Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Mighty Hitters in Golf

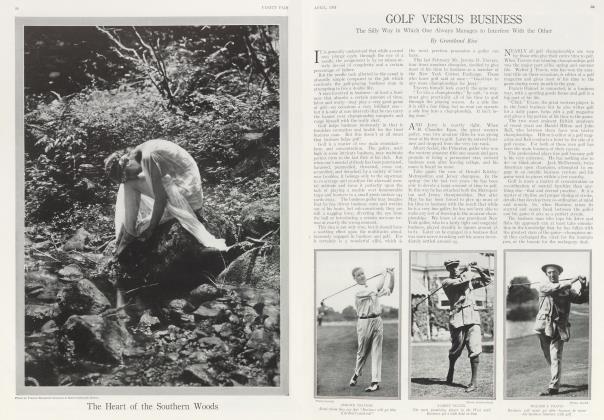

GRANTLAND RICE

Long Range Stars and Human Siege Guns Prove That Distance Lends Enchantment to the Golfers View

THE siege gun is always an interesting institution. Interesting in warfare and equally interesting when it arrives in human form to slash a baseball over the center field fence, or drive a golf ball over three hundred yards, carrying traps, pits, bunkers and ponds in its flight to the distant green.

Some years ago the badly moth-eaten idea got around that distance meant nothing in golf —that direction was the little golden-haired child of success, and that nothing but direction counted in compiling a winning score.

We have no intention of arising here to state that distance means more than direction. It doesn't. But it means more than it is supposed to mean, and in addition, the yearning to hit the ball a mile carries the greatest appeal of the game. But distance is something more than a mere lure to the golfer's soul. It is, for championship golf, a vital aid and an absolutely necessary ingredient.

A short while ago I was talking with James Scott Worthington, one of the best of the veteran English amateurs, regarding the importance of long range play. "I recall," he said, "a match I once played with Abe Mitchell, a mighty hitter, probably the longest of them all. In this match I never played better golf. I was straight to the pin all through the round. Mitchell on the other hand sliced and hooked on several occasions, wandering off into trouble. Yet in spite of this I was beaten 3 down and 2 to play, simply because his longer range gave him an immense advantage. I had outplayed him that day in steadiness. Yet, he won through his ability to get from 30 to 40 yards farther with his wooden clubs; to reach long holes in two where I needed three; to miss one shot and then catch up with me on his next."

The Longest Hitters

THE talk of every golf gathering is always full of discussions built around the longest drivers at the game.

"The high east winds which prevail in the locker room," as George Ade once put it, are frequently devoted to this phase of the game.

No one has yet established final proof as to the longest driver in American golf, but any number of candidates have been entered, from H. Chandler Egan on through Jesse Guilford, known as the Siege Gun.

H. Chandler Egan, the Harvard golfer who won the amateur championship way back in 1904 and 1905, was the first star amateur to leap to fame through his exceptional prowess in the long game. Egan had a wallop of rare repute. Blessed with strong hands, powerful wrists and forearms, he could tear into a golf ball with tremendous velocity.

The way this extra distance came to him is an interesting chunk of golf history. He had been only a fair hitter, as to range. And then, returning from college one summer, he was suddenly driving 30 to 40 yards beyond any competitor, east or west.

No one knew the answer until one day a few friends happened to see Egan out swinging a 16-pound hammer. He had taken up this track sport at Harvard and the development which followed not only increased his muscular equipment but added immensely to his snap and leverage. This training with the 16pound hammer undoubtedly made Chandler Egan the longest hitter of his day. This training also made -it possible for him to stalk into the rough, and tear the ball out from a heavy lie for almost unbelievable distances. He had both the power and the leverage, which, with the proper timing, are the three main factors in long distance play. Egan has dropped out from tournament golf but the echoes of his long-distance shots still resound where older golfers gather to talk of the game.

