Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSingers in French Opera

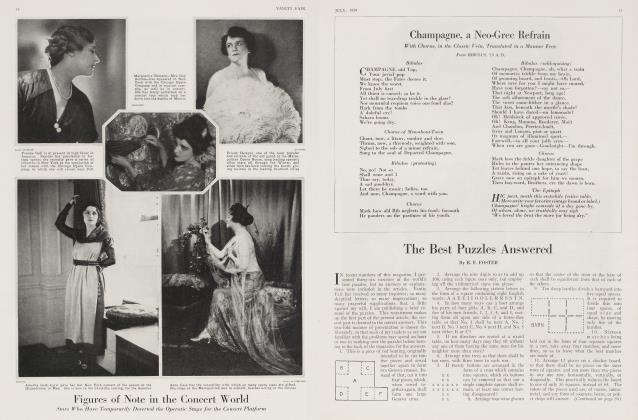

GERTRUDE MARION BARKA

Who Furthered the Cause of French Music in America

IN a recent number of Vanity Fair, there appeared an article called "Why Not More French Opera?" The question is a timely one,—why not, indeed?

At this time, when German opera can have no place in our American opera houses, productions of Italian works alone are not enough. If it were true that France had produced no grand operas of merit, the omission of French works from the program of the Metropolitan might pass without condemnation. But, with a wealth of French operatic masterpieces from which to choose, France should most assuredly receive the honor that is her due. Yet, during the past season, there have been but eight French operas produced at the Metropolitan. The advent of the Chicago Opera Company, it is true, added somewhat to the French influence; but there is still a chance for great improvement. Some of our greatest singers are at their best in the French operas.

The Wagnerian Revolution

THE art of singing has come to be so closely associated with the art of acting, in the last few years, that we forget how modern this theory is, unless we are students of Wagner. It was not till after the musical war, which Wagner instigated, that the French composers saw the wisdom of this Wagnerian revolution in opera, and proceeded to follow in his footsteps as best they could. It was the absurdities committed in operas, —the shepherd and shepherdess, about to sleep in the wood, commanding the birds to be quiet, and then singing at the tops of their voices; or the large, strong, healthy-looking ladies, dying of consumption or of starvation, in the last act,—that caused both composers and singers to ponder, with the happy result that has elevated the opera to its proper sphere. It is not enough that we hear an artist sing; before he can be considered a great artist, he must make us feel the character which he impersonates, that the subtle idea of the compbser may not be lost.

It has been said that a great singer is one who can move even the souls of those in the box seats.

Of all the great artists, only Patti and Melba were born singers. They alone did not require the wise guidance of a Garcia or of a Marchesi to place their voices aright. Mendelssohn summed up the secret of Jenny Lind's success in three words,—"Talent, study, enthusiasm." These three words comprise the lives of all the great singers; the greater the singer, the more arduous was the study and preparation.

There have been many noted singers in the last three generations (some of whom have never appeared in America), but they are best known for their German and Italian productions. However, French opera has never been slighted by our greatest artists.

Although Scalchi and Patti have more renown for their Italian roles, they are also remembered for their parts in "Faust." Scalchi, an Italian contralto, appeared with Patti, in New York. After a gala performance of Gounod's "Faust," at the old Academy of Music, in the early spring of 1884, Colonel Mapleson, the impresario, came before the curtain, holding Patti and Scalchi by the hands, and said to the immense audience, "As long as the French Opera has such singers as these, it cannot be supplanted."

Patti was indeed favored by the gods, and her life story reads like a fairy tale. At seven years old, when she first appeared in public, she sang her arias with the same embellishments she used at the height of her career. Although most of her singing was in Italian, it was she who made the "Jewel Song" from "Faust" famous, singing it in a way that has never been equalled in sweetness and clarity of tone.

Among the first singers who realized the necessity for combining singing and acting, if artistic perfection was to be attained, were Jenny Lind and Christine Nilsson, the two Swedish nightingales. It was said of Jenny Lind when she appeared as Alice in "Robert le Diable," that she was a new revelation in the domain of art. Her debut in London, in 1847, was a complete triumph for the prima donna. Queen Victoria, who became one of her warmest admirers, threw her a bouquet from the. royal box,—which was an incident unparalleled in the musical history of London.

