had won by a margin of about 18 inches, that invested the 45th renewal of the Kentucky Derby with an anticipatory interest no previous derby had enjoyed.

(Continued on page 94)

(Continued from page 60)

It was not until Sir Barton had beaten the accomplished Cudgel in a public trial at Havre de Grace in April that the skeptical horsemen began to take his derby and Preakness aspirations seriously.

"But wait," prophesied the partisans of Eternal, "until Eternal and Sir Barton meet on a fast track and under level weight and we shall see which is the better horse." Eternal's partisans saw in the Preakness renewal at Pimlico four days after the running of the derby, but what they saw was not what they had expected to see. Sir Barton shouldered scale weight with Eternal this time—126 pounds—on a track that was very nearly fast and beat him without half trying.

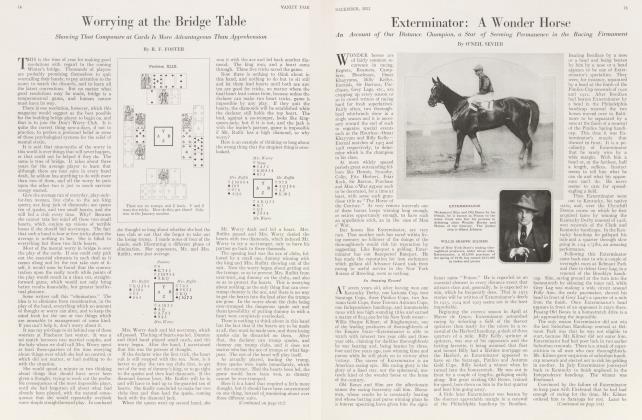

THAT was enough. When Sir Barton and Eternal met in the Withers stakes at Belmont Park, Sir Barton was an overwhelming favorite and he won as an overwhelming favorite should have won. When he met the gallant Sweep On in the Belmont, a race of one mile and three furlongs, which was run on a fast track, the first Sir Barton had had all spring, he was once more a topheavy favorite and once more he won as a topheavy favorite should have. Moreover, he covered one mile and three furlongs in 2:17 2/5ths, which time was faster than any other threeyear-old ever made in the running of a Belmont.

Sir Barton's time shaded Hourless' record of 1917 by two-fifths of a second. It would be difficult now to frame a race for three-year-olds or one that might bring Sir Barton in competition with the best of the older horses in which he would not be favorite. He is the new racing idol, and he deserves his fame.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now