The Human Siege Gun

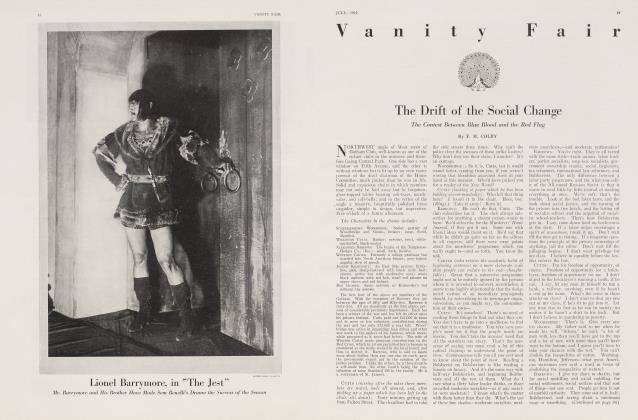

LL past records for long driving in America went to smash when Jesse Guilford appeared at Manchester, Vt., for the amateur chamoionship of 1914, held over the famous Ekwanok course.

Guilford was unknown then, both to the gallery and to his various competitors. He had been a New Hampshire farm boy, powerfully built, with a broad neck, heavy shoulders, deep chest and thick, strong wrists and forearms.

But he was destined to remain unknown for only a snort while. The course had been heavy with recent rains, killing all run to the ball for the first day or two, but this failed to bother Guilford at all. He had a swing that was a perfect circle, a back swing that sent the club head to his left heel and a follow through that left the circle complete. On the first hole at Ekwanok there is a brook, 300 yards from the tee, guarding the green. Guilford on one occasion carried this hazard, the ball dropping 8 yards beyond, where it was partially buried A carry of 308 yards is an extraordinary affair.

Later on, when Guilford stepped upon the tee to drive, crowds would desert other matches in order to see the husky young New Hampshire farmer give a display of his long distance wares, and they were seldom disappointed. He was frequently from 50 to 75 yards beyond his opponents, using a mashie for the second shot where his competitor had to use a full brassie to get up.

As the course began to dry out Guilford began to drive from 320 to 330 yards, most of which was carry.

In his match with Fred Herreshoff, Guilford came to the 12th hole for another supreme test. The fairway at this hole slopes out to a high crest where the plateau is 275 yards from the tee. Most long hitters were content to drive within 15 or 20 yards of the top and then poke a mashie to the green. None of them reached the top—until Guilford came along. The Siege Gun let fly with all the ammunition he had—which was a considerable amount. His resounding blow struck the top of the crest on a carry, bounded over for an incredible distance and left him a little chip shot for the flag.

A year later Guilford tamed down his swing to normal proportions, and while he is still a long driver he no longer obtains the amazing distances of his Ekwanok debut where, for a week, he made a fine golf course look extremely foolish. He was fully as accurate with the full, deep swing as he is to-day with the shortened stroke, but it may have been that he finally became bored at playing nothing but chips after a drive. Whatever the reason, those who yearn to see a golf ball travel over almost endless routes, miss the old circular wallop that used to turn the trick for him.

(Continued on page 80)

(Continued from page 57)

The Pole Vault Swing

IT is very likely that you never heard of the pole vault swing in golf. Robert A. Gardner, twice amateur champion, doesn't swing a golf club precisely as he handles a pole in the vaulting arena, but pole vaulting helped to make him one of the longest maulers of the game, for all of that. Gardner, who was captain of the Yale track team, once broke the pole vault record above 12 feet. This training added both to the power and the leverage of his shoulders and arms, and thereby enabled him to brandish a golf club as if it were a light malacca calling cane.

Long distance from the tee and extensive range with his irons were factors that helped to give Gardner his second championship at Detroit in 1915. This course was long and at times heavy, and where other golfers on many holes were short with two full shots, Gardner could get home with a drive and an iron. On one occasion, in a tight match, he topped his tee shot and then, from a fairly rough lie, reached the green with a full cleek shot that measured over 250 yards.