Christine Nilsson was singing at the Lyrique Theatre in Paris at the age of twenty-one, and later had the distinction of being chosen by Thomas for the Ophelia in his "Hamlet." It was she who sang and acted Marguerite in "Faust," at the Metropolitan, with such remarkable ability that a madman in the audience thought her love words were meant for him, and caused her serious annoyance by his devotion.

One of the finest actresses of prima donnas was the lamented Hungarian Estelka Gerster, who, in 1886, lost her voice when her child was born. Gerster's Marguerite, for dramatic action, surpassed even that of Patti. She made Marguerite a human being of love, hope and despair; and she was young and beautiful enough to look the part. A critic of many years' standing in New York says of the two women, "I heard Patti when her voice was golden, and sounded like vocal velvet, but Gerster touched and moved me more."

Some Famous Singers

IT was left to France itself to produce the greatest Carmen, for no one has equalled Calve as the gypsy maid. This vivacious Frenchwoman brought new life into the field of opera, and her roles in French operas are superb. It is told of her that her tomb has been completed for several years; its principal features are two statues of herself, one as Ophelia and the other as Carmen. Although she achieved brilliant results in other French operas, it is in "Hamlet" and in "Carmen" that , she won a place in musical history as a creative interpreter without an equal.

The British Empire has produced several noted tenors and baritones, but only two prima donnas. One of these is Melba, the daughter of Australia. Melba's vocal organs, like those of Patti, were so built it seemed impossible for her to sing otherwise than beautifully. The trill, which alone would have made her famous, manifested itself in childhood, and attracted much attention even then. Although she is best loved for her Lucia, she distinguished herself in French opera as Ophelia, Marguerite, and Juliet; and her mad scene from "Hamlet" won the most flattering praise of the composer.

Mary Garden is the other prima donna that the British Empire can boast. She is Scotch by birth. If she had depended on her voice, alone, she would never have achieved the fame that is hers to-day; yet her dramatic ability is so remarkable that she has succeeded, in spite of her limited vocal powers. She has done more to make Massenet's "Thais," and his miracle play, "Le Jongleur de Notre Dame," famous than has any other one person

(Continued on page 102)

(Continued from page 100)

loyal Americans, we can be justly proud that our own United States has given four stars of the first magnitude to the operatic firmament. These prima donnas are the majestic Nordica; the Californian singer, Sybil Sanderson; the unassuming aristocrat, Emma Eames; and the dazzling, impulsive Geraldine Farrar.

Nordica shared with Lilli Lehmann the honor of being the greatest Wagnerian soprano the world has produced. But before she reached those frozen heights she had the distinction of studying "Faust" and "Hamlet" with the composers Gounod and Thomas, and of receiving homage in these roles that even the praise-loving Patti would have envied.

Nordica's life story is so full of interest and so truly American that we cannot but be proud that her own people received her so royally. Never will that audience forget the memorable night when Nordica was presented with the diamond tiara, which became as familiar to all as was her wonderful voice. It was the most triumphal occasion in her career, and was a tribute to genius such as few singers have received. Her untimely death in the South Pacific Island is as lamentable as it was unexpected.

Sybil Sanderson, the Californian soprano, did not meet with the success in America that she found in France. Massenet was jubilant over her interpretations of the roles in his operas, declaring that no one could sing them as could she. It was through Sybil Sanderson's hospitality that Mary Garden found a resting place in Paris, before her wings were ready for flying; and it was Miss Sanderson who secured for Miss Garden the minor part in "Louise," from which she jumped to sudden fame.

Great American Sopranos

EMMA EAMES happened to be bom in Shanghai, China, but her parents were loyal Americans, and her childhood was spent in this country. When she was studying in Paris, Gounod asked the husband of the famous Marchesi if his wife knew of a Juliet—he was looking for one. This was Miss Eames' opportunity. She sang the airs so successfully before Gounod that she was engaged for the opera company at once, and all Paris went mad over her. She had the good fortune to sing with the great Jean de Reszke, at her first performance, which added, naturally, to her success. Like Jenny Lind, she was best in roles that harmonized with her personal traits.

The last prima donna of our countrywomen is Geraldine Farrar. This brilliant girl has just begun her journey on the road of fame, for she is only thirtyfive. She had the great fortune of having the wonderful Wagnerian soprano, Lilli Lehmann, for her teacher. It is said that the teacher actually tied her pupil's hands behind her, so that she would learn to express emotions with her eyes and face, instead of by means of gestures; and it is to this training that Miss Farrar owes a large measure of her fame.

