Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowNo Taxation Without Fermentation

Showing the Need of a Unifying Slogan

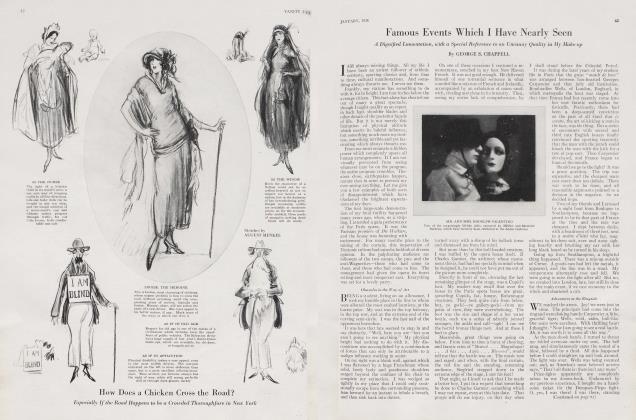

GEORGE S. CHAPPELL

DAME NATURE is a quaint old fowl with an acute sense of humor. She has a delightful way of completing a cycle without telling anyone about it, and then sitting back to enjoy the results. I imagine she must have grinned broadly when the scribes in charge of the Prohibition Amendment laid down their fountain pens and decided to call it a bill.

They were so satisfied with it. It was so complete,—so rock-ribbed, iron-bound, copperrivetted. It would hold water—and nothing else. But there was one clause in particular which undoubtedly caused Mother Nature to break into audible cackles. For, somewhere near the end of the indictment, the scribes had pointed out, in words as solemn as the wedding ceremony, that it should be a misdemeanor

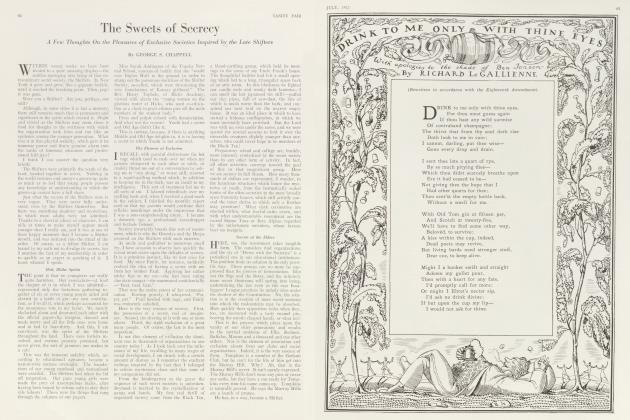

"to have or to hold, to transmit, give, sell, rent or force-upon another person any recipe, formula, specification, description, plan or drawing by means of which said other person, be it he, she, or it, should or might build, construct or brew a fermented mixture of potable quality containing more than 2.75% alcohol,—and so be it covenanted, until breath us do part."

or words to that effect.

IT was on the word "fermented" that the old lady cackled. I confess that I myself could take no such humorous view when I read the dreadful array of "don'ts" imposed by this measure. It seemed to slam the door in the face of hope. No recipes, no formulae? Not even a still-born high-ball? It was too awful! And vet L did nothing. Like thousands, ' millions of others I took the edict with a sort of a pathetic stoicism, inert, spineless, shameful. It was done; so be it. Nevertheless, deep within, protest grumbled,—discontent—dare I say it?—fermented. Others felt as I did,—and it needed only the tinder-spark to cause the explosion of a great, disrupting discontent which would complete the cycle to which I have mysteriously referred and which I will presently explain.

The cycle-closing operation began to function a few nights after the Wets had signed the Peace-Terms. I had been spending my evening, as had been my recent custom, at my favorite public-library tediously grinding out a Xmas story for Thirsts Magazine. But it was too hot . . . not the story,—but the weather . . . and after an hour's feeble struggle I gave up and started for home, dully wondering as I trudged up the Avenue, if something could not be done to relieve the painful aridity,—if we should all get together,—if . . . and then I stopped,—looked—and listened—for I heard, far above me,—singing,

"A slogan! A slogan! O, give us a slogan,— More potent than arrow or bludgeon or blowgun.

Just give us a slogan to plead for our cause And a fig for the Drys and their odious laws!"

THIS was the chorus, loudly, manfully sung to the tune of an old drinking-song which rang upon my ears. Like balm in Gilead the honey-ed words oozed into my flapping pores as I gazed eagerly to locate the source of harmony. Vainly I sought. About me was the usual picture of early-Prohibition gaiety. The dismal Avenue, the empty taxi-cabs, the glittering, dangerous soda fountains beckoning, calling, luring young men and maidens to syrupy destruction. But of the chorus I saw nothing.

Still it sounded as I went on, seeming to grow louder in an occasional fresh outburst of vocal sweetness. The Avenue was gradually filling with people; they came running, in twos and threes, even in ones, from the side-streets; windows were thrown open; human flies dotted the parapets against the velvety purple of night—and then, suddenly, in the dim obscurity of an overhanging cornice that happened to catch the gleam of a nearby arc light I glimpsed an unfamiliar detail and knew at once that I had solved the secret of the angel voice. It was a megaphone, cunningly inserted between two blobs of carving.