Many Advantages of Distance

LONG distance brings advantages in many ways. It enables the walloper to get home in two very often where shorter players are shy. More than that, the long walloper can frequently afford to miss his tee shot and still reach the green on his second where the normal player after a missed drive can never hope to get near the pin.

This ability to rise up and swat the ball also enables the longer hitter to use a safer club—to employ an iron for his second shot where his opponent must use a brassie—to have a mashie shot left where his rival may need a spoon or a cleek.

No, there is very little to the ancient theory that distance means nothing in golf-—that direction is everything. Direction is a most important factor. But without distance it won't get very far in this rapid age where there are too many golfers who have both aids working for them side by side.

A Few World's Records

WORLD'S long distance driving records abound in golf, but when it comes to authentic proof there is generally a hitch in the proceedings.

There are established records that go beyond 400 yards, but these have included a favoring wind, a frozen or a baked-out course and a tricky roll to the ball. The only records worth con-' sidering are those that deal with carry only. Golfers have driven half a mile on the ice, where the matter of making a record is nothing but the ability to find an ice field long enough to win with. But carry is another affair. In this respect the longest blow I know of was delivered by Abe Mitchell, the English professional, who carried a bunker 300 yards from the tee, by 17 yards, accurately measured. Some one may have beaten this mark, but if so he has modestly concealed his achievement. Or it may have been that he had a shrinking antagonism to being called a—shall we say?—liar.

Ted Ray and James Braid are two other long driving British players, but

neither of them quite gets the distance reached by Mitchell when the latter is really hitting the ball. In the way of both height and distance Ray has few equals. His trajectory is a lofty one, the ball soaring to immense altitudes but, in spite of this, dropping well beyond the range of most of those who depend on carry and run. Both Braid and Ray weigh over 200 pounds. Ray can get as far with a niblick shot as an average golfer can get with a full iron. In the way of iron play there are no players in America who can outrange waiter Hagen, the 1914 open champion. Hagen can get as far with an iron shot as long hitting professionals can get with wood, and this gives him a distinct advantage. He can tear into a close or heavy lie and reach the green 220 or 230 yards away, where few golfers could take the chance if there were any hazards to carry, or where they would need a full brassie shot to get on.

Another Long Player

A NOTHER of the longer players is Bobby Jones, the 17-year-old Atlanta star. Young Jones is well built but not husky in any sense of the word, compared to such men as Ray, Braid, Hagen or Guilford.

But he has strong hands, thick wrists and a remarkable ability to time his shot. His back swing is even and replete with rhythm. And from this start he tears into the ball with tremendous force, whipping the club head in with a crash.

In a recent match at Garden City, he drove into one bunker 310 yards from the tee and later, against a heavy head wind, played a 440-yard hole with a drive and a mashie where a drive and a brassie were the order of the day.

Not all of the mighty hitters are wellknown stars in the golfing realm. There is, by way of example, Dixie Flaeger of Chicago. Flaeger plays very little . tournament golf and he doesn't give enough time to the game to acquire the needed steadiness. But there are many who believe that he is the longest driver in America. Out West they credit him with outdriving Bob Gardner by 20 or 30 yards, and the man who can outhit Gardner by this margin must be a marvel of purest ray serene. Knowlten K. Ames of Chicago, to whom golf is both a study and a recreation in his spare moments, says that Flaeger can outrange either Chandler Egan or Bob Gardner in fact Mr. Ames is confident that Flaeger is the longest driver he has ever seen—a most prodigious propeller of a golf ball. There is one instance where he reached a 500-yard hole with a drive and a mashie where his three opponents in a four-ball match needed a drive, a brassie and a pitch to the green, and the three men were considered respectable hitters, at that.

And, while you hear very little about his ability in this respect, Gil Nichols doesn't very often play first after leaving the tee, no matter what type of player he faces. Gil has a long run to his drive, played with a slight, pull and a whip of the wrists that impart a jump and oll to the ball that are almost beyond explaining.

But, you may ask, is it better after all to get away long drives or to get down long putts?

That almost sounds like another story —a story to be treated in a later issue of this magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now