At the age of nineteen, she sang Marguerite in the Royal Opera in Berlin with such sensational success that often the police had to be called to preserve order, so great were the crowds. It is seldom that such youthful roles as those of Marguerite, Juliet, and Manon are taken by artists who have the training and the experience to sing and act them, yet are young and beautiful, for good measure. Naturally, the world was at her feet.

As Juliet, she is so like the fourteenyear-old heroine of Verona, that Gounod would have gone mad with happiness could he have beheld her in that role. Her Marguerite is different from that of

all other prima donnas who have appeared in "Faust." It is said that, at her New York debut in that opera, standing between Caruso and Scotti, with the big Caliapini in the background as Mephistopheles, she looked like a child; but her sublime acting was that of a wonderful woman. But perhaps the one of her roles most universally admired is her Madama Butterfly. She is so completely the Japanese heroine that even the Japanese wonder at her knowledge.

Because of her youth, Miss Farrar belongs to us, and our generation. She has the distinction of being the reigning prima donna this season at the Metropolitan, where German opera usually predominated. She receives the paltry salary of $1500 every time she sings.

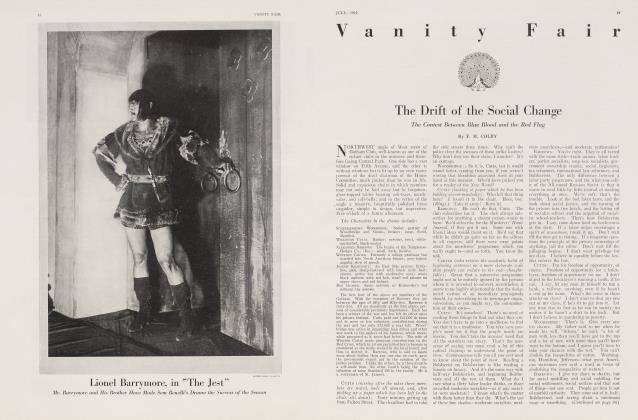

TN studying the men who have made French opera famous, the De Reszkes, Renaud, Scotti, and Caruso stand out most prominently. The most renowned of these is Jean De Reszke, for he has the distinction of being the greatest tenor of all time, and one of the finest singers the world has ever known. De Reszke is pronounced greater than Caruso because the range of his gifts is more extraordinary. He could sing not only the French and Italian operas, but the most difficult Wagnerian roles as well. No French tenor could equal him in "Carmen," "Faust," and "Romeo and Juliet" and his first distinction was won in Meyerbeer's "Les Huguenots." He was so marvelous an actor that by one word or gesture he could move an audience to tears. He received the highest salary any singer of his sex has ever commanded.

His brother Edouard was among the basses of his day what Jean was among tenors. He was as able an actor as singer, and his Mephistopheles in "Faust," and his Marcel in "Les Huguenots" could be equalled by no French singer.

The baritone Renaud, French by birth, has become so well known in French opera that he deserves an honorable place in its history. It is he who made the "Jongleur de Notre Dame" famous, together with Mary Garden: and much of the popularity of "Thais" is due to him. He has also won the hearts of the lovers of French opera by his masterly portrayal of Herod in Massenet's opera, "Mefistofele," in Berlioz's "Damnation of Faust," and "Les Contes d'Hoffman."

Antonio Scotti, the popular baritone, created the role of Scarpia, in the first American performance of "La Tosca," in 1901. He made his debut thirty years ago in Malta, and his career has been a long succession of triumphs. He has a particular gift for portraying singularly realistic villains.

The Many-Sided Caruso

CARUSO, the idol of the Metropolitan, needs no introduction. His popularity is unbounded, and his salary is fabulous. He has a magnificent voice that pours from his throat without the least apparent effort. He is the delight of the talking machine owners, for his voice, of all the artists, makes the best phonographic records. Were he to lose his remarkable voice, he could still earn his living, for he is a comedian of rare worth, and a cartoonist of ability.

It is certainly not out of place, in summing up the masculine opera singers of modern times, to include Lucien Muratore, the tenor of the Chicago Opera Company. His interpretation of various roles, through a long list of French operas from Leroux's masterpiece, "Le Chimineau," to Bizet's "Carmen," proves him a singer of great ability. As Don José, in the famous "Carmen," he made a great success in New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now