THERE are some things one knows for true the instant one perceives them—and the moment my eyes met the mouth of the megaphone I realized that I had made a startling discovery. The megaphone was nothing more nor less than one of those electrically controlled .devices for distributing sound which were used so effectively on Park Avenue during the Victory Loan to proclaim the glad tidings that Siam,—twins, elephant and everything—was ready to O. K. the League of Nations. But now this same device was being put to an even sublimer use. Now, through its myriad voices it was appealing to the great inarticulate heart of the world for a slogan, a device, a banner under which to group the scattered forces of good old joie-de-vivre.

"Just give us a slogan to plead for our cause, And a fig for the Drys, and their odious laws"

For the twentieth time the magnificent anthem sank to its solemn close and then fell sudden silence, a silence more effective than a salvo of artillery. The streets, now crowded, thrilled with tense expectancy. What next?

(Continued on page 108)

(Continued, from page 57)

"Attention!" said the megaphones. The word struck sharply on the throng. True to our military tradition every man and woman assumed the correct military position, quietly shuffling into squad formation, eyes right.

AND then a wonderful thing happened. The slogan was spoken! Aye! spoken by a hundred concealed voices far up and down the great thoroughfare, with a distinct clearness which was never dreamed of by the man who used to manipulate the talk-things in the Grand Central Station. Like one thunderous voice, the hundred spoke—

No TAXATION WITHOUT FERMENTATION !

Allow me to state right here that no such sight as that which followed has ever been seen on Fifth Avenue,—at least not within my memory. The words of that remarkable slogan fell like an absolute benediction on the parched and thirsting souls below. It reached into their inner beings and then welled forth again in a great crescendo that rose and fell like the sound of Niagara heard from North Tonawanda.

The parade was inevitable. It simply had to be. To the surging rhythm of their new battle-cry a tremendous majority of the great Metropolis swung into Central Park—entirely removing General Sherman from his pedestal in their resistless flow. There was the light of the Crusaders in their eyes. They were a people reunited, the lost found, the leaderless led—led -by an ideal, or rather the crystallization of it into a few plain words. All that they had suffered, all that they had felt and thought in their poor, dumb way was expressed in the slogan, a stirring echo of those sturdy men of Medford who dumped tea overboard and went back to their rum.

And was it too late for this vast horde to pluck victory from defeat? Never! From secret pockets, innerlinings, false-calves and other ingenious hiding places, too humorous to mention, the marchers produced strange bottles and containers filled with home-brewed exhilaration. Gaily they brandished them, pledging each other in the light of gray dawn and new found hope. And when they reached the Reservoir, ah! what a sight was there, my country-men ! A box-barrage of yeastcakes was laid down around all four sides of the placid pond,—wherein the water was soon a mass of churning foam. There they paused in exhausted fascination to watch the marvellous miracle, only dispersing as the morning sun gilded the spire of Senator Clark's fine example of frenzied architecture, dispersing to their work or to sleep after one grand, final repetition of their gorgeous slogan.

YOU all know what followed. The very next day we read in the paper that the ludicrous clause in the watertight amendment had been stricken out. It was gone, forgotten, non-est,—for all too plainly had the message sounded in the halls of Washington, shaking e'en the seats of the All-Dryest.

Thus another cycle was completed, to the old Earth-Mother's vast amusement, and the world entered again into the ancient ways of simple brews and homespun wassail. And after all, is it not for the best? Was it not getting a bit thick when one had to pay eighteen dollars for one's favorite vintage? Verily I think so. So much so, indeed, that I have heartily espoused the newold regime. I have gone into it with, enthusiasm plus scientific study. My recipe book is rapidly becoming a tome of portly proportions,—my home a laboratory of astonishingly complete equipment,—and the results are distinctly gratifying.

Inasmuch as I plan to publish the book in the Fall, it would be manifestly unwise to quote from it at this time, but it would be equally selfish not to give my friends at least a glimpse through the curtain of the joys beyond. I may say, therefore, that I have invented a morning-draught which I call "Big Ben" —I name all my creations just as Mr. Tappe does his—which has the potency of an alarm clock with none of its discordancy. The basis is vintage listerine (cuvee of 1918), of which I laid down a number of cases early in the year. A charming suggestion comes from an Uncle in Rome who tells me that for years the peasants on the Campagna have made wine by putting into four litres of varnish-remover, four kilometers of vermicelli. The starchy surface of the vermicelli entirely absorbs the varnish, leaving a clear winey liquid which, Uncle writes, reminds him of cooking-scotch, though rather stronger.

BUT why go on? The point is, all these things ferment. Leave it to Nature; she knows:—she has brought us back to simple ways and simple days.

And one more point. The great beauty of these domestic beverages is that the longer you leave them alone the better they are. I have several in my pantry that I think I shall leave forever.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now